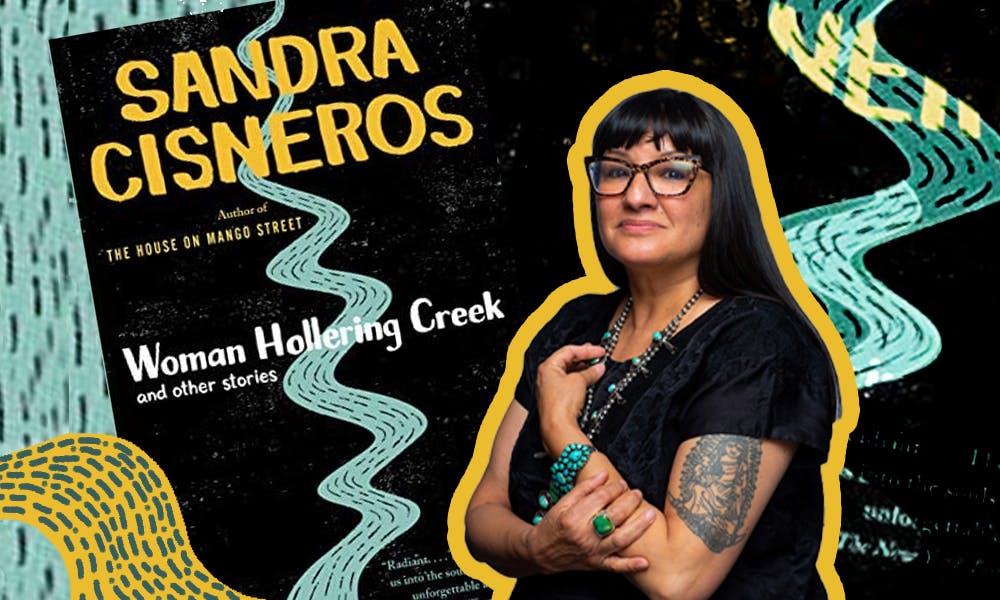

Every word of Woman Hollering Creek, Sandra Cisneros’s award–winning collection of short stories published in 1991, was written with the truth in mind. Sure, Cisneros jumps between narrators and outlandish scenarios with practiced ease, but there are real–life memories behind all the heartache and longing of her stories. In all her fiction, Cisneros drives toward “the real truth, especially the truth I’m not aware of.” Woman Hollering Creek is no exception, being born of a balancing act between the conscious and the unconscious—between reality and memory.

However, thrust into literary fame with the publication of her runaway hit The House on Mango Street, the Mexican–American writer found herself in a bind: How far could she walk down memory lane? As if to answer that question, Cisneros chose to delve even deeper into the recollection–heavy style that characterizes her early work. For Woman Hollering Creek, she went inward, melding deep childhood memories with cultural iconography. As she immersed herself in her work, Cisneros began blurring the lines between her day–to–day life and her fiction; she describes waking up in the “middle of the night, convinced for the moment that she was Inés,” a character she was then developing. “Her dream conversation [as Inés] then became [...] dialogue” in the final work. This deep, introspective commitment to her craft made Cisneros a household name in the Chicano literary renaissance.

Boasting three acclaimed books, Cisneros quickly rose to the forefront of the Chicano movement in the early ‘90s. Awards, book tours, and big–sum advances followed the publication of The House on Mango Street—but with the fame came personal upheaval. Cisneros describes a dramatic shift in her relationship with her father as a result of her success: The author went from living on a shoestring budget to sending her once–disapproving father pictures of her vast earnings. "Oh, my God,” he would tell her, “how many years would I have had to work to make that sum?" Given this permanent disruption to Cisneros’s family, it’s no surprise that domestic life—with all its pains and pitfalls—makes up the foundation of her fiction.

In Woman Hollering Creek, men and women get married, children grow up, and marriages disintegrate. Cisneros brings a deft eye to everyday issues of upheaval, loss, and renewal. Throughout, poverty and violence are hidden as ever–present facts of life. In Cisneros’ world, children huddle in shacks and churches crumble from neglect. Violence finally breaks through the surface—such as when a man is accused of murder in One Holy Night, or when a woman is killed in Eyes of Zapata and her remains are gathered “in a small black bundle." These storylines, albeit their more sensational details, are spare and achingly familiar.

Yet even in all this desolation, Cisneros finds tenderness. In the titular story, an open wound releases “an orchid of blood,” recasting an act of violence as the triumph of life over adversity. This style is characteristic of the entire collection, which features moments of weariness punctuated by bursts of inventive language. Cisneros describes a dying grandfather as going to his “stone bed,” and likens a character’s voice to “hollow sticks, or [...] the swish of old feathers crumbling into dust.” Guided by an ear for the strange and the sonorous, Cisneros ably bowls the reader over with just a few words. The effect is particularly moving when her judgments are couched in the playful voice of a child. Take the story Mericans, in which the narrator—a little girl—asks: “Why does holy water smell of tears?”

Beyond these stylistic flourishes, Cisneros adheres to broader linguistic and formal experimentation. The bilingual writer peppers Spanish words into her stories, relying on the reader to keep pace. Rattling off swear words and sweet nothings in the same breath, Cisneros brings the reader directly into her world of "abuelitos," "arroyos," and "chachalacas." She wields the same creativity for questions of genre, often straddling the line between poetry and prose: The stories here are delivered in vignettes, some as short as five paragraphs. But as Cisneros's career attests, all this innovation has paid off rather than alienate her readership.

By relentlessly pushing the envelope, Cisneros has paved the way for today’s Chicana writers. As one of the very first Chicana writers to reach media prominence in the nineties, Cisneros rose to fame in an environment that had seldom paid attention to voices like hers. Yet she has continued to barrel forward in the decades since her debut, doubling down on the themes of immigrant identity and cultural alienation on which she first made her name. Years later, her work remains a source of inspiration for aspiring Chicano writers and a classroom staple across the nation. Books like The House on Mango Street are now regularly assigned in classrooms, so Cisneros’ words continue to resound throughout generations. It hasn’t been an easy road by any means, but, prone to taking her characters to hell and back, Cisneros knows that hard–won victories are all the sweeter.