An A24 film is defined by two unmatched qualities: surrealist art and realist relationships. Grounded in these A24 principles, Beef reveals the underbelly of humanity, ascribing a certain proposition to the audience: “anger is just a transitory state of consciousness.” And moreover: it’s okay to be angry.

Predecessor films like Everything Everywhere All At Once, Minari, and The Farewell cultivated an environment from which Beef could flourish. Beef captures a reality, even if fictional, where Asian Americans can be depicted as dislikable, disagreeable, and even despicable without being met with heady resentment from either Asian or American viewers. Director Lee Sung Jin’s ability to capture the mosaic of Asian American identity is partly why Beef is currently ranked first on Netflix’s Top 10 list for the United States, and third overall, with over 34 million hours watched by viewers.

Beef’s success begs the question: How does modern film and television begin to depict a variety of Asian American stories on screen without falling into predictable tropes?

First–generation Asian American have few characteristics that have been societally validated and accepted, including, but not limited to, ambition, studiousness, and contentment. We live out the residual of our parents’ desires for success stories, constantly harvesting a weird amalgam of gratitude, fatigue, resentment, love, and, most of all, rage.

Since rage is something that is neither shown at home nor outside, where is it externalized? Media seems to provide one such avenue to externalize these complex emotions. Through Beef and its Asian American actors, Asian Americans can give themselves license to recognize and resonate with the otherwise taboo emotions that form around immigration, family, and self–identity.

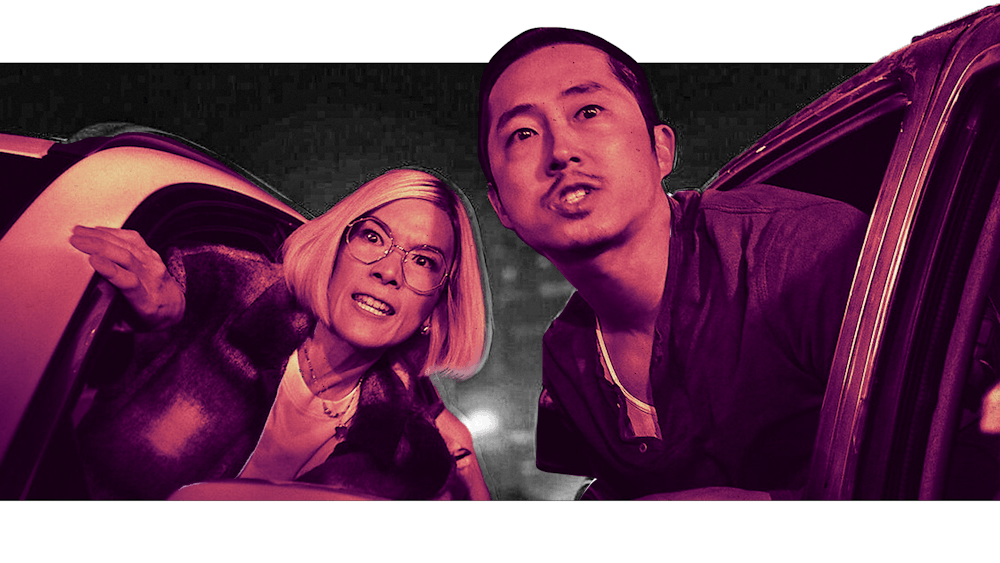

Beef approaches this bold emotion through a relatable and unassuming angle by opening with a small car incident, one which most people would have been content to internally simmer over. However, Danny Cho (played by Steven Yeun, of Minari, Walking Dead, and Nope fame) and Amy Lau (played by Ali Wong, of literally everything) refuse this. After Amy sharply cuts Danny off in a Costco parking lot, a highway chase ensues, ending as they turn into a suburb and Amy pretends to ram into Danny’s car. The plot begins here: a spiral of mutually assured self–destructiveness and pure rage.

The first episode was an implosion filled with the misdirected anger of two deeply hurt people. After the car chase, Danny painstakingly creates a plan to enact revenge, recording Amy’s license plate number, finding her house, and pretending to repair her property. The resulting act of vengeance? Pissing all over her bathroom floor. When the first revolting streams of yellow catch Amy’s eye, she doesn’t lunge for the phone to call the police or just leave a bad business review; she runs outside, marks down the license plate number, and holds a gun to Danny’s image on her phone.

These volatile reactions aren’t intensely graphic, but they certainly lack self–control, and these characters seem increasingly void of any instincts of self–preservation. It’s almost cathartic to watch the characters act without thinking: to act as simultaneous villains and heroes. And in all this, race—the inherent key to most Asian American films—simply adds another texture of complexity instead of becoming the complete foundation. Intergenerational trauma and family loyalty remain strong themes. Danny promises his Korean parents a house while taking care of his younger brother, while Amy crafts her image as wife, mother, and business owner.

These cruxes of identities can unfold along with the deep, human rage that happens in Everything, Everywhere, All At Once. Beef shows a humanity to Asian Americans that most people are uncomfortable seeing in real life, dispelling stereotypes like the model minority myth. As Korean American author and professor Cathy Park Hong writes in Minor Feelings, “Minor feelings are also the emotions we are accused of having when we decide to be difficult—in other words, when we decide to be honest.”

Beef is a show about expressing honest feelings, both major and minor—unearthing emotions once suppressed and healing the burgeoning resentment that threatens the erupt. In Beef, the Asian American experience is portrayed in a manner that is accessible to all. The characters are allowed to expose the underbelly of their inherited traumas and rage, to endure the consequences of things they didn’t deserve.