When the Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts (PIFA) begins next month, 1,500 artists will stage plays, perform acrobatics and even install an 81–foot replica of the Eiffel Tower to replicate Paris’ vibrant creative scene between 1910 and 1920. Those who visit the exhibit, “Paris Through the Window: Marc Chagall and his Circle,” under the pretense that it should be a blockbuster are likely to leave disappointed. The show is on view at the Perelman building and comprised of roughly 70 paintings, sculptures and works on paper created by Chagall and his emigre contemporaries.

However, Michael Taylor (the exhibition’s organizer and the PMA’s curator of Modern Art) compensates for “Paris Through the Window’s” lack of volume with quality. Beyond the expectation and noise of the PMA’s main building, Taylor is able to step into the modernists’ smoky cafe culture and provide visitors with a privileged understanding of Chagall’s artistic growth while living in the city of light.

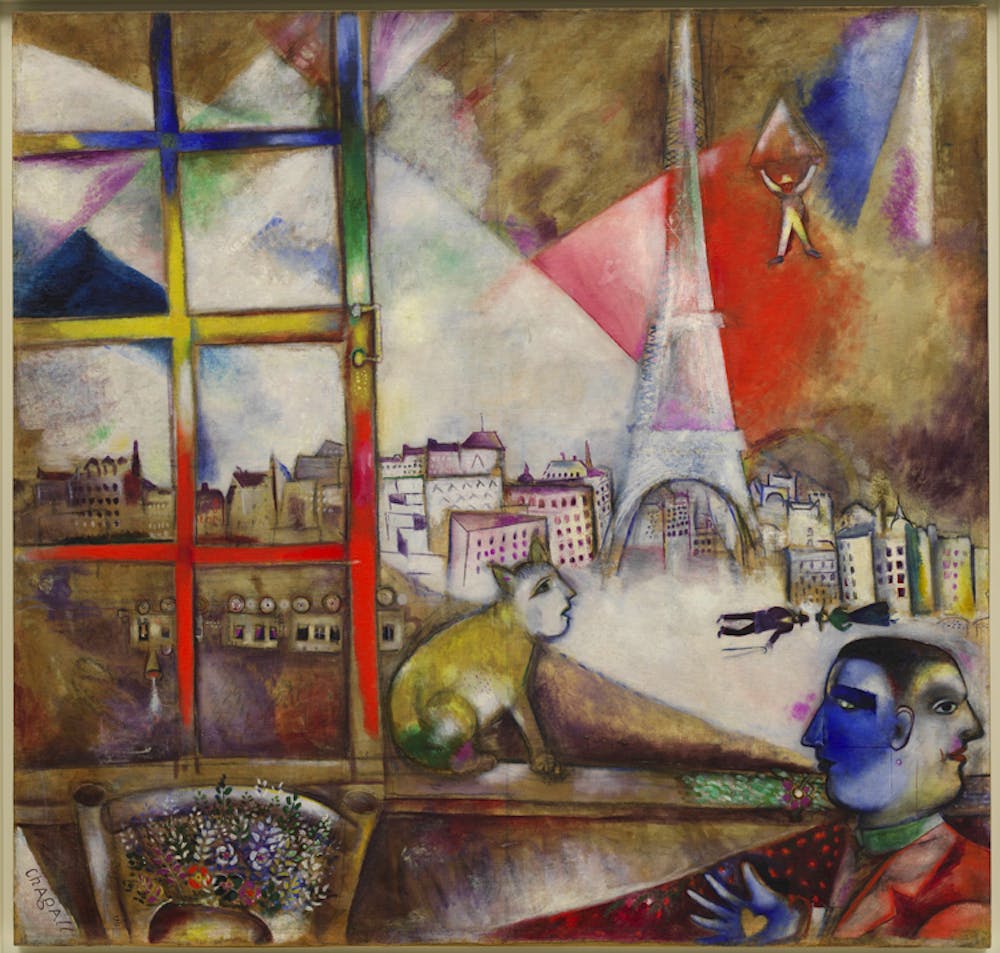

The exhibition’s first gallery assumes the difficult task of debunking self–generated myths concerning the Jewish painter’s artistic beginnings. With details of his early life in Russia obscured by the Iron Curtain, Chagall’s claims of singular genius went largely uncontested until his death in 1985. One can interpret the man parachuting off of the Eiffel Tower in the show’s namesake painting, Paris through the Window (1913), as a self-aggrandizing symbol of the artist landing fully formed and confident in the frenetic city below.

The intimate exhibition space draws a neat parallel to la Ruche, the small artists’ enclave where Chagall perfected his style in the early 1900s. Unlike those living in the more infamous Montmartre, the artists at La Ruche were united by their shared eastern European backgrounds rather than a collective visual style.

It was proximity to luminaries such as Archipenko, Lipchitz, Soutine and the lesser–known Moïse Kogan that helped Chagall create his much beloved faux–naïve style. The artist’s merger of innovative western painting technique and primitive Russian themes is clarified by the inclusion of mentor Leon Bakst’s folkish costume and set designs for the great Ballet Russes.

Chagall is a great master of visual incident, leaving surrealist figures, ambiguous religious symbolism and verbal puns (listen to Taylor’s description of Oh God (1919) on your cell phone) scattered throughout his saturated canvases.

The show is organized chronologically to include works from Chagall’s early years in Paris and state work in Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution. By strategically truncating the show at World War II, Taylor manages to leave visitors with a revised perception of Chagall as an emblazoned modernist, not the purveyor of twee Judaica he would become.

Paris Through the Window: Marc Chagall and His Circle Now through 7/10 Free with museum admission Philadelphia Museum of Art, Perelman Building (215) 763–8100 philamuseum.org