Bangs are riddled with personal histories. Some of us shudder at the pictures of old middle–school hairdos, while others have had to book emergency hair salon appointments over more recent late–night life epiphanies that did not, in fact, result in a new you, but instead a new task of cleaning the bathroom. Yet, regardless of our own knotted hair histories with bangs, there is no denying that we love them. They flatteringly frame our own faces, adorn our idols, and are almost always the feature in our favorite coming–of–age movies. However, the history behind curtain bangs, one of our favorite hairstyles, and their role in activism and politics is certainly more difficult to untangle.

Adored for their versatility and effortless elegance, curtain bangs have already become a staple in the 2024 hair catalog. The look is sported by notable celebrities and music artists including Sabrina Carpenter and Jennifer Lopez. Additionally, its rise in popularity can also be correlated with a general sense of nostalgia and turn towards vintage styles in the rise of a fashion world dominated by short–lived trends and fast–fashion controversies. And the side–swept nature of the curtain bang can provide a lower–risk alternative to a straight bang, since they are easier to grow out.

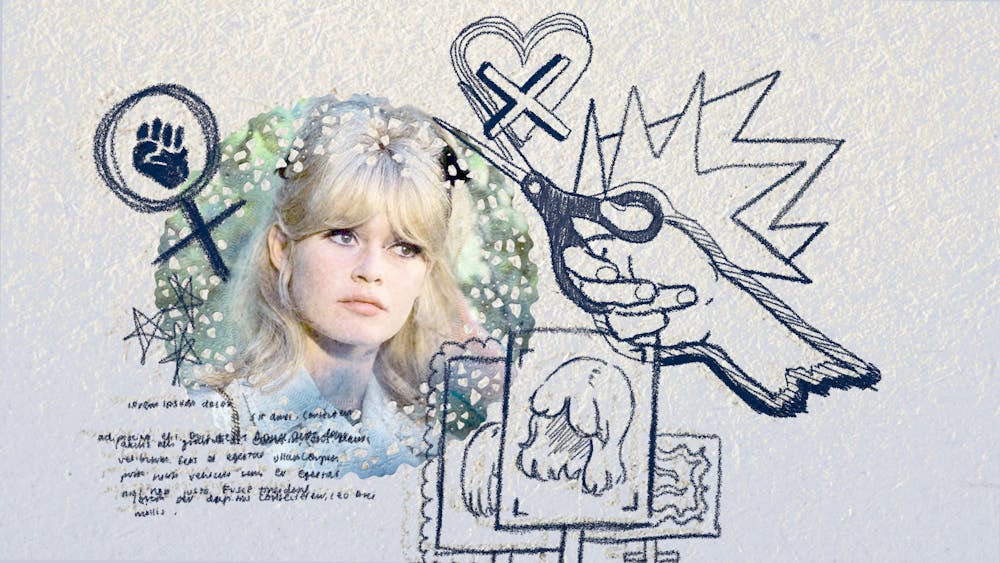

The curtain bang rose to stardom in the 1960s as the go–to hairstyle for the ever–controversial and adored French actress, Brigitte Bardot. In 1950, Bardot appeared in Elle magazine, starting her career at the young age of 15. At this time, she was the reflection of her upper–class, traditional upbringing, the epitome of Catholic grace and demureness. Yet, by the end of the 1950s, the image of that pristine girl was as good as dead.

In her short–lived film career, Bardot explored and embraced the subversion of many feminine expectations. She is even responsible for popularizing the bikini at the 1953 Cannes music festival. Outside of the spotlight, however, Bardot’s lifestyle was even more confounding to the bourgeois norm. Her divisiveness primarily stemmed from her display of sexual freedom; she reportedly had over 100 lovers, which included women.

Though she did marry—four times—and have a child, Bardot never embraced her role as either a wife or mother. She “behaved in her private life just like a man,” a reporter for the Guardian said. She dumbfounded the industry with a level of unabashed personal freedom of expression that was completely atypical for mid–20th century culture, let alone women in the 1950s. No physical manifestation of this freedom, however, was as influential or controversial as her hairstyle: the curtain bang.

Bardot’s hair was yet another way she subverted her orthodox upbringing. She opted for voluminous bangs and untamed layers, which contrasted the more prim, manicured styles that characterized the 1950s. As an icon of youthful rebellion for those exploring alternatives to the mainstream culture, Bardot also posed a threat to the status quo maintained by older French generations. Across the world, the infamous sex symbol was defamed as an “immoral,... egocentric child.” There were even movements to “ban Bardot” as she gained popularity in the US.

Although she would leave the entertainment industry in 1973 at the height of her fame to pursue animal–rights activism, her Bardot's signature hairdo wasn't inherently revolutionary. But it didn’t need to be; The person who wore them herself was antithetical to the stringent cultural guidelines in place at the time and thus they became symbolic of the shockwaves she sent through pop culture.

The impact of the aptly named “Bardot bangs,” is a symptom of a much larger phenomenon of seemingly deviant hairstyles being politicized. Hair is one of the foremost, physical means of expressing personal identity. Whether for intrinsic traits like natural texture or extrinsic ones like dyed color, the ability to express ourselves through our hair is empowering. But when that freedom is limited, however, the regulation of hair expression can also become a tool of oppression, because it can indirectly suppress other more implicit facets of our identity, like race or sexuality.

Just as Bardot’s hairstyle became a means to attack her sexual freedom, afro–textured hair has become a source of Black discrimination in the workplace. The 2023 CROWN Workplace Research Study, commissioned by Dove and LinkedIn, surveyed female–identifying adults of various races. They found that Black women’s hair was two–and–a–half times more likely to be considered unprofessional and that 25% of Black women believed that they were denied a job due to their natural hair. As of June 2023, only 23 states have passed legislation to end hair discrimination in the workplace. Just as attacks on Bardot’s hairstyle were direct affronts to her femininity and maturity, texturism and hair discrimination send a harmful message that aspects of racial or cultural heritage are undesired and need to be changed.

Curtain bangs might still carry the rebellious and carefree connotations that link them to the teenage actress of the 1950s, but thanks to ever–changing popular culture they are no longer judged or rebuked as a radical, undesired defiance of the norm. Yet many still struggle with discrimination because of their natural hair or hair choices. It’s unfortunate that such an integral expression of identity is still judged as viciously as it was 70 years ago.

Hair can be a political statement, but it shouldn’t have to be. Everyone should be able to express themselves through this medium without worrying about being persecuted for looking unprofessional or distracting. While it may no longer be divisive to go to a salon and get curtain bangs, a perm, or hair dye, it's evident that we have a long way to go until hair really is just hair for everyone.