In her second feature film, Saltburn, Emerald Fennell, Oscar–winning director of Promising Young Women, sought to create a film that evokes physical reactions from the audience.

Set in 2006, Saltburn follows Oxford student Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan of The Banshees of Inisherin) as he pursues a friendship with the wealthy and alluring Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi). Oliver’s tragic past and his status as a scholarship student immediately brand him as an outsider. After a series of events (a flat bike tire, forgotten hookups, and several rounds of shots), Felix invites Oliver for the summer to his family’s exuberant English estate titled "Saltburn." From then on, however, secrets are revealed and chaos ensues. Street attended a roundtable with Emerald Fennell where she told us the secrets behind those secrets.

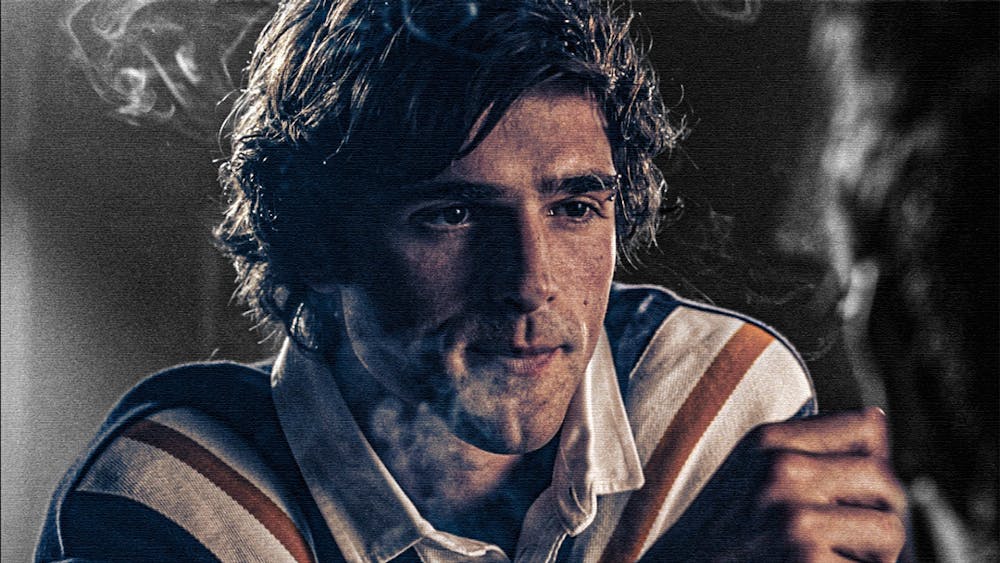

The grandeur of the Saltburn estate immediately overwhelms its audience and is further accentuated by the impeccable cinematography. Sweeping shots showcase the vastness emphasized by rich, saturated colors. The camera's graininess creates a sense of surrealness, as if the estate's beauty only exists in a haze. This lush style of filming is present throughout the film, especially when the camera approaches Felix. Slow, languid shots of him are often bathed in soft, diffused lighting. When Felix is in the frame, no space is wasted on anything other than his body and presence.

When casting for Saltburn, Fennell already knew who she wanted to choose to fill the god–like aura of the film: Euphoria’s Elordi. He occupies our mind and the screen in spite of his subdued manner, a sharp contrast from Elordi’s character in Euphoria. Yet, despite Oliver’s fascination with Felix, Fennell claims that “the idea of Felix is so seductive, but he himself is much, much less interesting than Oliver.”

Oliver, on the contrary, is someone who is constantly trying to dramatize his life and actions to capture Felix’s attention. While it is Felix’s uninterested demeanor that makes him feel so alluring to Oliver, it is actually the fantasy that Oliver constructs surrounding Felix that makes Oliver the more complex character. Regarding their relationship, Fennel explains that “in essence, the film is about the tension and desire between the two, and what happens to you when you cannot touch the thing you want to touch.”

Once inside Saltburn, we meet Felix’s wealthy parents (Rosamund Pike and Richard E. Grant), and his younger sister (Alison Oliver). The juxtaposition between their obliviousness to the outside world and the intensity of the events that transpire yield the funniest lines at the goriest points of the film. For me, these scenes left me guffawing while viewing the film through my fingers.

Sex is another prominent aspect of Saltburn. Sex is a difficult topic to straddle, as each audience member has a different tolerance on what is too much, what is too indulgent, and what is meaningful. The conundrum, however, doesn’t faze Fennell: “Some people are annoyed. Some people don't get it. Some people are laughing, some people are laughing with embarrassment, some people are squirming, and some people are turned on. And then, at one point, the audience kind of starts to turn on itself, because everyone thinks that everyone else's response is crazy and wrong.”

Thus, she doesn’t mind the unpredictability in audience reaction. This mindset is most present with regards to Fennell's perspective surrounding sex scenes, notoriously a dividing feature in a film. She states that she has a commitment to developing sex scenes that are not “gratuitous nudity that feels exploitative.” Fennell’s focus is on capturing all the intimacy and complexity that come with love and desire. “The sex scenes in this film are devastating, sexy, and interesting. Love stuff, you know, is not necessarily straightforward.”

It is the constant tension between multiple facets of Saltburn that makes it so engrossing. The beauty of the settings and the graphic events that unfold, the chemistry among the leads, and the tension between the filmmaker and the audience all culminate in an unmistakably entertaining film. To Fennell, this is what making a movie is all about, as she aptly points out that the film “is for people to not necessarily know how they're supposed to physically or emotionally respond to something and not be told they have to decide for themselves.”

During the roundtable, Fennell perfectly summarized how it felt to watch this movie in theaters. We gasped, laughed, sighed at different times in various intensities. However, the one constant is that we all reacted. As for me, I responded with a thrill and appreciation towards a director willing to push the boundaries of camp, beauty, love, and gore.