Time in South Korea moves fast. As quickly as Gangnam Style skyrocketed past the one billion view mark on YouTube, the Korean economy rallied from the trenches of a post-war depression into its current status as a G20 country. The nation has transformed into the highly urbanized culture and tech factory that we know today.

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s new exhibit The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989, artists of Korean heritage explore this revolutionary period in their country’s development. The exhibit, which is on view until Feb. 11, also tackles the concept of time, a complex subject given the peninsular country’s tendency to be on an accelerated timetable.

As soon as one enters the exhibit, they are confronted with an absurd spectacle that is Yeondoo Jung’s photograph Eulji Theater. A grinning man with a washboard is accompanied by swimsuits and North Korean army uniforms in the backdrop of the Haean Basin in the Demilitarized Zone while tourists watch him and the glorious landscape. The piece is deliberately surreal in nature, juxtaposing the humorous face of the man against the former battlefield of the civil war that occurred decades ago. Behind the grin that the work is centered on, Jung implies a future where Koreans are able to laugh in the face of their tumultuous history and move on from their shared trauma of the conflict.

Eulji Theater, 2019. Solvent printing with LED lightbox. 6 ft. 6 11/16 in. × 32 ft. 9 11/16 in. (2 × 10 m). Collection of the artist.

Yet, the next piece in the exhibit provides a more grim portrait of the time ahead. Forgetting Machines by Noh Suntag is a series of prints depicting the funerary photographs of the many lost lives of the protestors at the Gwangju Massacre. Many of the pictures are washed out, destroyed, and unrecognizable due to the hands of time. Even in death, their voices are silenced and a symbol of their remembrance—funeral photographs—are eventually rendered useless. Just around the corner, Juree Kim explores a similar theme of decay in Evanescent Landscape. Kim’s expert sculpture outlines the neighborhood of Hwigyeong-dong in Seoul, but it’s a sculpture that is meant to be destroyed. The clay that makes up the bricks of the houses in the work defigure at the touch of water, and over the course of the exhibition, puddles will begin to form and send the model of the town into ruin. It’s a metaphor for the rapid urbanization and apartment development that Korea is going through. As the homes crumble down in favor of high-rise buildings, so do the lives and memories of its inhabitants. In these works, Noh and Kim highlight the constant transience in Korean society that disregards everything in its path.

Eulji Theater, 2019.Solvent printing with LED lightbox. 6 ft. 6 11/16 in. × 32 ft. 9 11/16 in. (2 × 10 m). Collection of the artist

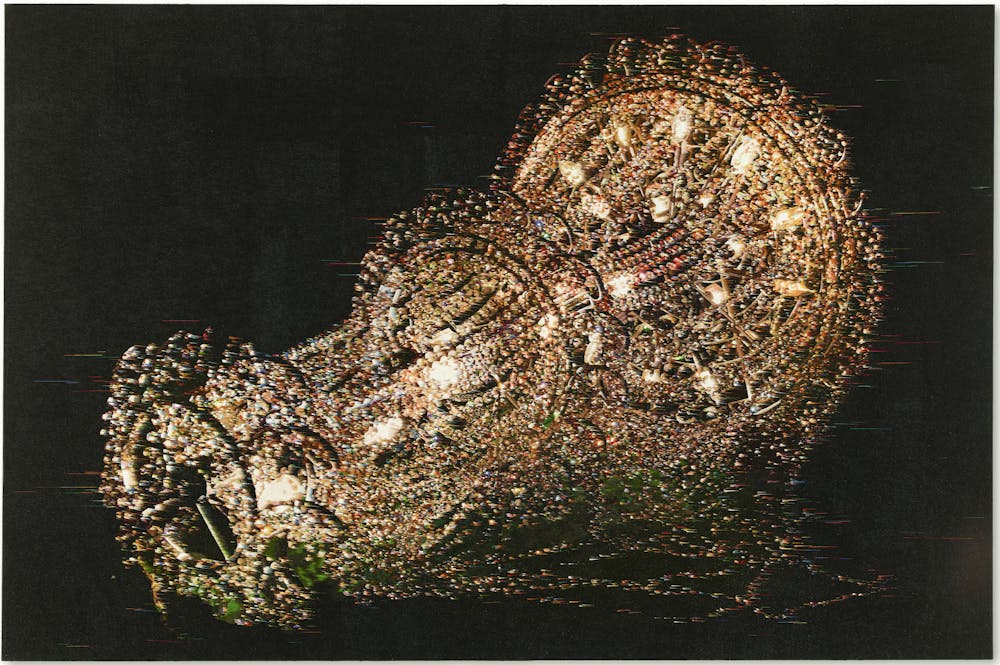

Just down the hall lies what I feel is the aesthetic centerpiece of the exhibit: a pair of tapestries from What You See is the Unseen by Kyungah Ham and anonymous North Korean collaborators. Ham likens the creation of this work to “a spy movie,” saying that she and her collaborators had to painstakingly smuggle images and texts over state boundaries to complete this project.

The resulting product is ethereal. The stitches blend into a crowd of faces that make their presence felt by watching the viewer as soon as they enter the room. Up close, the tiny strokes of silk that make up a 2-D chandelier radiate a transcendence that shines out against the background’s black chasm. Ham explains that these intricate details are supposed to represent uncertainty. In doing so, she frames Korea’s tumultuous course that began under foreign influence during the Cold War as nothing less than glorious. Unlike her colleagues in the museum, Ham embraces change and is eager to face whatever problems Korea may face in the future.

What you see is the unseen / Chandeliers for Five Cities, 2015-2019. North Korean hand embroidery, silk threads on cotton, middleman, smuggling, bribe, tension, anxiety, censorship, ideology, wooden frame, approx. 1650 hrs./2 persons; approx. 70 7/8 × 106 11/16 in. (180 × 271 cm)

In this curated space, artists capture the essence of a country that moves forward with both the weight of its past and the promise of an uncertain future. The exhibit becomes a reflection not only of Korean art but a window into the collective soul of a nation that will continually lose and gain pieces of its identity against the relentless march of time.