Senator Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) pushed to fast–track a TikTok ban in March, which was then blocked by Senator Rand Paul (R–Ky.) on Thursday, March 30. Supporters of the ban believe that TikTok, owned by Chinese company ByteDance, is being used by the Chinese government to spy on Americans by gaining access to their devices' data. Opponents claim that banning TikTok would be akin to violation of free speech, and that the amount of data being taken by TikTok is no more than any other app.

This scare in the U.S. is a part of a wave of criticism against Chinese–owned companies. In mid–2020, India banned TikTok, as well as other Chinese–owned apps, with the government claiming that these Chinese companies were sharing users’ data.

So, how did the TikTok scare get this far?

Sino–U.S. relations have been rocky, to say the least. In the mid–19th century, after an increase in immigration from China to the U.S., Americans felt threatened, spawning a distaste that led to “Yellow Peril.” In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. for 10 years. Drawing on feelings of racial hostility and anti–immigration sentiments, this act would not only affect Chinese immigration but also lay the foundations for future exclusion based on ethnic group. The government attempted to convince white Americans that their jobs would be protected, and that the status quo would remain “white.”

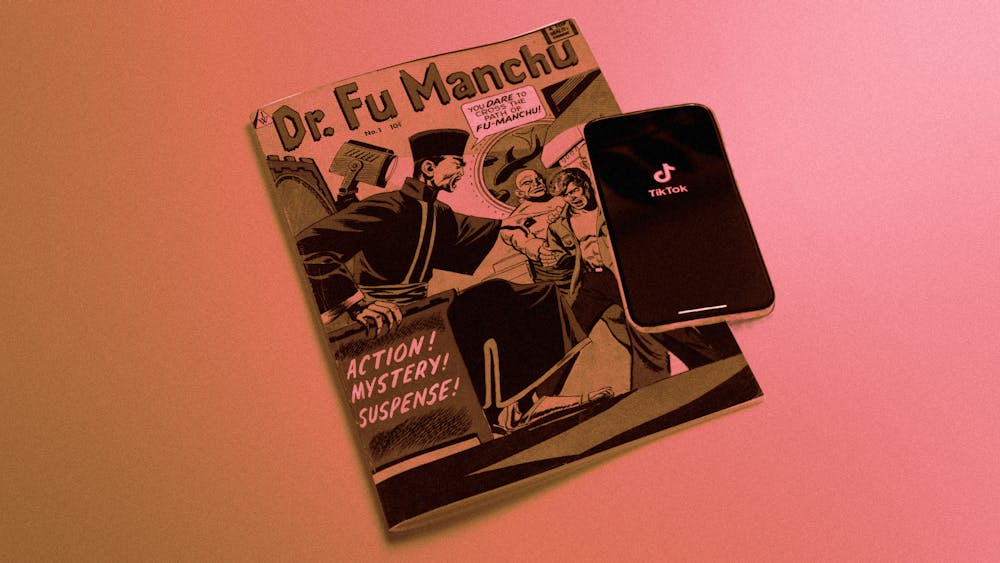

Julia Lovell explains in The Guardian that “Respectable middle–class magazines, tabloids, and comics alike spread stories of ruthless Chinese ambitions to destroy the west.” One such media example was the character Dr. Fu Manchu, the villain of stories written by Arthur "Sarsfield" Ward under the pseudonym Sax Rohmer. Fu Manchu first appeared in 1912. Fu Manchu was depicted as Chinese, wearing traditional Chinese clothing and donning a long, wispy mustache. Lovell explains that “Rohmer peddled fantasies about ruthless international Chinese conspiracies to his millions of readers.” The effects of the Chinese Exclusion Act were long–lasting, and its immediate effects can still be felt decades later.

The TikTok scare isn’t the first of its kind. In 2007, the toy company Mattel recalled about 21 million toys that were produced in China. They cited the Chinese manufacturing companies as having exported substandard toys that were potentially poisoned with lead paint. Mattel later apologized, saying that the large recall was overkill for one faulty product and that the problem arose from Mattel’s design flaws, not the Chinese manufacturers.

This large response and quick blame on China shows the lasting effects of Yellow Peril. Lovell notes that, “In almost any trouble connected with China, the old fears easily resurface.”

Now, these "old fears" have resurfaced, especially with the growing prominence of China in the global economy. In addition to the fear that ByteDance is “spying” on American TikTok users, some feel that China is spreading misinformation and propaganda through the platform.

Will the U.S. ever be able to successfully ban TikTok? The answer isn't so clear. Banning the app would exacerbate the sense of divide that Americans, especially younger, tech–savvy Americans, are feeling with their government leaders. When Congress questioned Shou Zi Chew on March 23, this divide was made even more obvious. People posted clips from the hearing, horrified at Congress members who were asking Chew questions like “Does TikTok access the home Wi–Fi network?” Chou responded that they “do not do anything that is beyond industry norms.” The questioning even elicited fan edits in support of Chew.

Congress members also continued to ask Chew questions about China and the Chinese government. Chew explained that although TikTok is owned by a Chinese company, he himself is from Singapore and TikTok’s headquarters were located in Singapore and the U.S. The Yellow Peril extends by default to other Asian ethnicities: Congress members seem to group everyone together.

On the other side, Congressman Jamaal Bowman, one of few Congress members who uses TikTok, called the attempt to ban TikTok “part of an anti–China ‘hysteria.’”

All social media apps have the potential danger of sharing users’ information, but only Chinese companies have faced severe scrutiny to this extent. Take, for example, the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal. The U.K.’s Information Commissioner’s Office found that Facebook’s lack of security had allowed the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica to gain access to up to 87 million people worldwide.

Facebook paid $643,000 in fines but never admitted any guilt. A couple months later, it seemed like everyone forgot. Facebook, now Meta, is thriving as ever, and there was no talk about potentially banning Facebook. These two instances paint a clear picture of Sinophobia in U.S. offices of power. Lawmakers will also face challenges bringing this TikTok ban on First Amendment grounds. Especially due to TikTok's expansive reach and the number of prominent individuals on the app, banning it could be seen as a ban of free speech.

The only difference between TikTok and other social media apps is ownership. Supporters of the ban have created a fear–mongering rhetoric based on Sinophobia, and the roots of this attempt reek clearly of “Yellow Peril.” While the latest attempt to fast track a ban was blocked, the consequences of Yellow Peril will continue to live on unless we actively work against it.