Romance isn't as straightforward your simple meet cute anymore, at least according to May December and Saltburn. These critically acclaimed films leave audiences uncomfortable with their twisted themes and unsavory depictions of lust.

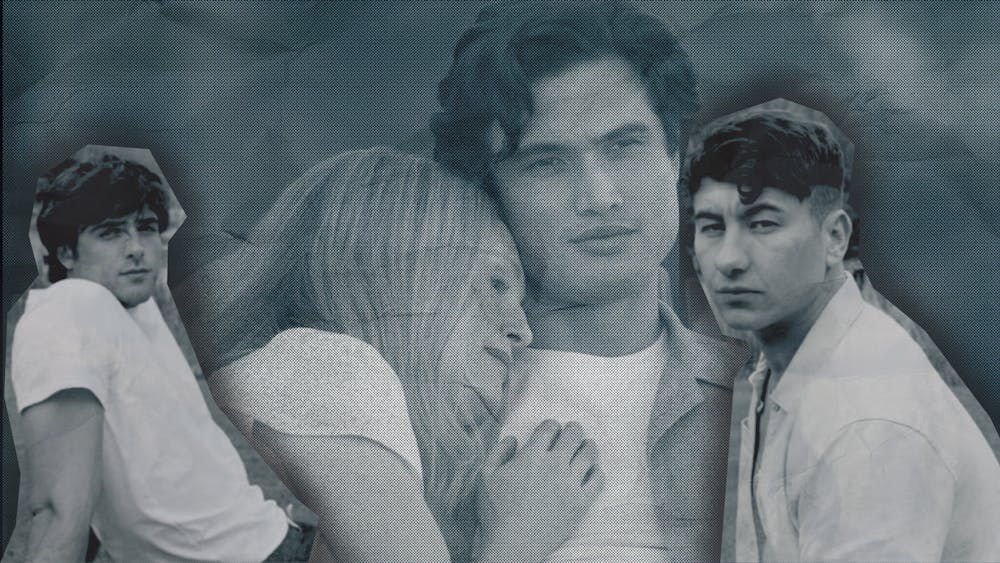

May December follows actress Elizabeth Berry (Natalie Portman) as she explores the complex relationship between Gracie (Julianne Moore) and Joe (Charles Melton) in preparation to play Gracie in a film. Years after Gracie and Joe covered tabloids for their illicit relationship, Elizabeth becomes enmeshed in Gracie and Joe’s life—eating dinner with their family, attending their kid’s graduation, going with Joe to work, and more. As she navigates their lives, she manipulates Joe romantically and inserts herself into intimate family events while pushing other family members out.

With every scene, May December succeeds in trapping the audience into accepting her behavior as a necessary act to complete her film and uncover the cryptic “truth” of Gracie and Joe’s relationship. In the end, it is revealed just how unnecessary all of the harm Elizabeth created was. The film is low budget with Elizabeth exploiting the child actor who plays Joe in an uncomfortably sexual scene. Just as the lines between morality and necessity are blurred in Gracie and Joe’s relationship, so too are the lines blurred between reality and acting in Elizabeth’s pseudo–method acting.

May December forces audiences to reckon just how easily they are willing to justify using another person within a relationship. Dramaticized depictions of unsavory and often immoral behaviors that arise in these twisted relationships on screen reflect our human failures in love and the ways in which we prioritize our own needs in relationships. For many young people today, undefined situationships are more commonplace. Ultimately, individuals find themselves in inadequate relationships where each person is unintentionally or intentionally using the other person to fulfill their own needs or desires.

During the film, Gracie defends her reasoning for giving her daughter a scale as a graduation gift. She says, “You try going through life without a scale and see how that goes.” The line is comedic and horrifying. The absurdity of the assertion makes the audience chuckle—yet, the conviction in which Gracie recites this line reveals the cultural implications of where women can derive power from. Carefully controlling weight and image to leverage opportunities requires the knowledge offered by the scale. In turn, the chuckle turns into a grimace.

Despite this being a portrayal of her relationship with her daughter, it reflects Gracie’s mindset in her romantic relationship with Joe. Appearance must be maintained and tightly controlled. Even the intimacy of a mother–daughter relationship is subjected to this outlook.

This theme of control is later echoed in the film’s climax when Joe, her husband, reckons with the former illicit circumstances of their relationship. In response, Gracie remains defensive that 23 years prior it was Joe’s fault that he, at age 13, seduced her, age 36, into sexual relations. In essence, regardless of his age, Gracie has decided that her viewing Joe as attractive trumps any consideration of morality, personality, and care.

We mock people’s appearances candidly in TikTok comments, collectively act to bring down people’s careers online by canceling, and swiftly dox those we disagree with. Similar to Gracie deflecting responsibility and evading the consequences of her actions, the ease in which we are able to behave immorally without consequences is unparalleled.

Saltburn also reveals how far false ideas of love and devotion can replace substantial human connection. The film presents Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan), a student at Oxford in pursuit of befriending the handsomely alluring Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi). Ultimately, the audience comes to learn nearly nothing of Felix’s personality, desires, and characteristics. Instead, they experience Oliver and Felix’s relationship through Oliver's distorted view of Felix as a mysterious, generous, and charming individual to be desired unendingly and to well–marketing extremes. All of Oliver’s social maneuvers and exploits are motivated primarily by Felix’s appearance—an obsession based both on Felix’s appearance of wealth and infallibility.

The audience is also enamored by Felix in spite of his purposeful lack of character. In a college roundtable interview, the director Emerald Fennell reveals, “Despite Oliver’s fascination with Felix, the idea of Felix is so seductive, but he himself is much, much less interesting than Oliver.”

Diffused lighting, languid shots of his body and sharp angles help to distract the audience from Felix’s lack of character until Oliver’s schemes are revealed at the end of the film. The film’s cinematography works to emphasize beauty as a seductive quality that can drive anyone to act in peculiar ways.

From May December to Saltburn, love, attraction, and appearances are all intertwined in a messy web of morality and emotion. These films allow audiences and creatives alike to explore these twisted ideas of love and obsession in a way that both allows us to confirm our existing ideas of morality but also threatens to normalize these unsavory behaviors. One thing remains true, that these films have exposed just how hard it is to maintain rationality while experiencing and observing the pursuit of love.