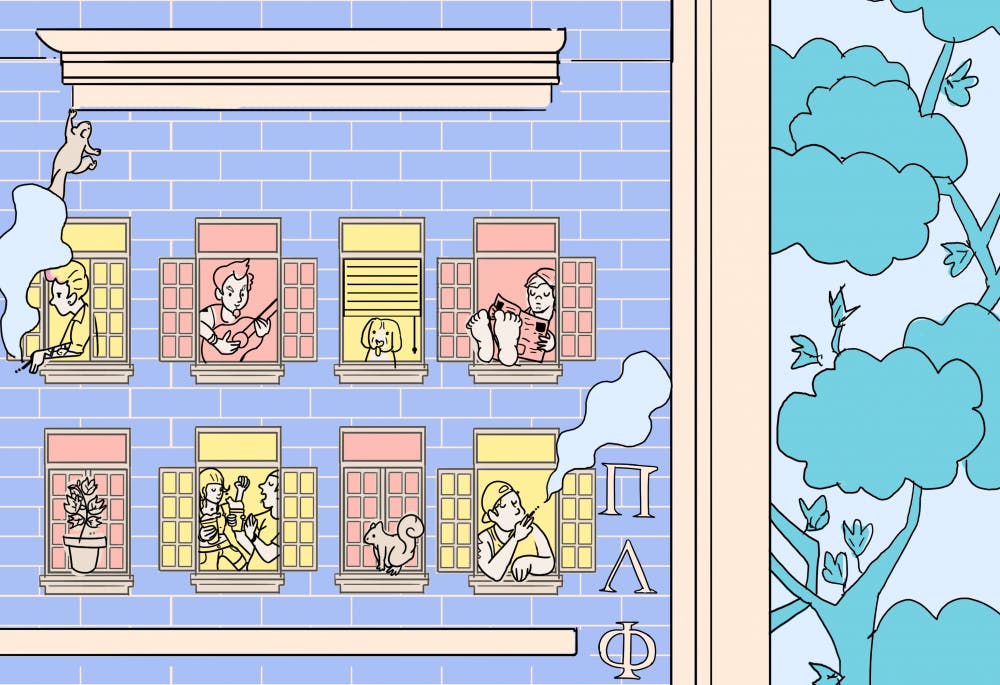

Beneath a dropped ceiling crumbling tile by tile, on a floor sticky with week–old alcohol, between walls tattooed with anthems and illustrations of classes past, 3914 Spruce Street tells a story decades deep. Since the early 1970s, the four–story dwelling nestled between Pi Kappa Alpha and Sigma Alpha Epsilon has served as home to Penn’s chapter of Pi Lambda Phi, better known as Pilam. But under the weight of debt, this has all come to an end.

Pilam has braved two mergers, a fire, and an advisory to relocate, culminating in close to a million dollars' worth of renovations that saddled them with lasting debt. In March 2018, after years of struggling to offset that debt through rent payments, the group was forced to leave.

Somewhere along the way, the fraternity has become an archetype, occasionally featured on the Penn meme page, OUPSCC. Pilam abbreviated is grungy and idiosyncratic, an alternative space facing what some consider its inevitable end.

In Kuo–Hsien Tong’s (C '89) experience, Pilam’s M.O. was band parties. The throw-downs, always rowdy, showcased music from public FM radio bigwigs to local up–and–comers, from punk to surf rock and everything in between.

The late ‘80s reveled in live performance. The CD had debuted only a few years prior; if you wanted music, you’d usually opt for a cassette. But if you were a fraternity at the University of Pennsylvania antsing for the wildest party possible, the best move was to hire a live band.

“There was one party,” Tong recounts, where “so many people were dancing on the main floor that waves of oscillation were causing the floorboards to gyrate a good foot up and down.”

As striking as the memory of an undulating dancefloor may be, the reality of the building’s infrastructure raised questions of safety. According to a University–mandated architectural review from almost two decades later, the house was burdened by “weak masonry around the walls [...] significant termite damage in structural joists and water–damaged ceilings and walls.” The frat would be stamped unsafe for occupancy and hit with an advisory for residents to relocate.

“The building had structural challenges. [It] was frequently under need of repair,” Tong acknowledges. “But I assume that’s common with a lot of fraternity houses.”

Infrastructure wasn’t the only safety issue that Pilam brothers faced—in 2003, a small fire occurred at the house, caused by a cigarette left burning on a chair.

William Kramer (W ’85, C ’85), a Pilam alumnus, describes the space as a “pit.” Holes peppered the walls, the front staircase jutted out from the building, and the brickwork was shoddy at best. “It was not quite unsafe at the time, but it was not in the greatest shape.”

Still, the place had its charms. “We had beer on tap 24/7,” Kramer says. “You can’t do that today.”

In its double life as a music venue, Pilam has hosted headliners like Wesley Willis, of Montreal, and recently, Japanese Breakfast. 3914 Spruce is home to rock history—namely, reunion shows for The Dead Milkmen, a Philly–based punk–pop group best known for MTV hit “Punk Rock Girl,” and King Missile, of “Detachable Penis” notoriety.

The annual Human BBQ reigns as its biggest bash of the year—half a day’s worth of band rotations and barbecue meat (vegan options available). Musical acts alternate between the basement and the living room. Groupies and general guests alike mill about and indulge in all shades of debauchery.

“[Pilam’s] reputation in Philadelphia was that it was a Penn–affiliated organization, so it wasn’t necessarily ‘that cool.’ But we could bring a lot of good acts, and we had the protection of the school, so we couldn’t really get shut down in the way that other underground house venues were getting shut down,” explains James La Marre (C ’11), who served as president of Pilam during his time at Penn. “We had more longevity as a stage, and could create more of a cultural impact.”

Concert poster / From Pi Lam's Facebook Page

Holden Jaffe performed at the 2018 Human BBQ as part of the folk rock outfit Del Water Gap, named for the nearby recreation area where the Delaware River carves through the Appalachian mountains. “We’re from New York, and there isn’t really a house show scene developed there,” Jaffe says. “This sort of vibrant Philly house scene is so new to me, and Pilam was the first DIY show we did there.”

It was his second time playing at Pilam; the first was in January of 2017—a Friday night in biting cold winter. “We rolled up there, and there was a bunch of bands playing. Within twenty minutes, the whole PA broke. There was probably 150 people there—talking, smoking. The energy in the room was like nothing I had ever felt in front of a totally foreign crowd before.”

Many Pilam brothers admit that they never expected to join a fraternity. For Cory Schwartz (C ’03), a musician and artist, not only was Pilam vastly different from the average fraternity on Locust Walk, but also “a real hotbed for alternative, intellectual activity.”

Pilam created room for Penn students who wavered on the social fringe, but it also accommodated Philadelphians at large. Schwartz remembers the train–hopping “anarchists” who would crash in the basement of Pilam, “spreading their ideas. And these kids were all really well read too—quoting Chomsky and stuff like that. They ended up ruining our toilet in the basement. We filled it with cement but they kept using it, so we kicked them out."

Despite the “fraternity” label, Pilam is often seen as a welcoming space for women and LGBTQ+ students. The group shifted towards an informal, gender-inclusive structure that allowed for non-male unofficial members. Sophie Germ (C ’19), one such member, de–activated from a Panhellenic sorority after feeling “like a piece of meat, in terms of being paraded around to different frats ... When I walked into Pilam, that was completely not the case.”

Photo Courtesy of Ricky Mangerie

Current brother John Willis (C ’21) considers Pilam a “perfect space to host other queer people”—Willis has helped organize a Queer Student Alliance Valentine's Day party and a gay Spring Fling party, both held at Pilam.

“People would come up to me and say, ‘This is amazing; we don’t have a space on campus. We needed this.’ We still need that, and that’s why it’s unfortunate that we lost the house.”

But some brothers have far less flattering perceptions. Pierre*, an inactive Pilam brother of color who asked to remain anonymous, found that “the aestheticization of punk by wealthy white kids was very off–putting. Their voices tend to be very loud in this space.” He finds the frat’s supposed inclusiveness selective and untrue; he believes it’s also a reason for Pilam’s current financial distress.

“Pilam at face will welcome anyone who shows interest to it, but a lot of that is because the space is kind of desperate. We struggled a lot with filling up the rooms," Pierre says.

The house is designed to accommodate up to 18 people, with rent ranging from $800 to $1100 a month. According to Anton Relin (C'19), a former Pilam treasurer, the property's manager, Apartments at Penn, allowed the group to pay their debt incrementally with the help of rent payments.

Anton confirmed Pierre's observations, explaining that the group's struggle to fill the house, even with additional female boarders, has led to the group's financial tumult.

"Pilam shows you its dumb principle to accept everyone, to being wholly inclusive, which is the antithesis to a fraternal structure. Which is: we will select the people we like, but we will really like them," Pierre says. "Pilam was an experiment of the opposite, which is: we will select anyone who takes us. Pilam was an experiment of a non–exclusive social club, and it was ultimately a failure.”

Former boarder Olivia Pawling recently published and circulated a document titled:

Pilam (as it stands) is Inherently Hypocritical due to the Misogynistic

and Bigoted Nature of all Nationally Recognized Fraternities, and

Masquerades as a Safe Space when in Reality it’s a Haven for

Narcissistic Outcasts who think Painting the Walls of their

Mansion is a Political Movement: A Concept

The document calls out the chapter for reportedly brushing assault and harassment complaints under the rug; for attracting bigots, “false punks,” and abusers; for touting a phony DIY label (“DIY is not just some meaningless word people throw around for clout points… at least not outside of this convoluted, intensely misogynistic, and disturbingly unaware circle–jerk of (a lot of) pretentious children.”)

Pawling declined to comment.

Soon, 3914 Spruce Street will be property of Drexel’s Pilam.

Like most other chapters of Pi Lambda Phi, Drexel’s chapter falls under what former Pilam treasurer Owain West (C ’19) describes as “whatever one’s normal conception of a frat is.”

“The cultures do not overlap much, or at all,” West says, adding that even the house’s iconic illustrated walls have been painted over by Drexel Pilam.

A lot of alumni find the news, to varying degrees, disappointing. Even Pierre acknowledges the loss: “I always had this feeling that Pilam, even if the people there were wealthy white people who didn’t get it, even if they were posers, even if the place was disgusting or literally falling apart, I guess there was this comfort that other people also felt, that Pilam was there for you. Now that’s gone.”

Omar Martinez (C ’21), a Pilam brother, thinks the change will be a good “opportunity for Pilam to rebrand itself, as an organization versus as ‘that house.’”

While Monica Yant–Kinney, a spokesperson for Penn's Office of Fraternity and Social Life, said in an email to The Daily Pennsylvanian that the chapter was "not evicted" from 3914, many members described their removal as an eviction.

At the end of the day, Pilam is its people, culture, and musical history—however inclusive or grimey or niche they may be. Pilam extends beyond a plot of land. Pilam is the message slathered behind the lime green of their basement bar, the single white–painted statement: “NEVER STOP HANGING OUT.”

La Marre, the former Pilam president, says he’s nostalgic for the people, not the space, though he acknowledges he hasn’t been back at the house for a while.

“This might sound a little privileged to say,” he adds, “but I think it’s kind of punk that they got kicked out.”