Zoe turns the corner on 36th and Walnut, where she pretends to window shop outside of Ann Taylor Loft, though she is really stealing glances at the passerby in the reflection. She then slightly lowers her Ray–Ban Wayfarers and turns around, facing the Penn Bookstore and Cosi across the street, scanning for anyone who might recognize her. Once Zoe reassures herself that she is undetected, she enters through the narrow doorway of the Counseling and Psychological Service (CAPS) building, proceeds to show her Penn ID to the security guard and takes the elevator to the second floor, all the while nervously tapping her foot.

“We think of ourselves as academic support, like a learning resource center or academic advising. Although we can treat mental illness, we’re really very interested in helping you do better in school. We don’t see ourselves as a medical clinic or treatment facility,” says Dr. Bill Alexander, Director of Counseling and Psychological Services. Dr. Alexander explains that less than 20% of students who visit CAPS are treated for serious mental illness. The majority of students who seek out CAPS “come for ordinary, developmental and age–appropriate issues: relationships, homesickness, schoolwork and other traditional college problems.”

It is likely no surprise then, that Dr. Alexander cites November, March and April as the busiest months at CAPS, when students are in the throes of midterm and finals seasons. He also notes that the emphasis on counseling probably explains why CAPS sees significantly more seniors coming through its doors than freshmen. From pre–major and peer advising to intimate contact with RAs, “freshmen are already bombarded with counseling and advising.”

Zoe walks toward the receptionist’s desk to check in, scribbles her name illegibly on the sign–in sheet and sits in a chair in the waiting room. She slowly removes her sunglasses and surveys the room. Whether intentional or fortuitous, the ill–lit waiting room casts a shadow over its patients and cloaks them in anonymity. However, this obscurity comes at a cost. From the bleak walls to the sterile environment encased within them, the climate at CAPS can be described in a word: gloomy.

Because of the sensitive and personal nature of CAPS, confidentiality is taken very seriously. Although funded by Penn, CAPS operates independently of the school and its many affiliates, and maintains its own separate contact database. In an effort to broaden access and make it easy to preserve confidentiality, “there’s no clinical fee, there’s nothing on your bursar and your insurance doesn’t get billed — so it’s completely free.”

Just as before every other appointment, Zoe fills out a survey that is designed to gauge her current mood. She rushes through the questionnaire quickly but carefully, so as not to sound off any alarms of neuroticism or psychological instability. This reminds her of the 15–minute phone interview she had with Daniel (whose name has been changed for anonymity) when she made her first appointment at CAPS. Daniel, a triage counselor, inquired about Zoe’s motivation for scheduling a visit. “How do you feel about your schoolwork?” “Are you experiencing any difficulties with your friendships?” The questions were benign, resembling a conversation she might have with her mom. Zoe felt at ease until the disembodied voice asked her whether she had any self–destructive thoughts or considered harming herself. She replied no. Though she understands the importance of the question, she can’t help but feel frustrated at the idea that her run–of–the–mill problems might be conflated with psychological ones.

According to Dr. Alexander, anxiety and symptoms of depressed mood caused by situational and individual circumstances are actually the main reasons that students reach out to CAPS, followed by Attention Deficit Disorder — “we get a lot of requests for that.” Dr. Alexander realizes that many students in the larger Penn community usually perceive eating disorders, alcoholism and mental breakdowns as the most common problems treated by CAPS. “It’s not the biggest thing going,” he says. “It’s just very visible. But it’s still overshadowed by the students who come in for ordinary stuff.”

Nevertheless, eating disorders and alcoholism are “something that comes up, and it’s usually mixed with something else like anxiety or stress. For some students, alcohol is a way to solve a problem, to cope.” In general, Dr. Alexander notes that Penn students don’t seek help for body image or alcohol concerns until these issues begin to impact their health. Dr. Alexander says “the culture at Penn” fosters an environment in which “you can easily blend in. You don’t look very different. And it is true, you can drink fairly heavily, and you’re not gonna stick out” — the same holds true for eating disorders.

After an hour of counseling, Zoe leaves the office of Judith, her therapist (name changed for anonymity). “See you next week, Judith,” she says. Zoe and her therapist have been on a first–name basis ever since her first visit to CAPS freshman year. She’s grateful that Daniel paired her with Judith, whose expertise and methodology truly is the best match for Zoe’s needs. Not everyone is so lucky. Zoe’s heard stories about students who never find a therapist that’s a good fit; they become discouraged and never return. But even when months pass between their sessions, Zoe continues to schedule her appointments at CAPS with Judith. And with no limit on the number of times she can visit, Zoe intends to continue seeing Judith until graduation — and e–mailing with her thereafter.

Right now, the main obstacle that faces CAPS is understaffing. The staff at CAPS consists of therapists ranging from pre–doctoral and post–doctoral psychology students to social workers and psychiatric nurses, resulting in what Dr. Alexander refers to as an “eclectic point of view,” one that cultivates all of these different backgrounds and adheres to no single methodology or school of thought. Unfortunately, the volume of students currently seeking help far exceeds the number of staff members available, making the wait between scheduling an appointment and seeing a specialist relatively long. Dr. Alexander explains that this is a problem that Penn is currently addressing. He expresses his satisfaction in seeing how much the services have grown in the last decade. In the future, Dr. Alexander hopes to expand the facilities and add more clinicians. Next year, CAPS is organizing a new program targeted specifically at international students, “who are underserved by CAPS now.”

Zoe is exiting the elevator when she runs into Amanda, a friend from class (her name has been changed). Her cheeks begin to blush as she gives a subtle nod and attempts to avoid eye contact. But Amanda bites. “How was your appointment?” Zoe does not know how to respond; she musters a sheepish mumble of affirmation. Amanda does not pry. Instead, she carries on to the second floor, comfortably and unabashedly.

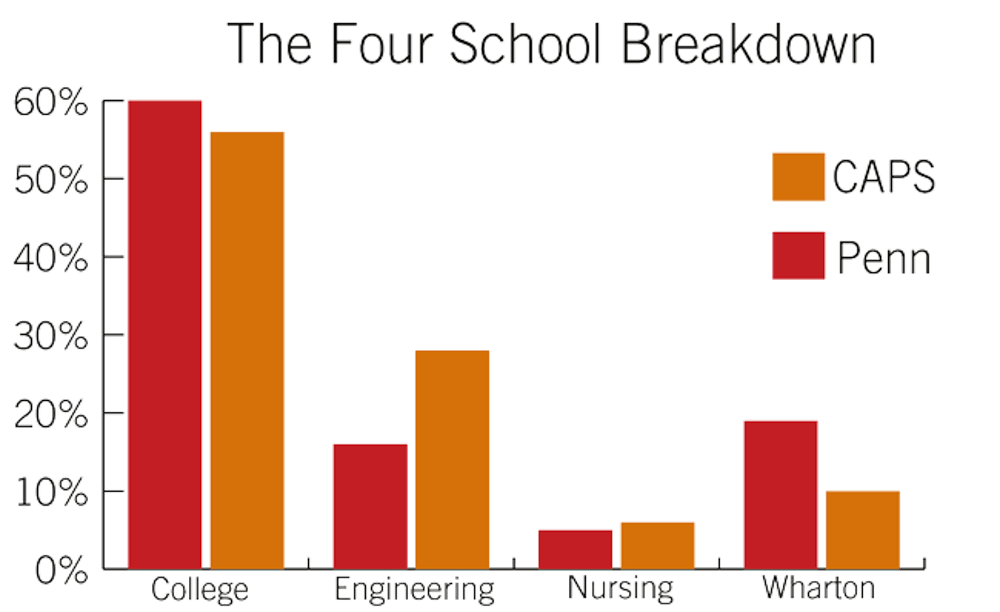

Despite its accessibility and emphasis on counseling, CAPS still struggles with the stigma surrounding its services. According to Dr. Alexander, only about 13% of the undergraduate and graduate student bodies uses CAPS services, as compared to 16–18% at other Ivies. In an effort to reach out to the Penn community, CAPS has an aptly–named Associate Director of Outreach. Through constant speaking engagements, this director serves as a liaison and consultant to academic departments, athletic teams, Greek organizations and student groups. Dr. Alexander attributes much of CAPS's progress to the “increased number of student–initiated mental health advocacy groups." He says that CAPS is “slowly chipping away at the stigma."

-------

Anthony Khaykin and Sandra Rubinchik are co–editors of Street's Lowbrow section. They are both juniors in the College from Brooklyn, New York. Anthony is a PPE major and Sandra studies English with a concentration in Creative Writing.