After R&B singer Jhené Aiko lost her older brother Miyagi in 2012, she spent the next five years losing herself. Whether it was abusing controlled substances, immersing herself in meaningless relationships, or jetting across the world to escape her feelings, there wasn’t much she wouldn’t do to find solace from her pain.

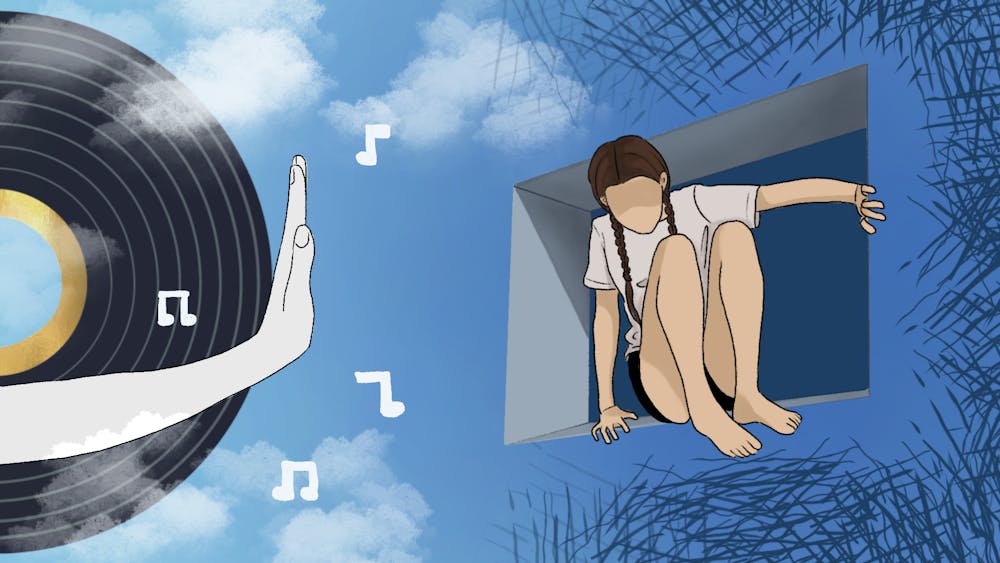

Her album Trip details her full experience processing this loss—including everything she did to avoid the pain, even if she’s no longer proud of it. As a result, on the first listen, it may seem to glorify the fleeting highs found in drugs and love, as many other artists in the music industry do. Yet, throughout the album, Aiko references the void that remains without her brother. Rather than completely avoid the sensitive topic of escapism, Trip seemingly embraces it, only to firmly renounce it in the end—setting Aiko apart from other R&B artists. The very structure of Aiko’s album reveals that any relief borne from these methods is only temporary.

Popular R&B artists such as The Weeknd and Chance the Rapper fall into the trap of portraying substance abuse as a valid way to run away from the noise of everyday life. On their songs “Can’t Feel my Face” and “Smoke Break,” they talk about employing various drugs as a means of stress relief or an artificial confidence boost. Portraying these harmful methods of “recovery” in popular music distinctly impacts their audience’s social response to their personal woes. As outlined in a study conducted by JAMA Pediatrics, humans learn by example. Coupled with America’s idolization of celebrities, as we consider their actions as markers of what’s “acceptable” or what’s “taboo,” famous artists portraying drugs in such a positive light only normalizes and promotes substance abuse. This rhetoric has adverse health effects on the entire population, beginning with the adolescents that frequently listen to such music.

Aiko takes a different stance. Though her music also heavily discusses these substances, she differs significantly in one key aspect: Her album doesn’t portray them in a positive light, being sure to ground every fleeting high with an impactful, more permanent low. Instead, she encourages introspection and self–evaluation from her listeners, all to further their journeys of true personal healing.

Aiko uses a few methods to combat the glorification of escapism. The very structure of her album is set up to illustrate her path through the pain. The album begins on a somber note, with a brief interlude giving way to the melancholic melodies of "Jukai." Then, as she begins to lean into avoidant tendencies, there’s a brief period where Aiko is caught up with a toxic love interest, who temporarily allows her to forget the pain of losing her brother. However, similar to the honeymoon phase, this sense of euphoria doesn’t last for long.

Aiko quickly falls back into a depressive state that leads her to experiment with powerful drugs. There’s a stark contrast between these deceptively sweet songs and the horrors described on “Nobody,” “Overstimulated,” and “Bad Trip,” which directly follow this romantic high. The ambiance of “Bad Trip” is the most disquieting of the entire album: a combination of singing, talking, screaming, and crying as a whistle shrieks hauntingly in the background. At this point in the album, the listener feels the full intensity of her pain, empathizing with the deceitful nature of these substances. Though she is discussing these substances in great detail, it's hard to say that she’s attempting to promote their use.

Then, the back end of the album experiences a dramatic shift in lyricism and sound, as Aiko frees herself from her vices. There’s a distinct, lasting sense of optimism through the final song. “Sing to Me” is the point of her biggest revelation, in which she embraces her role as a mother with a new vigor instead of succumbing to the temptations of escapism.

Aiko has confirmed this analysis in a viewpoint in Rolling Stone, where she discussed neglecting her first daughter while she was leaning heavily into problematic tendencies. “I feel like there were times where I felt like I wasn’t giving [Namiko] as much attention, because I was just so out of it and trying to escape everything,” she says.

Listening to this album, it's possible to ignore Aiko’s underlying message. We'll inevitably all have problems that we wish we could avoid—ranging from a tough day at school to the loss of a family member. Instead of using societally popularized methods to escape the pain, we should take cues from Aiko instead. As she demonstrates throughout Trip, attempting to escape our problems is futile.

They’ll always catch up in the end, and as the famous saying goes: the best way out is always through.