Wes Anderson loves stories. He loves stories about stories. He even loves stories about stories about stories. With his three latest films, The French Dispatch, Asteroid City, and the recently released collection of short films, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Anderson has delved deeper into his fascination with storytelling and created an unofficial “artifice trilogy,” three films that explore why we tell stories and how we frame them.

Structured like an issue of The New Yorker, The French Dispatch reflects Anderson’s love for the publication in three distinct but thematically related stories about a jailed painter, a student uprising, and a food journalist. While Anderson has always deployed some level of dry knowingness in his past films (like the storybook framing of The Royal Tenenbaums), The French Dispatch is the first to use such an explicit “story within a story” structure.

All three segments present a faux New Yorker story that would be the stuff of legend if they were real. In this way, Anderson is playing with the idea of myth–making and examining how a story becomes canonized. For example, the middle segment of the film is clearly riffing on the May 68 protests. Anderson heightens and exaggerates the event, inserting Timothée Chalamet as a student leader and Frances McDormand as the journalist covering and maybe falling in love with him.

Yet the intentional exaggeration works to further Anderson's point about storytelling. Widely regarded as one of the more important events of the 20th century, the May 68 Protests have been mythified to the point that the event no longer feels real. For Anderson, the only way to convey that is to make his rendition of the history so outrageous and ridiculous that it seems obviously fake. The very process of mythification fascinates Anderson and permeates the entire film, as he smartly zeroes in on The New Yorker as the publication that, more than any other, canonized stories of artists and revolutionaries in the 20th century.

Earlier this year, Anderson’s eleventh feature film, Asteroid City, again uses the theme of artifice to explore our place in the universe. While by far the most structurally complex film of Anderson’s career, featuring a play within a TV show within a film, Asteroid City is also Anderson’s most emotionally simple film. The nesting structure of the movie allows actors to play multiple roles, as both actors behind the scenes of the play and actual characters within the play (that is about a small town’s encounter with an alien). Through all the artifice and multiple layers of storytelling, Asteroid City explores how we use stories to process grief.

In the play within the film, Jason Schwartzman plays Augie Steenbeck, a grieving husband who can’t find the right time to tell his children that their mother has passed away. At the same time, we see Schwartzman as Jones Hall, the actor playing Steenbeck in the fictional play trying to understand the character, the story being told, and life itself. Anderson uses the many layers of story in Asteroid City to convey the complexity of life, and posits that only through creativity and storytelling can we process our finite place in the infinite universe. If The French Dispatch is about how stories are canonized, Asteroid City is about why we tell stories in the first place.

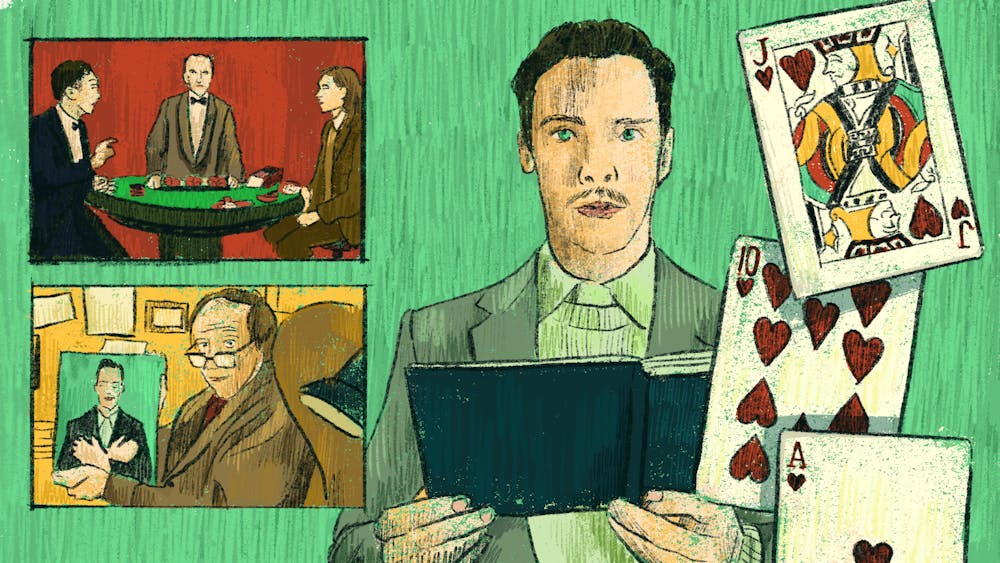

This brings us to Anderson’s latest project, a series of four short films. Each short, ranging from fifteen to forty minutes in length, deploys a cast of six main actors (Benedict Cumberbatch, Dev Patel, Ralph Fiennes, Ben Kingsley, Rupert Friend, and Richard Ayoade), each playing multiple parts, to tell four unconnected and lesser known Roald Dahl stories: The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, The Swan, The Rat Catcher, and Poison. Though filled with his usual scrumptious production design and visually stunning cinematography, these shorts have adapted Dahl’s works in a highly innovative manner.

In each short, Ralph Fiennes plays Dahl himself, sitting in his office writing the story. For most of its runtime, the actors recite the text of the short story verbatim to camera and only move around various sets constructed by Anderson—situating the short on the border between a film and a filmed play. Each short also ends with a title card revealing where and when Dahl wrote each of these stories, and a bit about what inspired him to do so. If all of this artifice isn’t enough, the longest of the shorts, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, features a “story–within–a–story–within–a–story” structure about a British bachelor, the titular Henry Sugar (Cumberbatch), who reads about a doctor who met a mystical circus performer long ago. The forty minute run time breezes by as the cast recite their lines of whimsical Dahl dialogue and walk through the best looking sets of the year.

The film shows Henry Sugar evolving from a flippant aristocrat to an introspective and philanthropic millionaire after learning the secrets of the circus performer. However, in the final minutes, we learn that Henry Sugar was just his pseudonym and that this story that we’ve just been watching has been relayed to Dahl by one of “Sugar’s” confidants in an effort to make his generosity known to the world while still protecting his identity. Through this very Dahlsian flourish, Anderson reveals his core point in making these shorts. All four stories are about misanthropic geniuses (Cumberbatch in The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Friend in The Swan, Fiennes in The Rat Catcher, and Kingsley in Poison) having a crisis of faith after experiencing an extraordinary event. It is as if Anderson, himself a somewhat misanthropic genius who is watching the world of film that he’s known and loved crumble around him, is taking the words right out of Schwartzman’s mouth from Asteroid City and asking, “Am I doing it right?”

By adapting four lesser–known Dahl texts and always emphasizing how and why Dahl wrote them, Anderson is saying that, in the end, stories are the only things we leave behind. Roald Dahl has been dead for thirty–three years, but we still know him because of the stories he told. Henry Sugar dies at the end of his story, but he will live on through the fictional story Dahl tells of him. The increased level of artifice in these shorts, therefore, is simply Anderson allowing Dahl’s stories to literally speak for themselves and showing that they will live on indefinitely. Great stories inspire future storytellers. Anderson, who has now adapted five Roald Dahl stories, including Fantastic Mr. Fox, was clearly inspired by Dahl to become one of this generation's greatest storytellers. And so in the final film of his “artifice trilogy,” Anderson uses the idea of storytelling to repay his debt to Dahl.

Wes Anderson has already signaled that his next film will be a departure from his recent work. If anything, it sounds like it will more closely resemble his earlier works like Bottle Rocket and Rushmore. If that is the case, then his “artifice trilogy” will remain as a unique period in his storied career—a weird, confusing, incredible, convoluted, seismic trilogy in the middle of one of the best current filmographies.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, The Swan, The Rat Catcher, and Poison are currently streaming on Netflix.