Last Friday, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) opened its two latest exhibits for the fall: Ree Morton: The Plant That Heals May Also Poison and Cauleen Smith: Give It or Leave It. Both open through December 23, the two, at first, seem like an eclectic collection of miscellaneous art pieces and sundry objects. And maybe, it is so. The exhibits are not bound by their creative content, but rather are threaded together by their underlying themes of openness and expansiveness.

Stepping into Morton’s first retrospective since her passing in 1977, the viewer is greeted by what at first looks like a banner. Looking closer, it’s five lightbulbs, enamel and glitter on wood and celastic. Sprawled across the wood reads: “The Plant That Heals May Also Poison,” with the ribbons of celastic listing five words, “Cyclamen,” “Nightshade,” “Hellebore,” “Aconite,” and “Jamestown Weed.” All plants that heal, but once delivered in a certain dosage, also poison.

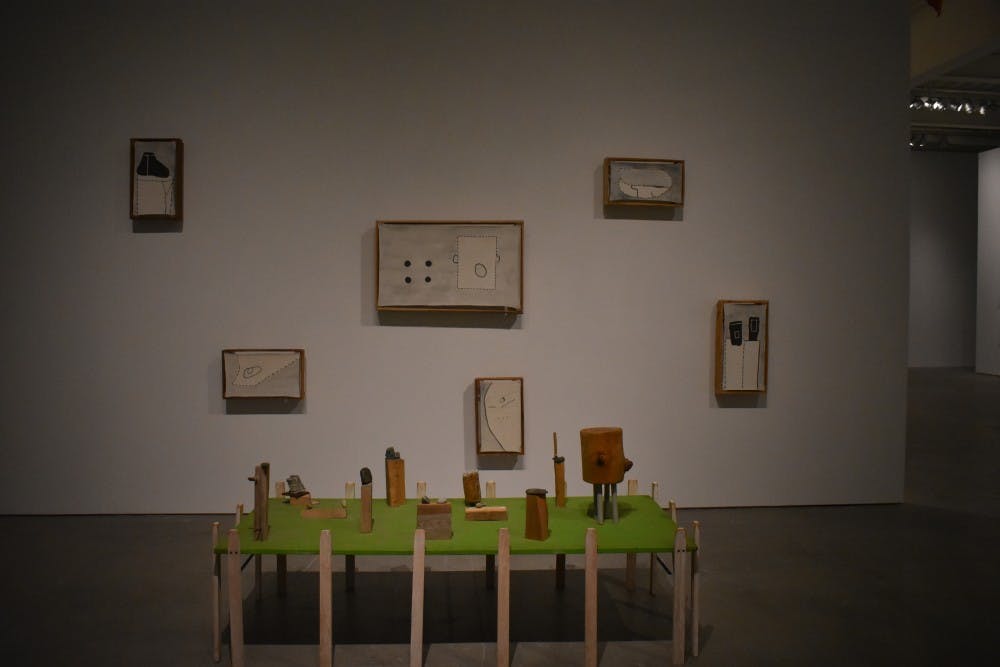

In the rooms that follow are more than 40 other works by Morton. There’s “Be a Place, Place an Image, Imagine a Poem,” which consists of a table standing on its wooden legs, with more wooden blocks on top. There’s “Signs of Love,” a wall with two colorful ladders leaning against it, ribbons draped across it, and a checkered tile with two swans in the middle. There’s “Manipulation of the Organic,” Morton’s final completed work and a room of paintings showing the growth and change of something natural.

Walking through the exhibit, it feels a lot like empty space. This is because of Morton’s association with the Postminimalism movement, a general reaction in the late '60s against Minimalism and its strict adherence to closed, geometric forms. The Postminimalists saw more open forms as a medium–hence the openness of many pieces in the exhibit.

While the exhibit is multidimensional in nature, once seen together, The Plant That Heals May Also Poison is a collective singular of Morton’s interpretation of love, domesticity, childhood, and maternity. In many ways, it’s not an autobiographical tale, but rather, a show of how she understood her own life. At age 25, Morton already had three children. However, as it was during the '60s for women, the choice came down to her family and her career. In an interview in 1974, she said, “I still wasn’t able to call myself an artist. I was a mother, I had children, I had a family to take care of.” So she chose her career. She sent her children to live with their father—a difficult decision, no doubt, and by no means an indication of complete abdication of her role as a mother as expressed in “Signs of Love.”

Though largely influential in the movement, Morton’s legacy has hardly been recognized. “This exhibition marks the first time in generations that audiences in Philadelphia and from across the U.S. will have an opportunity to experience the captivating and innovative work of Ree Morton,” said Amy Sadao, the Director of the ICA. “The Plant That Heals May Also Poison reflects our commitment to illuminating the pioneering work of under–recognized artists whose work merit reappraisal and placing them within a new, contemporary context.”

The next exhibit by Cauleen Smith takes the viewer up the stairs of the ICA, where the first stop is a dark room, with a film projected onto a screen. Strung across the ceiling is another banner, reading “I appreciate you in advance,” with its shadows magnified onto the wall. The black lettering set against the red background gives an eerie feeling, one counter to the message.

In essence, the exhibit is a journey across four universes: “Alice Coltran and her ashram, a 1966 photo shoot by Bill Ray at Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, Noah Purifoy and his desert assemblages, and black spiritualist Rebecca Cox Jackson and her Shaker community.” All of these are references to spiritual sites embodying a mutual generosity shared between the artist and community. The very title of the exhibit, Give It or Leave It, points to this theme. A play on the normal “take it or leave it,” Smith posits a more positive attitude revolving around giving rather than merely taking.

Each of the four rooms of the exhibit are remakes of the four universes. In the second room, one wall is a simultaneous projection of four different screens. One shows a storm; another, a walk through cherry blossoms; another, what looks to be an escape. Off–center is a round table, a fake moss covering it with a motley of seemingly unrelated objects: feathers, video cameras, books titled “How to Get Free.” They all point to an eventual freedom and liberation. One room past is another dark room, lit by a number of disco balls with another film screening—another universe. Here, a sign reads: “After the comfortable, comfort the afflicted.” Though representing four very different scenes, all of Smith’s works are tied together by the commonality of hope, optimism, and generosity.

Exhibits this Fall at the ICA run until the end of the semester. Admission is free for all, so don’t miss out!