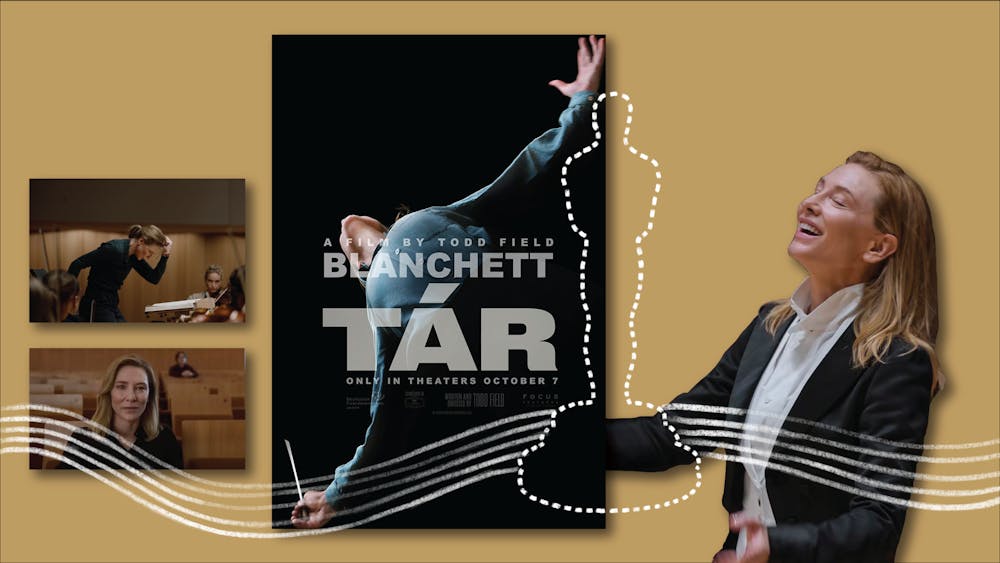

Who is Lydia Tár?

That is the question you will ask yourself while walking into and out of Todd Field’s thrilling and terrifying new drama.

Lydia, played by the incomparable Cate Blanchett, is introduced to us backstage before a live interview. She sucks in heavy breaths, rearranges her face, hair, hands, and smooths her jacket as if preparing for war. Her nervous flinches give way to shots of expensive suits prepared for her, expensive pencils she wields, and expensive music in her hands. When New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik (playing himself) finally introduces her, Lydia walks into the spotlight, unnaturally collected, as a perfect blank slate. As she turns her mild smile on the crowd, you realize you have just witnessed this woman constructing herself.

Tár follows the fictional acclaimed composer and conductor Lydia Tár. Her list of accomplishments is too long for a single review: she’s one of the only female conductors to lead a major orchestra (the Berlin Philharmonic), she called the Leonard Bernstein her mentor, she’s recorded basically every piece of classical canon, and she created a scholarship fund to give young female musicians high profile internships. Did I mention she’s an EGOT? When we meet her, she’s at the peak of a deeply illustrious career, releasing a memoir and about to record Gustave Mahler’s fifth symphony. By the end of the film you will feel as though Lydia Tár is realer than most public figures, yet you will still not understand her at all.

Lydia Tár has clearly smashed the glass ceiling of classical music in this alternative universe, but this film isn’t here to show her rise. It’s here to watch her fall.

Lydia, we learn, is both a genius and a monster. She is a brilliant musician, a talented conductor and composer, and charming when she wants to be. She is also a bully and egotist, with a predilection for the young female musicians she mentors.

Tár begins on a Manhattan stage and then follows Lydia back to her home in Berlin. As we move through expensive private planes, Lydia’s intimidating and luxurious concrete penthouse, and the féted halls of the Berlin Philharmonic, Lydia exudes pure confidence, authority, and menace. It is clear she rules this glittering world with an iron fist.

As it continues, Tár milks these moments of danger so much that it almost transforms from a drama into a thriller. Field peppers in moments of unease, subtle mysteries that grow in suspense. Lydia is married to Sharon, the Philharmonic’s first violinist, and together they have a young daughter Petra; but domestic troubles abound. Sharon, played by the fantastic Nina Hoss, is never seen without dark circles, and she hovers around Lydia with wary intimacy and more than a little resentment. Concurrently, Petra is being bullied in school. An assistant director at the orchestra needs firing. When no one is looking, Lydia’s loyal assistant (Noémie Merlant) stares at her boss with both tenderness and shocking rage. Lydia is receiving strange gifts from former students and hearing odd noises. Rumors are swirling about the nature of her mentorships. And throughout all this, Lydia is drifting towards the orchestra’s newest and prettiest cellist.

The film could be labeled a ‘cancel culture’ tale, which while that does describe its plot, this labeling is a disservice to the ideas Tár presents. Tár is a true meditation on Lydia’s world, the rarified world of classical music. It is truly interested in power, in guilt, and in the ways in which the public and media elevate brilliant people higher than their actions. Lydia Tár is certainly swept up in the phenomenon of cancel culture, but Tár is less interested in what that abstract term means and more about the ways in which Lydia has been able to abuse her power for so long. Todd Field’s script refuses to either admire or despise Lydia; it leaves this judgment up to its audience. In fact, by rejecting any moral absolutism, Field seems to suggest that Lydia the monster and Lydia the genius are inextricably connected.

This spiraling character study truly belongs to Cate Blanchett, who is nothing short of extraordinary. As she conducts, she appears to summon sound into existence with a sweep of her arms. She commands every room and every scene with her sheer overwhelming presence; at home and at work, she moves like an honored guest waiting for her spotlight.

Lydia runs big and small, as the tiniest flicker in her eyes or a piercing shriek may signal the same incoming breakdown. Blanchett’s performance is wrapped up in all of Lydia’s shifting identities: maestro, loving mother, and faithful wife. Tár is best as a dark character study; the occasional glimpses into what makes Lydia powerful drive the film forwards. The control she wields controls her.

Even during scenes devoid of any real conflict, danger, or monstrosity, what makes Lydia tick is always under the surface. “Honey,” she almost tenderly tells her daughter, who has arranged a stuffed animal orchestra and wants to give them all the baton. “It’s not a democracy.”