In Professor Kirk’s English class, there's talk of bitcoin, the history of fashion, and the latest Wing Bowl, which is an annual buffalo wing eating contest. Not exactly the usual topics of discussion in class. This is ENGL145, Advanced Nonfiction Writing: XFic, where students take the raw material of experience and transform it into a compelling narrative that will be bound in XFic, Penn’s premier literary journal in experimental nonfiction.

Experimental nonfiction, also known as creative nonfiction, is a genre that presents real people and events in a compelling, vivid manner. It’s like jazz—a rich mix of flavors, ideas, and techniques, some of which are newly invented and others as old as writing itself. An essay, a journal, a personal diary, a poem, or a combination of everything.

“I thought it was one thing, something like a history book, but this course showed me that nonfiction can be a hundred percent of what you want it to be. It showed me ways of taking what we have in the world and make it really creative, engaging, and beautiful,” Nicole de Almeida (C ’19) said. “If you invent a world, you have free reign to do whatever you want, but if you talk about something real, there’s only so much you can do. But if you manage to reconstruct it in a very compelling way, you extend people’s horizons by attracting them to learn new things about the planet they live in.”

Every narrative starts with writers directly engaging with the reality of their experiences. For example, Marina Gialanella (C ‘20) is particularly interested in fashion and the history of fashion design. She marries this interest with the contents of the class, designing clothes and documenting her thought process—all while receiving credit.

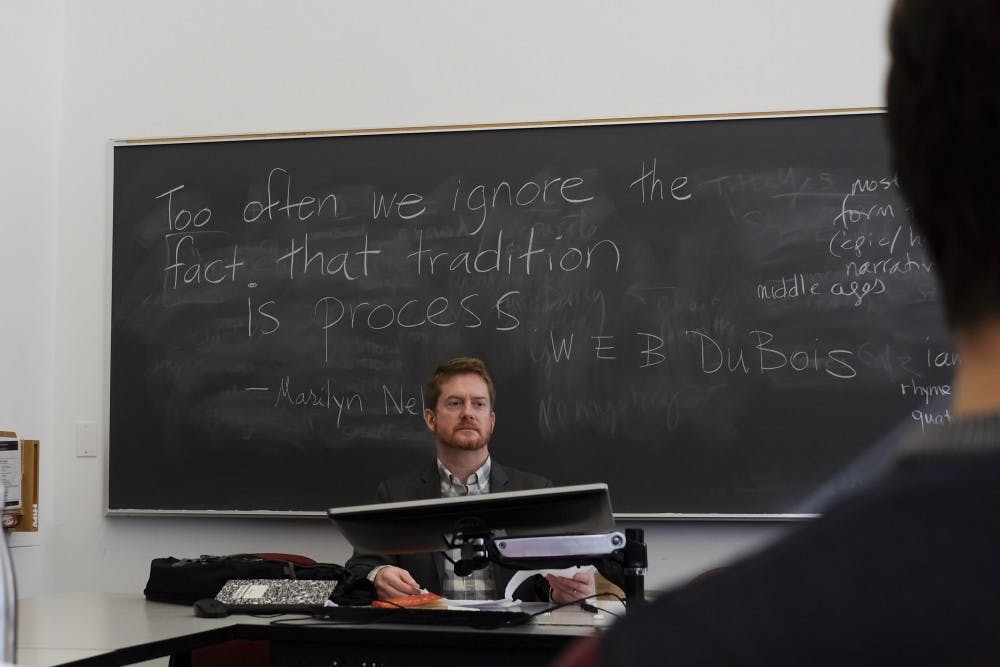

Each week, the class is formatted as a workshop, with students pairing off in editor/writer relationships. Stories are subject to “a battery of rigorous and boundary–defying tests,” Kirk described. “The hope is that by enacting a few thought experiments, and being as conscious as possible about the process of arranging and composing our collected material—how do we perceive, how do we interpret, how do we arrive at meaning—and by engaging the literary superpower of daring to take the Radical Choice at every possible turn, we will make more authentic and mind–blowing discoveries.”

The sheer diversity of students the class attracts also lends value to the writing process. The pairing off of students allows each writer to reevaluate their understanding and see their original topics through new lenses. From a student working at the Penn hospital to another from the Curtis Institute of Music to the Wharton professor sitting in at times, there’s a plethora of knowledge to draw from to shape the student’s own experience.

By the end of the semester, students need to submit a full draft, but Kirk encourages them to still see it as a work in progress. “Something Jay always told us is that it’s always a draft. So never did he expect a complete piece, nor did he want us to regard our pieces as finished works. And that gave me a lot of room to breathe, because I didn’t have to worry about it being done,” Nicole said.

The concept of perceiving a work as a work in progress extends its life beyond the class; it’s no longer something “for the class” but something more personal. In the environment of always having the pressure to finish things on time, we are so focused on finishing a task and proceeding to the next, but having the liberty to view an assignment as something that doesn’t need to be finished is creative and cool in itself. And this is what Kirk’s class brings to the students.