The latest art exhibition at the Barnes Foundation is not an exhibition of an artist, per se.

“Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miró to Man Ray,” the first solo curation attempt by Barnes Foundation Associate Curator Cindy Kang, centers instead on the artistic influence of a French Depression–era entrepreneur, who commissioned rather than created much of the work that fills this exhibition’s galleries.

Cuttoli is a name that few know well, even in the art world. Coming from a provincial background with no significant education past the age of 16, she found a path to success not dissimilar to the majority of other famous women of the art world: she married rich.

The marriage would prove to be influential on more than her financial status, as her Algerian-born French politician husband Paul Cuttoli enticed her to frequent both Paris and the Algerian port city Phillippeville, where he built his new wife a luxurious villa called Dar Meriem.

With deeper pockets and broader exposure to French colonialism in North Africa, Cuttoli decided to open a fashion house and boutique in Paris called Myrbor—a name that references both her time in Algeria through the Arabic spelling of her name as Myriem, followed by the first three letters of her maiden name, Bordes.

The first room of the Barnes’ latest exhibition attempts to recreate the ambiance of Myrbor’s boutique, displaying both colorfully ornate evening jackets and modernist-style rugs designed by contemporary tapestry revivalist Jean Lurçat, foreshadowing Cuttoli’s later efforts in her own resurrection of French tapestry.

This first room exhibits Cuttoli’s ambition, personality, and artistic taste far better than the rooms that follow. Paired with old photographs of her boutique and its original decoration, this gallery underscores the modernist sensibility that would permeate the rest of Cuttoli’s career, even as she heavily embraced the role of commissioner in her later years. Lurçat rugs hang on the wall instead of resting on the floor, providing a backdrop to the brightly asymmetric patterns of the Myrbor jackets on display.

Together, the elements of this room attempt to establish a thread that the middle rooms of the exhibition somewhat abandon—that the art of decoration and style in the early 20th century had an inherent overlap with modern art, so much so that, in the case of Myrbor at least, one came to define the other. Or, as more succinctly put by Thérèse and Louise Bonney, “If you like to see a Léger or a Lurçat or a Picasso on your walls, you will like to wear Myrbor clothes.”

The following rooms of the exhibition seem to have one consistent aim in juxtaposing model paintings, referred to as cartoons in this context, and the tapestries designed after them. To witness the direct and dramatic back–and–forth examination that these galleries afford—of works by Georges Rouault, Georges Braque, and André Derain—is to enter another world entirely, one that feels notably distinct from that of Cuttoli in the first room. There is no denying the grandeur of the creations that crowd these galleries, and the magic in seeing them reproduced through different media and iterations, but there is also no denying that Cuttoli grows more and more absent from the exhibition named after her.

Instead, Cuttoli’s presence is behind the scenes, as a patron of Aubusson–originating tapestries in an effort to revive what she perceived to be a dying yet essential facet of French art. Stemming from her early interest in rugs, Cuttoli’s ambitions to revive the industries of the historic French town put her in more of a curatorial role than anything else. Though she most likely approved artist designs and certainly funded their translation into tapestry form, these galleries lose the engagement with the dual cultures of her homes or the tensions between cosmopolitan decoration and museum–intended art that the first gallery hinted.

Still, there are glimmers of Cuttoli interspersed among the mesmerizing dominance of tapestries designed by Picasso, Braque, and Man Ray. In a hallway toward the back of the exhibition is a tribute to Cuttoli’s friendship with the museum’s namesake, Dr. Albert Barnes, who gave her work as an artistic entrepreneur a great deal of attention and supported eventual exhibitions of her commissioned tapestries in the United States.

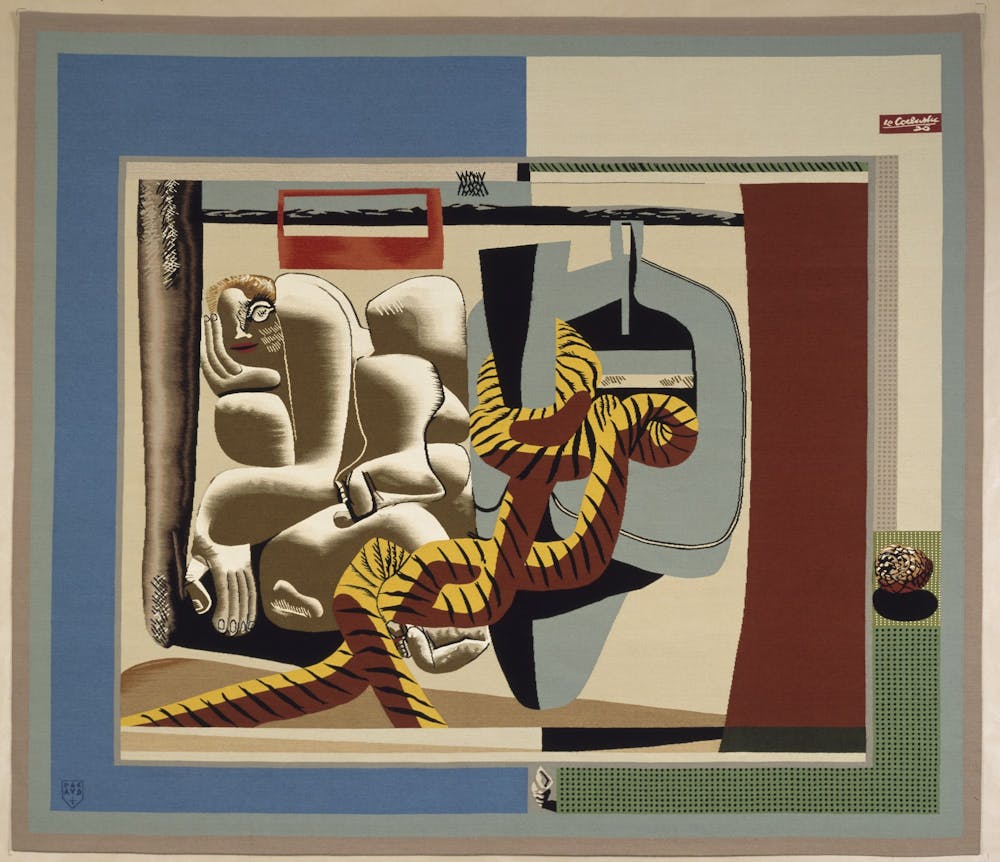

Beyond an assortment of telegrams, letters, and a recording of Dr. Barnes’ praise of Cuttoli in a radio address, we see her in one of the more captivating painting–tapestry pairings of the exhibition: a modern rendering of a figure, a boat, and a rope by Le Corbusier—an artist and architect who notoriously denied all unnecessary embellishment in his work. Titled Marie Cuttoli, this 1936 oil on cardboard cartoon suggests Le Corbusier’s own gratitude for Cuttoli’s contributions to the revival of tapestry, most likely because he saw its ties to mural art, of which he was a passionate fan.

His rendering of Cuttoli here wrestles with the same French colonialism that informed her work at Myrbor. The nude figure recalls Le Corbusier’s own earlier sketches from time spent in Algeria, while the boat and rope evoke provincial France. In squishing them together and snaking the rope around both the figure and the boat, Le Corbusier expresses some of the uncomfortable cultural compression evident in the markers of French colonialism that haunt the majority of modern art from this period.

Here is the last chance we have to really understand Cuttoli as more than a tastemaker or investor in the art of tapestry. What follows in the final gallery are masterpieces, including two vibrant Miró–designed tapestries, one of which is set up to be viewed from both its front and back sides. But the suggestion of the final gallery that Cuttoli’s contributions to the world of tapestry were one of the main forces in propelling modern art to mainstream audiences falters.

The latest in a series of rather provocative exhibitions by the Barnes Foundation will certainly leave its viewers amazed by the capabilities of the Aubusson tapestry masters, and thankful that Cuttoli had the wherewithal to revive it when she did, but it does little to plumb the depths of the entrepreneur's deeper motivations in doing so. Her evidenced proximity to these giants of modern art and their mutual respect for her in following through on commissioned tapestry designs tell a story that requires greater insight.

What’s needed is a more intense infusion of Cuttoli into each of the galleries—without it, she remains neither stranger nor friend to the show’s patrons, and many will no doubt leave forgetting the very woman that this exhibition tries to remember.

Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miro to Man Ray will run through May 10, 2020. Student tickets are $5.