As our TikTok pages, Instagram feeds, and Pinterest boards become inundated with blazing pinks, purples, and the ever–so–persistent threat of low–rise jeans, one thing has become clear:

Y2K is back.

Today, it’s not the looming threat to our online calendars and data storage so much as it is the fashion trend that dominated the early 2000s. Y2K fashion is unabashedly kitsch and unapologetically exuberant. The subculture features an assortment of staples, including camis with lace detailing, saddle bags, as well as barrettes and butterfly hair clips in multi–colored shades. Y2K is the aesthetic seeping into our social media feeds and the hashtag of every Depop description. However, amid all the fervor over pleated skirts and cropped cardigans, one question prevails: Where did Y2K fashion come from?

Most people would cite the Bratz dolls or even films like Clueless and Mean Girls. What these responses fail to recognize is the significant contributions of Black culture in defining the Y2K aesthetic. Flipping through the lookbook of 2000s fashion makes it clear that certain pages have been ripped out.

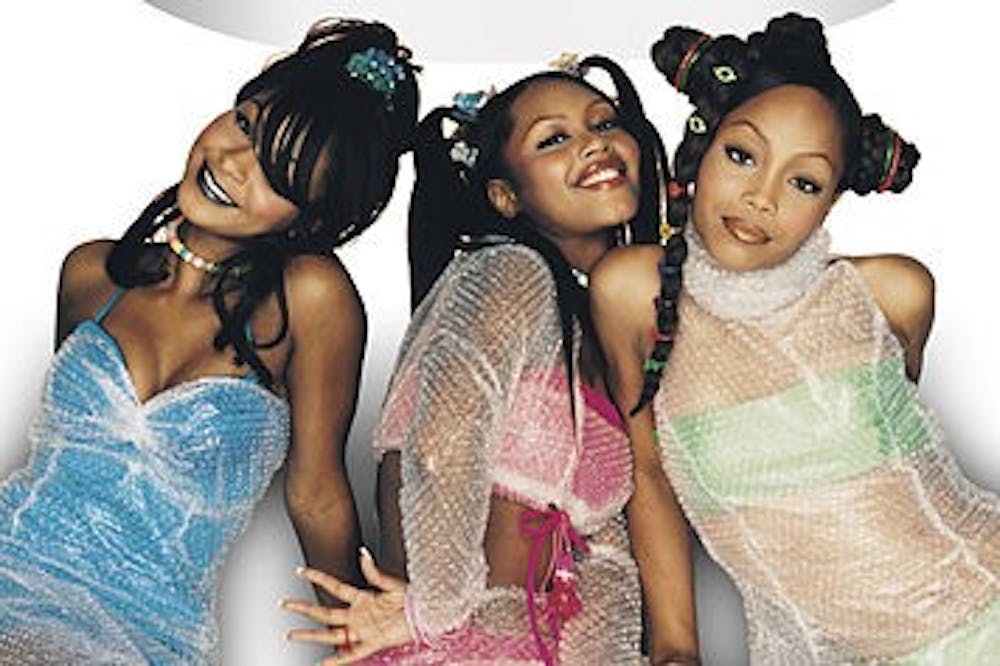

Some consider the truest form of Y2K fashion to be the technology–inspired wave of tight leather pants, metallic clothing, and silvery eyeshadow. This particular style featured utilitarian chic clothing, shiny materials, and techy accessories. The futuristic, sci–fi reminiscent iteration of Y2K style peaked in late 1999–early 2000, at the pinnacle of the dot–com boom. However, fashion history often overlooks or underrepresents the influences of Janet Jackson, Missy Elliott, and Blaque—musical artists who, in part, defined and revolutionized the aesthetic. These artists aligned with Afrofuturism, a concept dating back to the '70s, that projected Black space voyagers into a fantastical, avant–garde landscape. Notably, the conceptualization of Jackson’s music video for “Scream” featured shiny metallics, shoulder pads, and other elements of the space–like reverie that captured Afrofuturism and Y2K fashion.

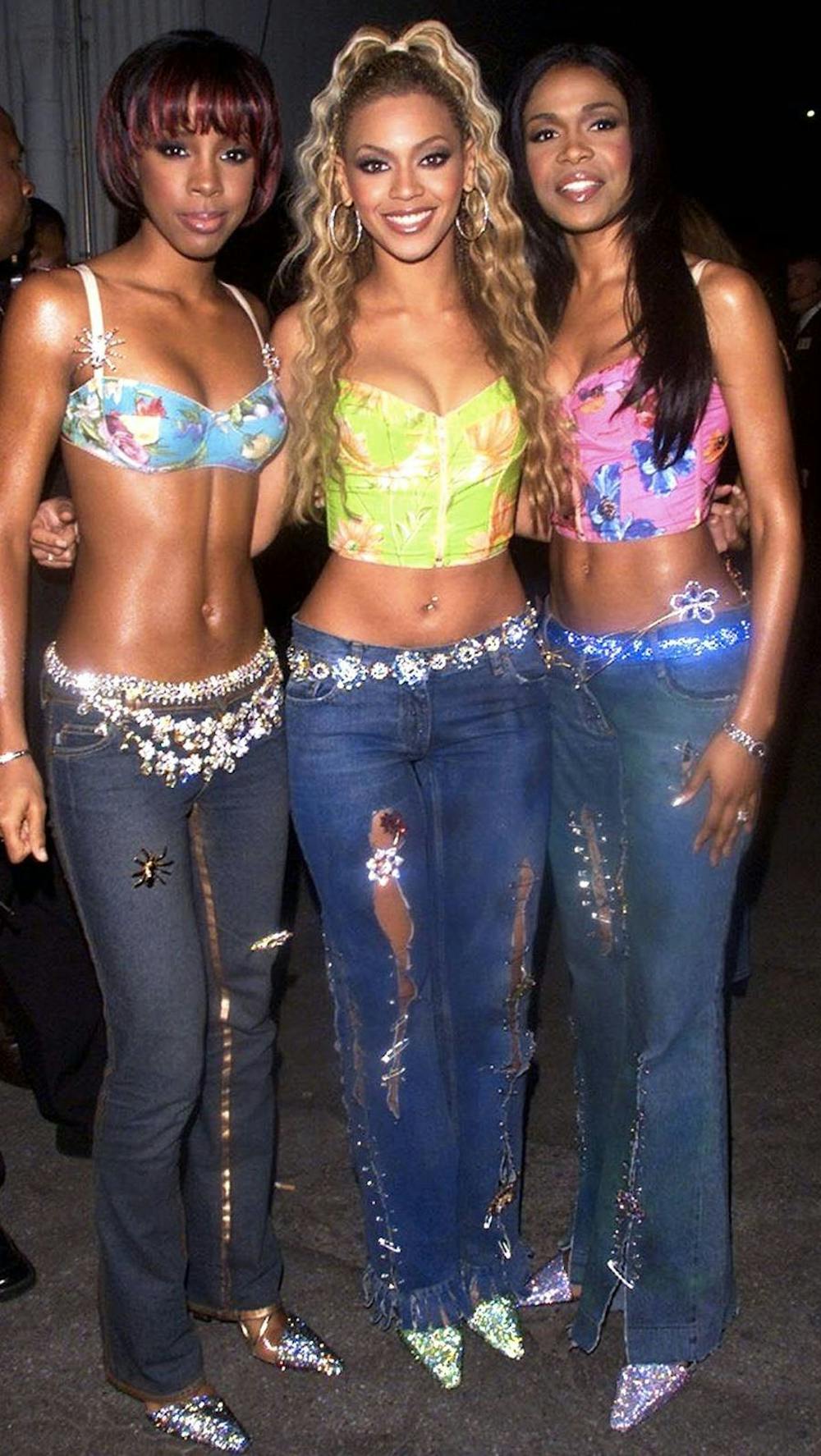

It turns out that much of the iconic Y2K aesthetic dominating our digital landscape, as well as other iconic 2000s fashion staples, are similarly the products of Black culture. Girl groups like Blaque, 3LW, and Destiny’s Child both popularized and cemented key aspects of the Y2K style— sporting low–waisted jeans, neon camisoles, and mesh shirts. The logomania and fixation on designer symbols that pervaded Y2K fashion were also inextricably linked to the legacy of Dapper Dan, a Harlem couturier who screen–printed luxury brand logos onto his own designs.

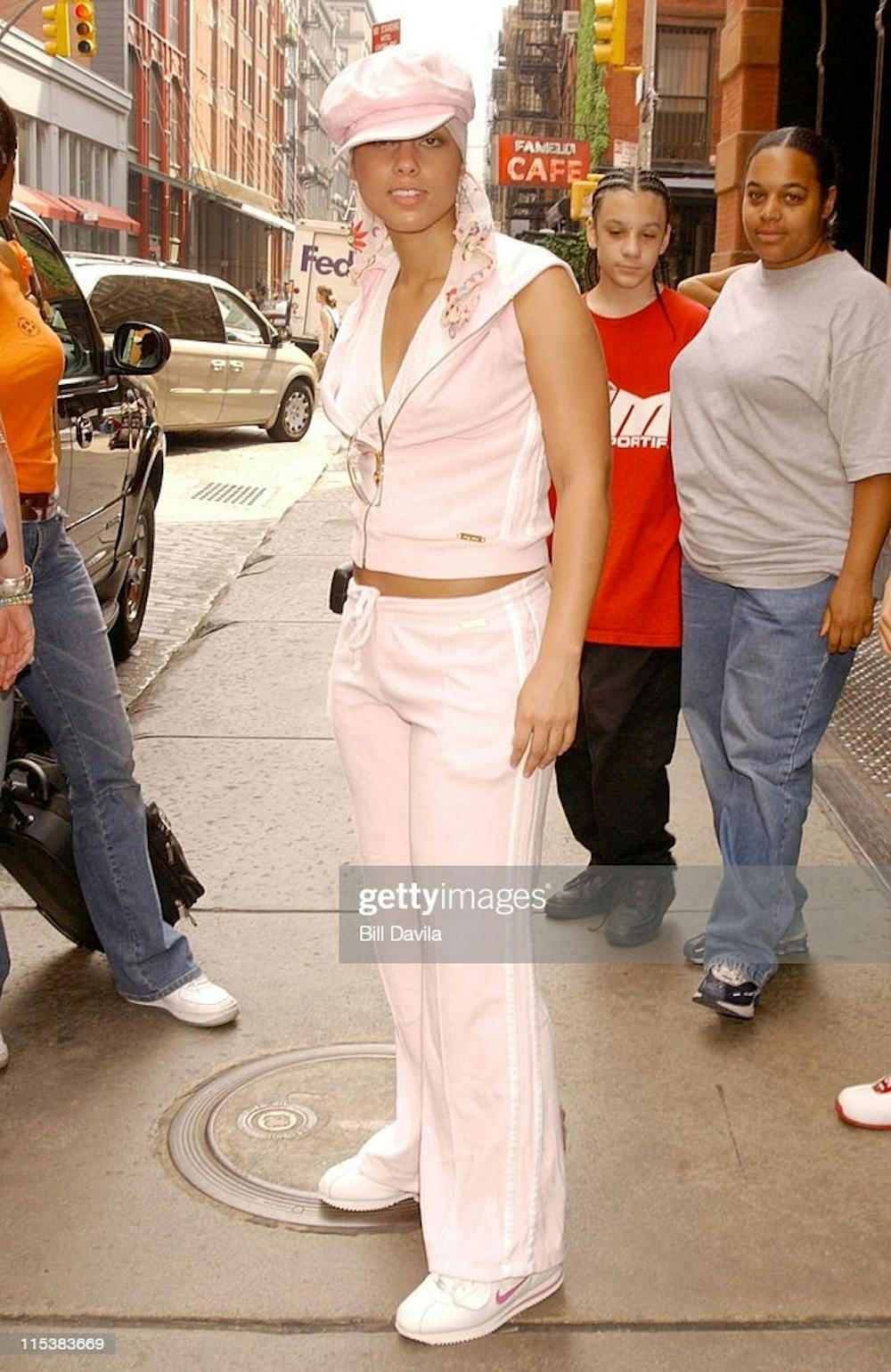

Velour tracksuits, another staple that dominated the 2000s, are synonymous with the Juicy Couture brand. But before Britney Spears and Paris Hilton arrived on the scene, hip–hop artists like Salt–N–Pepa and Missy Elliott wore athletic clothing as fashion statements. A Complex article discussing the history of the tracksuit alludes to the Juicy Couture craze but fails to mention Baby Phat, a clothing brand founded by Kimora Lee Simmons that indisputably contributed to the velour tracksuit mania. Simmons’ tracksuits were also popularized by Black artists, sported by the likes of Alicia Keys and Meagan Good.

Even oversized gold hoop earrings have their roots in Black culture. Hoop earrings originated in Africa and quickly became a core component of Egyptian royalty. In the '60s and '70s, they became associated with African beauty when Nina Simone and Angela Davis began wearing them. In an article for The New York Times, jewelry designer Jameel Mohammed discussed the erasure of Black history from popular fashion items, saying, “Black style has to be contextualized differently in order to be seen as luxurious."

Feb. 28 marked the end of Black History Month, but the acknowledgment of Black contributions remains just as paramount as ever. It’s vital that we work toward not only representation but recognition of Black influences on style. We need to not only be cognizant of the enduring legacy of Black culture on hallmark fashion movements, but actively appreciate it. For style writers and historians, this means re–examining the ways in which fashion history is conceptualized, taking note of who is mentioned, and making an active effort to acknowledge Black erasure.

Ultimately, we don’t just need to re–examine history. We need to rewrite it.