What makes Chinese different from any other language? On the surface, the most prominent difference is how it looks: Chinese employs what appear to be elaborate, blocky symbols that give no place of entry for the untrained eye. The English and Chinese languages both use sequences of characters to make sounds and meaning, but what sets Chinese characters apart is not only their seeming complexity, but also their ability to convey an elaborate history and culture behind the strokes.

One common misunderstanding about Chinese characters is that they are picture writing. But this isn’t completely true or false. For example, the character for human, “人 (rén),” originally evolved from a pictograph that was made in likeness of a human. However, as concepts get more abstract—things like “word” or emotions like “love”—the meaning of the character cannot be realistically depicted. The visual components are then often combined to form a larger meaning, or are chosen for the sound they correspond to. However, even when Chinese characters are put together to form more complex words, they still keep their individual connotation.

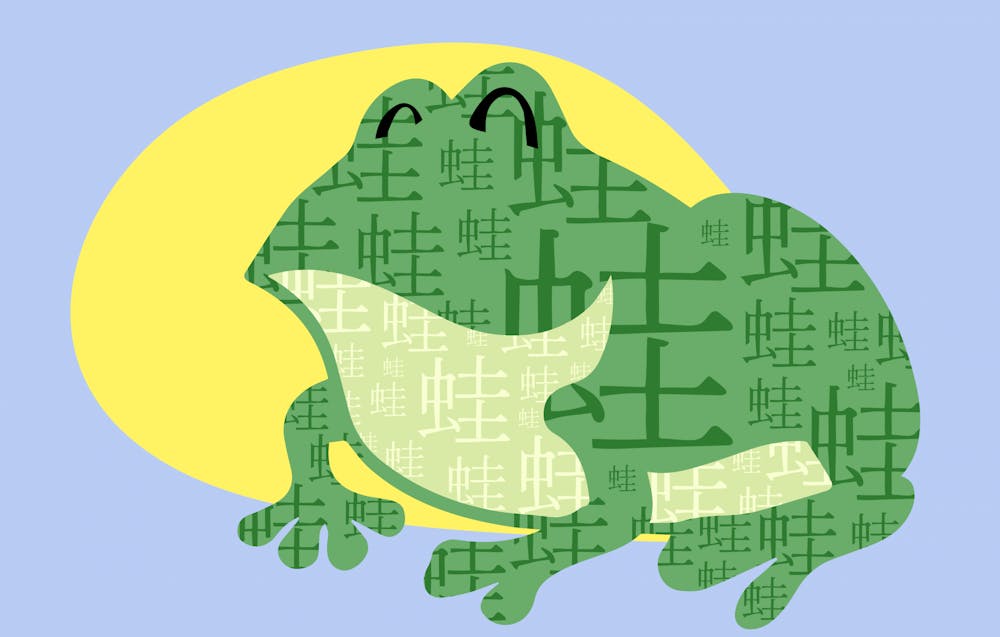

The individual symbols in phonetic alphabets represent sounds but are inherently meaningless. In contrast, Chinese characters, the smallest units of language, have their own individual meanings. “成语 (chéngyǔ)” is one example of this characteristic in practice. These are usually four–syllable words or idioms that convey a value, admonishment, or wisdom, sometimes using characters that may seem unrelated on the surface. An instance like “井底之蛙 (jǐngdǐzhīwā)” is but one of many examples illustrating this complex relationship between the literal and the figurative: Literally, it means a “frog at the bottom of a well,” but it represents “a close–minded or naïve individual.” In fact, there is an entire tale that accompanies this chengyu about a frog who makes assumptions about the world beyond its little well based on what it observes from within.

The origins of these idioms find themselves in the history and the culture of China, but also in the cultures of neighboring countries that adopted Chinese characters. Each adage bears a weight that may span centuries, with a deeply rooted cultural significance and identity. Many chengyu, for example, originated in poetry or prose. Over time, these have been extracted from that original context into the common lexicon. Their meaning has carried forth but also evolved with the changing times.

Calligraphy is often associated with chengyu, and allows for a combination of a meaningful message with an artistic interpretation. Many scripts of calligraphy were practiced throughout history, and many continue to this day. The decorative nature of the art form and the accompanying significance of the text makes for a gift that can be given to a friend, sending them good wishes, or be used as a formality in official events. Regrettably, as with many traditions in various cultures, young people are slowly forgetting the value behind these art forms that were previously passed down from one generation to the next. This is a shame, since in a quickly changing world, the far–reaching history of calligraphy may bring us some comfort and a sense of connection.

Chinese characters can be appreciated aesthetically too, especially if they’ve been hand–written. They also have the ability to craft a series of sentiments, thoughts, and nuances in what is essentially a few concise syllables. Indeed, Chinese art sometimes employs a character or two in the composition. The weight of the character adds to the message and interpretation of the piece as a whole, creating a balance between the literary and the visual.

Chinese characters come from a culture with a long history and have evolved and changed alongside that culture. In a way, they embody their role as a communicative tool perfectly, as a beautiful balance of form and function. They gracefully and dutifully carry the weight of a complex form, a heavy cultural baggage, a profound artistic potential, and age–old wisdom in each stroke of the brush.