Art has been an act of resistance throughout the ongoing war in Gaza. As the war has martyred poets, scholars, and artists, there is an exigence to preserve Palestine’s rich cultural legacy of art and scholarship in order to bear testament to its existence. A rallying cry, seared in the public consciousness, came in Refaat Alareer’s poem “If I Must Die,” which gained prominent attention online after he was killed on December 7th by an Israeli airstrike. His haunting stanzas foretell a harrowing prophecy, professing “If I must die / you must live / to tell my story [...] If I must die / let it bring hope / let it be a tale.”

Thousands of miles away, students have been protesting the ongoing war in Gaza on college campuses across the country. These demonstrations come on the heels of Columbia University students’ protest that began on April 17, 2024. Across the country, encampments have been established at over 80 universities, demanding that their respective universities disclose their financial holdings, divest from Israeli corporations and institutions, and defend Palestinian students and their allies. Echoing similar demands, Penn’s own encampment began on Thursday, April 25, 2024.

Art, both as a creative medium and a vehicle for disseminating information, has taken on an indispensable role in these spaces. At Penn’s encampment site, organizers work with Penn students, faculties, and members of the wider Philadelphia community to collectively engage in poetry readings, create paintings and posters, hold sessions for singing and music, and curate on–site libraries.

The encampment hosts many intimate art workshops, such as a Bengali poetry reading in which a small group of ten people discussed the importance of poetry during the Indian and Bangladeshi Freedom Movement, amid authorities’ attempts to censor political communication. Lecture topics range from the Black Bottom to prison and carcerality.

Everything you see is a product of community effort. Art builds are encampment events where participants share space and supplies, passing around paint brushes and markers while cross–legged on College Green. Supplies are donated by Penn students, faculty, and allied Philadelphians, and artwork is created together as a means of solidarity. The art takes forms that disrupt the conventional—tarps and umbrellas become canvasses, with trees and clotheslines as their easels.

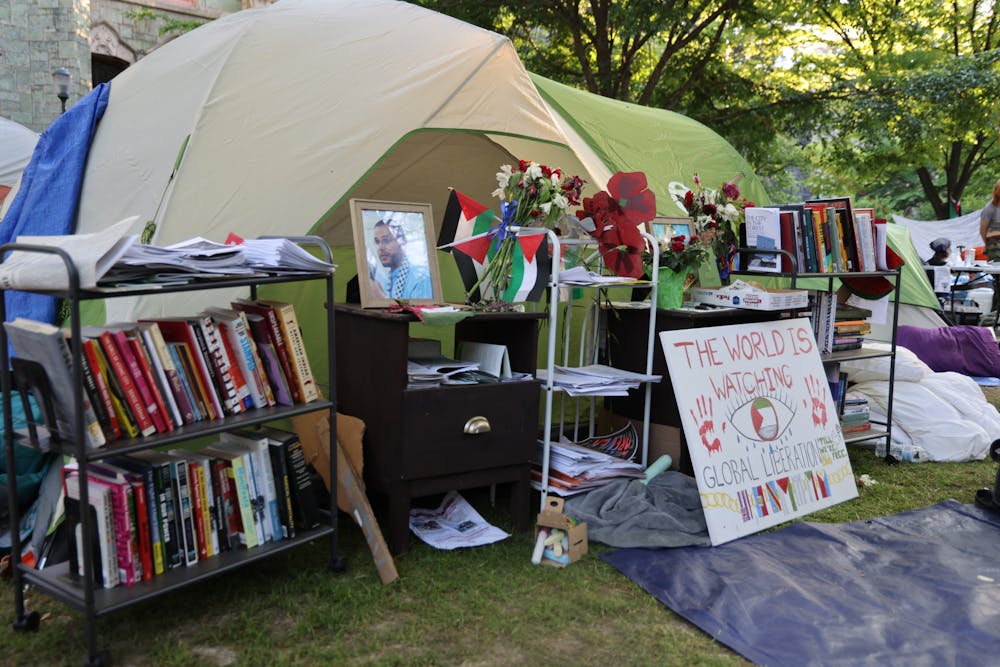

These displays are a physical manifestation of the sentiments of the encampment. For students who traverse Locust each day, to and from classes, the encampment isn’t just an interference of “business as usual.” Instead, the physical space it encompasses is itself a visual piece of art that can both disrupt and act as a gateway into the demands of the ongoing demonstration. Proclamations of solidarity, including “The world is watching: Global liberation ‘till we’re all free” are strewn in chalk and paint across the grass. Screen prints tied to tree trunks proclaim “Palestinians have the right to live in freedom.” Whether through their signs, their songs, or their stanzas, the encampment serves not only as a place of protest but as a place of learning.

Next to the Ben Franklin statue lies the Refaat Alareer Memorial Library, a community library originally intended for shared literature on Palestinian Liberation, by Palestinian authors. “We thought it was important to create, however small or big, a space for academic representation because there is a scholasticide going on,” an encampment organizer says. The library doesn’t fight the current of change. “It's really cool because people just come and put down zines or books that they just think are relevant,” they say. The intersectional collection of writings now includes those about AIDS activism, civil rights, and Marxism.

There’s a tricky line for protesters to toe; there are times that art can be a disservice if it detracts from or blurs the purpose of the encampment. Art is a means to an end, not the end goal in itself.

“We're here for a reason. We're here because there's a genocide going on,” the encampment organizer continues. “So there are moments where we're like, does it make sense to just start dancing, to start playing music? And people, even myself, have wrestled with that.”

In contrast to the liveliness of dance and song, reading the names of Palestinian martyrs requires absolute silence. Hence, in addition to uplifting morale and generating hope, art at the encampment functions as a powerful conveyor of personal experience and introspection in times of crisis. In essence, art promotes a dialectical process of change. “If the changes are happening—which they inevitably do—you have some friction […] and the friction cites discomfort, confrontation, reflection. That’s not a bad thing,” the organizer says.

In some sense, there will never be a “right” way of portraying trauma with art. The students and outside activists have been constantly searching for a way to connect with each other through art but also to stay grounded in their mission. Balancing the inherent joy of visual and performance art—the politics of hope—and art’s capability to invoke reflection through displacement and even discomfort continues to be a focal point.

Organizing is an art form in itself—the careful planning, in conjunction with the spontaneous defense against opposition, necessitates creativity.

The creation of art is also a radical archival act, particularly in a war where 120+ journalists and media workers have been killed on the ground in Gaza, while journalists and legal observers on college campuses have been shut out of university grounds. The tremendous burden of recording both atrocities of war abroad and blatant First Amendment violations on home soil has thus fallen on those under siege. To chronicle these events as they unfold is in itself an act of resistance, when those wielding the force of institutional power seek to stifle these real-time records, controlling a narrative as it unfolds.

In an effort to chronicle the mounting casualties of war, in January Penn Faculty for Justice in Palestine conducted a die–in to call attention to Penn’s “inaction [...] towards the Palestinian community and the racist, hate speech directed towards faculty, staff, and students calling for Palestinian justice.” In a demonstration, protestors laid down on the steps of College Hall in a simulation of “death” and unfurled a lengthy scroll, detailing nearly 7,000 names of Palestinians who had been killed since October 7, 2023.

Amidst a barrage of newsreels describing mounting civilian casualties, these demonstrations are a reminder that protest isn’t supposed to be passive or convenient. Protest is—by its very nature—intended to disrupt and remind us not to turn a blind eye or turn off the channel. Demonstrations like the die–in act to disrupt daily life as well as serve as an entry to an accumulating archive, detailing the atrocities of war as they unfold. Without these entries, it is far too easy for the Western world, its leaders, and its constituents to remain entrenched in the status quo and allow history to repeat itself.

Art created during the encampment also serves as a material testament to dialectical changes throughout the movement. “Discussions and the encampment can kind of change organically and fluidly throughout our time here,” the encampment organizer says. Art created throughout these processes, in turn, serves as a time marker to document these changes in an empathic and humane manner, chronicling significant discussions and archiving personal memories. From a practical standpoint, tangible manifestations that delineate the growth of the protest is necessary when power in numbers may be the only weapon organizers wield.

“You might forget about why you're here,” the organizer says, “I've seen so many examples in Gaza, refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon they're saying ‘Thank you Columbia.’ ‘Thank you Penn students.’” Instead of discrediting the collective efforts of protesters around the world, organizers remind us of their true aims: to remain vigilant about Penn’s complicity in waging war overseas.

Penn’s encampment is a forceful public exhibition, in which Penn students and community members must reckon with the ugliness of war, through art. The adornments of the encampment represent the intersection between art and protest. Though their intent can be skewed by outside sources, the organizers’ messaging is clear through their art, which is purposefully loud and demanding of onlookers’ attention. Against all odds, archival activism continues to flourish with time and is a striking reminder of protester’s efforts.