Name and Year: Olivia Rutigliano, Class of 2014 Hometown: New York, New York Major: English and Cinema Studies Twitter: @oliviarutiglian

Street: What brought you to the field of fashion design? How did you get started? Olivia Rutigliano: A 7th grade home–ec class brought me to the field of fashion design. I loved making those dinky throw pillows with the sewing machines so much that I was given some extra costumes to sew for the elementary school play. When I came to college I began to make handbags and dresses. The first dress was constructed from bubble wrap and duct tape – when I went as “the complete history Academy Awards” (my favorite thing) for Halloween, my freshman year. The dress, itself, was cut from bubble wrap (my friends and I popped the bubbles first), and printed on it, between a layer of duct tape coating the bubble wrap and a layer of a clear plastic, were the posters of every Best Picture winner since the ceremony’s inception. The zipper broke at the last minute, so my roommate had to tape me in, corset–style. I couldn’t breathe, but it was still fun.

Since then, I’ve made dresses from lots of different materials (including real fabric). This year, I am one of the Andrew W. Mellon Undergraduate Fellows in the Humanities with the Penn Humanities Forum, and one of the College House Reserch Fellows with the Penn Previews Research Symposium–and my research for both of these positions involves analyzing Shakespearian costumes throughout history. I’m writing a thesis on the changing culture of costuming Shakespearian heroines and then making six dresses that correspond to the characters and time periods I’m studying. It’s really exciting.

Street: Do you have any favorite designers? From where do you draw your inspiration? OR: I like fashion mostly because it is a form of practical creativity, but I prefer period costuming over fashion, because it is method, or subjective, fashion. I have an aesthetic responsibility to a character that can be fulfilled by not only researching the specific interpretation of the characters in the text but the historical or temporal period being represented.

My favorite designers sort of break the fashion mold and approach a highly creative or theatrical realm–and combine fashion with other artistic or scientific schools of thought. I greatly admire the intellectual curiosity and the historical and mythological understanding behind the designs of Alexander McQueen. I love the designs of the Italian Designer Roberto Capucci, who turned dresses into polychromatic, geometric sculptures. I also admire the French artist Isabelle de Borchegrave, who constructed elaborate period costumes predominately out of paper. I love the costume creations of both Colleen Atwood and Sandy Powell–each designer manages to dominate her respective projects with a highly specific, uniform, dazzling overall aesthetic, merging history with a kind of cool modernity. Oh! Bernard Newman’s elaborate gown designs for Ginger Rodgers’ musicals are unreal. And I grew up loving Adrian’s larger–than–life designs for The Wizard of Oz…There are more (so many) but I’m going to stop now.

Street: Walk us through your creative process. Does medium or budget tend to dictate the nature of your work? OR: The creative process, as well as the original vision, really depends on the nature of the project. If I’m making clothes for a show, the budget is an enormous factor. I’ll sit down with a director, hand over my sketches, and not only discuss ways I can make certain garments out of inexpensive (to the point of recycled) materials, but also explain the high quality items I will need to construct the more elaborate designs. There’s usually been one item in a show that gets the largest individual budget (i.e Titania’s dress, Cleopatra’s dress), and also the most detail and attention.

However, if it’s a personal project, I usually try to figure out how to make elaborate clothes out of random materials. I’ll have a general budget in mind, but since I’m just messing around, I can’t give myself economic amnesty. Which is why the dresses I make for fun are made out of tissue paper. And crayons. If I’m designing for my research project, though, I have a much more elaborate budget for each dress. In these cases, I do get to use extraordinary supplies, because all the dresses must be completely perfect and professional.

Street: Duct tape and wax dresses, huh? Tell us more about working with such unconventional materials. OR: Oh, it’s fun. Each ridiculous creative venture is like it’s own frontier. I think it’s genetic. My grandfather also enjoyed taking ordinary materials and turning them into works of art, but he was much better at it than I am. I make things out of duct tape or papier–mâché all time but melting and shaving a dress from wax (crayon wax) was the strangest, most fun thing I’ve done. Wax is really hard to get out of things, I discovered. Especially floor. But it was still awesome. There are lots of others, too. One dress was made dress from thick, gilded paper, one was made from plastic bags I ironed together to make a sort of thick fabric, one was made from tissue paper and cellophane, a couple were made from duct tape. I think the rest were more normal, and therefore made of fabric. Each time I do make a crazy, and potentially, um, dangerous, dress, I do lots and lots of research and only make them in certain areas, with certain materials, under certain conditions. Please do not try this stuff at home…

Street: You design costumes for the Underground Shakespeare Company. What do you find most appealing about Shakespearean fashion? OR: There are few formal stage directions in Shakespeare and even fewer indications of characters’ outfits. We know very little about what actors wore on stage in Shakespeare’s time, so, modern productions really have no choice but to take certain liberties with aesthetics. This can be good or bad. Restaging Shakespeare in unexpected times or places can really stretch the suspension of disbelief (Leo, if you are wearing a Hawaiian shirt, why are you speaking in iambic pentameter?), but it can also open up new insights into character and culture. I love the complicated beauty of Elizabethan costumes, but I also like being able to interpret a costume based on a certain interpretation of the character that might not come through in traditional dress. How much the costumes make sense, I think, depends on how well the director restages the play. I don’t mind experimenting with creatively re-staging Shakespeare, but I have my limits. Remember “Macbeth in Space” from Jimmy Neutron? Ahem.

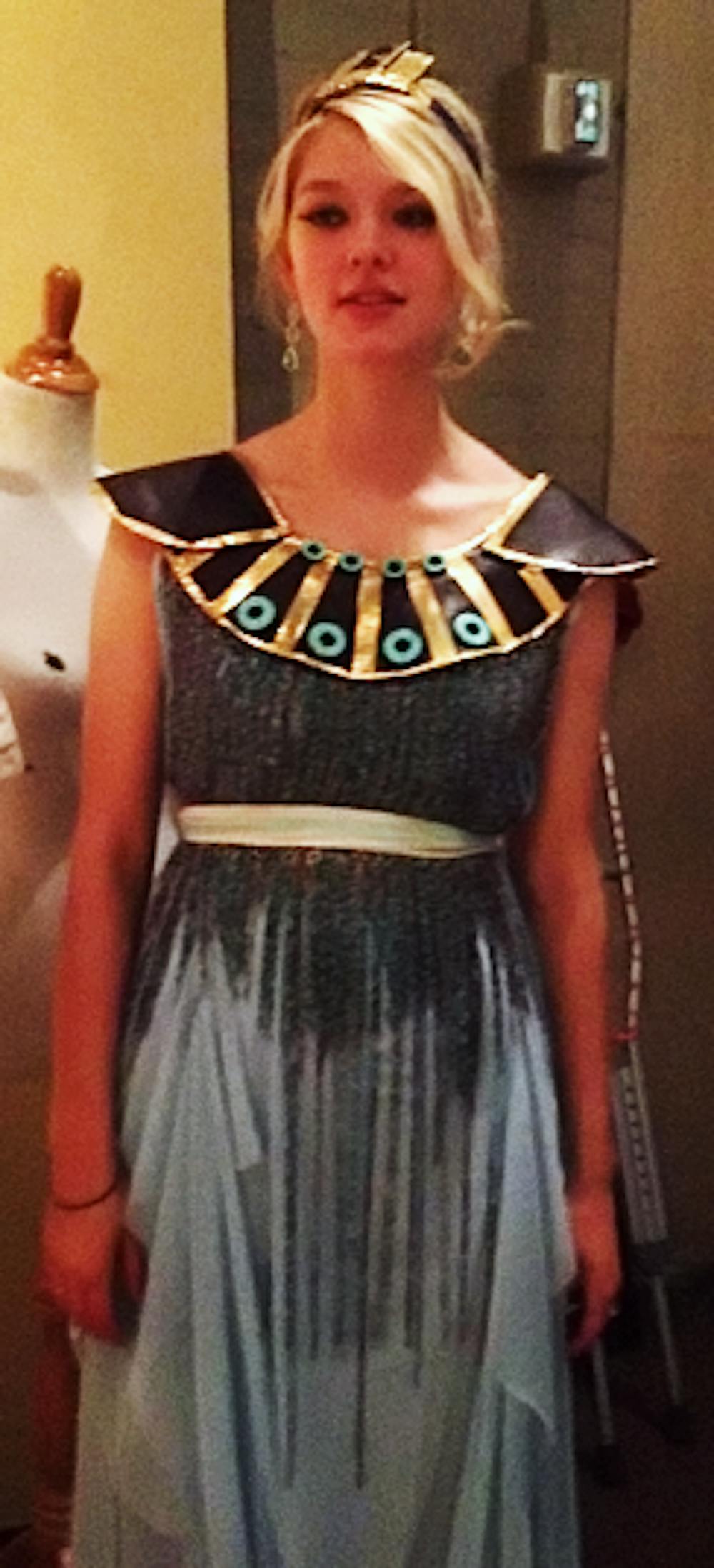

Street: How long would a piece like your Cleopatra costume take? OR: My Cleopatra costume is a terrible example of my normal production rate. It was for a USC/Philly Fringe production called “Antony and Cleopatra: Infinite Lives” by J. Michael DeAngelis and Pete Barry, staged in the Egyptian Wing of the Penn Museum. I had to make about fifteen costumes (classical Egyptian, Roman soldier, etc) and assemble about ten to fifteen other contemporary ones in nine days. Cleopatra’s dress, made from blue mesh with a beaded bodice and inset turquoise stones, was constructed in four days, in my dorm room (where I have a sewing machine and a dress form). I paused working on it only to go to class or work and do homework, and I hardly slept.

And things still went wrong! I had bought pre–strung reams of beads for the bodice, with the intention of simply stitching them to the fabric, but I accidentally broke all of the strings. So for three days, on and off, I had a sweatshop running in my dorm – friends came in and helped string the beads back on thread. Everyone was sitting, hunched over their work in the dimly–lit room, listening to Queen (for energy), weaving needles and thread through the piles of tiny beads. It was like a party, but one where all the guests were on–the–job factory workers.

So, yes. Cleopatra’s dress should probably have taken 3-4 weeks, but it took 30 hours (of hard–core labor). It was a fluke, a miracle. Without the help of all my friends (also Freddie Mercury), it wouldn’t have been done in time.

Street: Where do you see your design career taking you in the future? Have you considered experimenting with any modes of expression? OR: Believe it or not, I came to Penn with the intention of continuing on to grad school and eventually becoming a film professor. I still want to be a film professor. I’m really interested in the concept of adaptations, particularly the relationship between Shakespeare and film. In high school, I took classes at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, and my weird childhood dream of being a college professor (one I’ve had since second grade) was validated then and there.

My love for making costumes is a relatively new branch of my general, lifelong love for making things, so I’m not sure which passion – academia or creativity – will win out. I really hope I’ll find a way to do both.