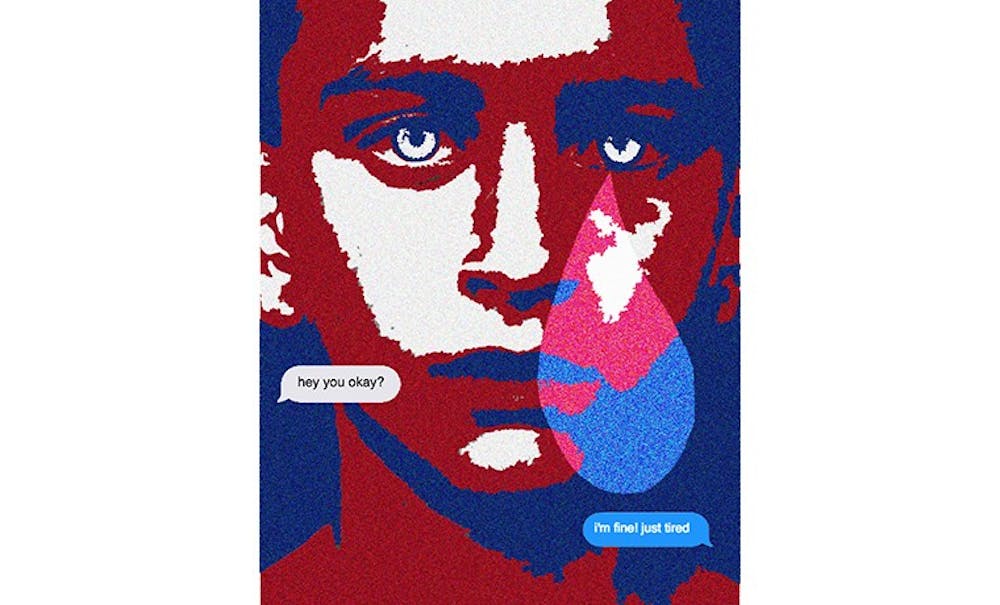

I know one thing for sure: I do not know what Penn Face is supposed to be. I have a hunch about something else: nobody else really does either.

* * *

My first therapy session as an adult was weird. I couldn’t sleep the night before, mired in a depression that no amount of Bruce Springsteen could shake off. I had stress dreams of my childhood therapy sessions, and those stray memories were all I had to inform me of the session to come. This was nothing like my childhood sessions. This went well.

My second therapy session as an adult, though, was tough. My therapist identified a problem: I found ways to distract myself to ignore depression instead of dealing with it. I took up crafts, I made sure to attend every club meeting I could, I took on some extra hours at work, all so that I wouldn’t be idle, alone with my thoughts. That’s the most important thing I would eventually learn in therapy: how to stop distracting myself, and take steps to safely deal with my issues.

After the session, I didn’t feel ready to go back to campus, so I ducked into my favorite deli to eat a soup and sandwich and decompress. I eventually headed back, wondering how I was going to explain to friends where I was. Eventually this would become a ritual: go to therapy, walk across the street for deli, play Jeopardy with the waitress and an assortment of old Jews who wished I was their grandson, tweet a picture of my food, lie about where I had been. It would be months before I felt comfortable telling people about therapy.

* * *

I came across the term “Penn Face” for the first time in the New York Times over the summer. The paper defines it as, “the practice of acting happy and self-assured even when sad or stressed.” The article asserted that the term is “widely employed,” but a quick Google search showed me that the only real use of Penn Face came from a (probably) poorly attended panel discussion in McClelland. I think it’s fair to say that “Penn Face” only recently became a thing.

Yet despite its recent origin, it’s become quite a big thing. In their open letter to Amy Gutmann, the Hamlett-Reed Mental Health Initiative suggested that, “a silent majority of students feel isolated, stressed and depressed. With the ‘Penn Face,’ they mask their loneliness and problems.” The UA started a steering committee to “chip away at the ‘Penn Face’ by showing the many different ‘Penn Faces’ and normalizing the sharing of struggle,” quite an ambitious goal for a steering committee.

I’m sure there are students here who both feel pressure from Penn Face and know what they mean when they use it, and I do not want to belittle their struggle. However, all three of the aforementioned institutions define Penn Face differently, and each one focuses on limited solutions. It’s actively harmful that the lynchpin of mental health activism is, essentially, a namecheck for this oversimplified and underdeveloped idea of “stress.” It’s doubly harmful that the suggested solutions for Penn Face all rely on CAPS instead of deeper, cultural fixes, and that the one institution connected to students is parroting this lame idea.

We’ve allowed people who do not know what it’s like to be a Penn student to dominate a conversation about the culture surrounding Penn students. Penn Face is a flawed idea because it’s not a Penn idea. Some reporter from the Times came down, profiled one person, referenced a poorly developed concept, and it took off. That, in tandem with the Hamlett-Reid group, means that the biggest mental health advocates on campus are not on campus. That’s where things become dangerous. My depression and my anxiety are negatively affected by this shoddy activism. Our collective mental health can’t improve when our voices are being drowned out by reporters and parents. I’m not sure what cultural changes need to be addressed to fix this, but I am sure that the New York Times and its shoe-leather reporting doesn’t have the answer.

* * *

My last therapy session as an adult was soothing. I only saw my therapist three times over the summer. We could both see improvement and she recommended I become a once–a–month patient. We had gone over mindfulness meditation exercises to prevent me from sinking too far into depression. I started walking around campus wearing what a friend calls “industrial-sized headphones,” and that’s helped with the anxiety. I left Philadelphia at the beginning of August without any sessions scheduled. I’ve kept going to that deli, but I haven’t seen my old therapist since.