Last August, during the thick of NSO, two white male students broke into another student’s apartment and refused to leave. The victim spoke on the condition of anonymity, but her story reveals a malignant societal truth that also infects campus life at Penn: white privilege exists unchecked.

She says the students were aggressive and visibly intoxicated. Penn police were called. Two officers arrived on the scene: a white woman, and a Black man. They handcuffed the two boys, one of whom was especially appalled and infuriated by this turn of events. He allegedly then began to spit racial slurs at the Black officer. “You don’t know who my father is,” he then told them both.

“You can’t arrest me,” witnesses heard him say, “I’m just a white boy.”

Seeking absolution, the student stated a claim that attempts to diminish and excuse the severity of his actions because of his youth and race. A report was filed and the students were escorted off the premises. No charges were pressed.

We often talk about the “Penn bubble”—how insular and sheltered life at Penn can be from the outside world. But this bubble, however, doesn’t shield Penn from the racism and white privilege in the communities that surround it. University City is among the most highly policed areas in Philadelphia, with five overlapping precincts empowering white students to feel safe weaponizing the color of their skin. While the events of last NSO were appalling, they weren’t surprising. Racism still exists and whiteness comes with an inherent social privilege.

The boy arrested in this story knew these truths. He attempted to capitalize on them and he perpetuated them. In fact, most people are aware—albeit subconsciously—of these truths. But, as exemplified by what happened a year ago, if one is not directly affected by the the plight or pain of another, their suffering is easier to dismiss.

The recent killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery—among countless others—at the hands of current and former police officers have been a wake–up call for many non–Black people, despite the fact that this alarm has been ringing for centuries. The brutality and viral nature of these events have highlighted a near–universal complacency to the Black plight and have publicized anti–Black racism in a way that makes it impossible to dismiss or ignore.

Ultimately, these recent injustices are a call to action. And many are eager to heed this call, recognizing the overwhelming need for change.

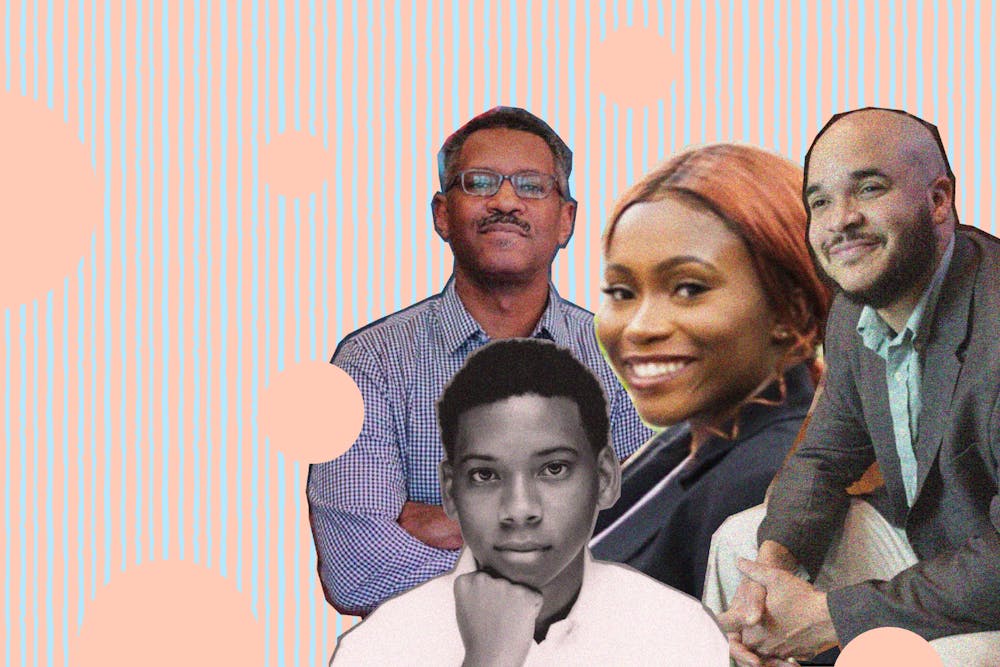

Penn’s current student body is 6.19% Black. 93.81% of today’s Penn students will therefore never experience anti–Black racism. But the 93.81% are faced with the following question: what does it mean to be an ally? In pursuit of an answer, Street sat down with four of Penn’s powerful Black voices to discuss allyship and how the Penn community can ensure that anti–racist activism endures, despite the historic transience of non–Black sympathy and the danger of ignorant apathy.

The Interviewees

Dr. Brian Peterson is currently director of Makuu: The Black Cultural Center and a professor of Africana Studies at Penn. He graduated from Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and then received his masters and doctorate from the Graduate School of Education. He is the author of four books and the founder of an academic and cultural enrichment program, Ase Academy.

Reverend Dr. Charles L. “Chaz” Howard is University Chaplain and Penn’s recently appointed first–ever Vice President for Social Equity and Community. He has written for publications such as Black Arts Quarterly, Black Theology, Sojourners Magazine, Christianity Today’s Leadership Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Huffington Post, and Slate. He is the editor of The Souls of Poor Folk, The Awe and The Awful, Black Theology as Mass Movement, and Pond River Ocean Rain. He has taught at Penn’s College of Arts and Sciences and in its Graduate School of Education, as well as at The Lutheran Theological Seminary of Philadelphia.

Kristen Ukeomah is a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences majoring in Health and Societies, concentrating in Health Policy and Law, with a minor in American Public Policy. Kristen has served on the Undergraduate Assembly's Social Justice committee, and currently is in her second year on Equity and Inclusion committee. Kristen is also engaged in increasing awareness of commonly undiagnosed disabilities through NSO programming and RA/GA training. Outside of the UA, she is president of the Black Student League, president of the Penn African Student Association, an Ase Academy mentor, a Weingarten Ambassador, and a PAVE Educator, among other roles on campus.

Chase Starks is a sophomore in the College of Arts and Sciences where he is majoring in Neuroscience and minoring in Consumer Psychology. He is a member of the Club Tennis Team and the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, and hails from from Atlanta, GA.

Editor’s note: Interviews have been edited and condensed for content and clarity.

Practicing Allyship

Eva Ingber: What does being an ally to the Black community look like to you?

Dr. Brian Peterson: In this moment in particular, the most important piece of allyship is being responsive and being able to take leadership from people who are on the front lines—specifically Black students or Black peers and Black activists—and really channeling their energy to have conversations with people and ask, “How can I help directly, how can I help indirectly?”

Particularly for Penn’s context, I would want that to be the way to move forward. But in many ways that’s a catch–22, because it places some burden on the Black student leaders to do the work. The real work is in terms of racial solidarity, which really is making America what it’s supposed to be: a multicultural space that respects everyone. That’s going to take all of us at the table. It’s not inviting people to the table, or saving seats for people at a table. It’s creating a new table where we’re all sitting down together, and having a conversation, and all respecting each other, and in that regard we’re all allies to each other. But we can’t skip to that step. Right now, we have to specifically address anti–Blackness in this moment because that’s what this movement is about.

Reverend Dr. Charles L. “Chaz” Howard: I think [allyship] allows for one to be in process. It’s a big ask to expect someone to fully understand the multiple layers and systems that contribute to 400 years of oppression. The point I would push would be that an ally can be one who is in the process of learning, growing, and understanding the many systems of oppression and the interpersonal aspects of racism and hate and fear and prejudice that come along with that, with the important nuance being the ability for an ally to be in proces: not fully a perfect ally, but certainly willing to try.

Kristen Ukeomah: I think that definition is holistic in the sense that allyship looks very different depending on your interactions. There’s a role non–Black people play as individuals and systemically. Everyone’s relationship with whiteness or with their white peers or non–Black peers is different. I think some people may want support. For example, a lot of people have expressed, especially with arguments around colorism and all the intersectional ways oppression occurs, that people appreciate when our privileged peers fight or advocate for us. The onus always falls on Black people.

The definition [of allyship] is broad enough because some people might prefer the advocacy, while some people prefer the amplification and prioritization of Black voices instead of [actions] done by non–Black people. As people, we’re always becoming more aware of what racism looks like. As a people, we’re evolving, and we’re realizing that there’s more wrong here than we realized before. As an ally, you should be able to evolve and not be held back by what Black people were satisfied with 50 years ago.

EI: Should being an ally look different for people of different races/ethnicities? Is there a universal code of action, or does it look different for each person?

CLH: Yes, I think it looks different for who the ally is, and I think it looks different for whom one is being an ally to. A different relationship might demand or call for a different type of allyship. Likewise, I do think that there is a potential for a different type of allyship within people of color. On campus, that’s expressed well. I think the folks who are LGBTQ are different types of allies with one another than other people on campus, and I think it’s all with the same goal. But there’s different history there, there’s different shared history, there’s different shared sections of oppression, all obviously not all the same.

There’s different levels of understanding, and there’s an important nuance to make. Being an ally to a Black classmate at Penn is different in some ways than being an ally to folks who are in Minneapolis right now. Being an ally to someone in West Philly is potentially different than being an ally to someone in Sudan. It’s important for an ally to understand that.

Chase Starks: There shouldn’t be a stigma or a difference between a person of a different race being an ally, but I do definitely think there is a stigma out there, because certain races are seen as more eligible to be allies. In actuality, it shouldn’t matter what race you are—an ally can be anyone. Just because you're posting doesn't mean you're having as much impact. You can sign petitions, you can keep your friends in check or support them, so I don't think there is a universal way. Everyone has their own impact and their own set of things that they can do.

The Penn Problem

EI: Can you talk a bit about what privilege and racism might look like on campus?

BP: All of us who have been educated in American history from a white supremacist lens have all been privileged by ignorance. It’s an awkward way of saying it; it just goes to show that there have always been these two ideas in America: the idea of America that exists right now in people’s minds is this idea of freedom and equality, where everyone has access to the same rights. So, when Black people aren’t doing something, it’s because they’re lazy, or when Black people are arrested more, it’s because they’re criminals—not that there is a policy in place that overpolices their neighborhoods and underpolices a place like Penn that may have the same level of narcotics activity. But no one is getting arrested at Penn for narcotics.

Those are the kinds of things that if you take off that veil, that privilege of ignorance, and really ask yourself these kinds of questions, you begin to say, “Wait, there are things that have been happening all around me that have never impacted my life as directly as they may have impacted someone else’s life, and I should spend some time thinking about that and thinking about what can I do to change that.”

CLH: I think there are two ways of looking at it. I think that there's the privilege of not having to experience certain aspects of hate and prejudice, or being forgotten, or being marginalized. The other aspect of privilege—and I think this is something I see very often in the world—is the privilege of not having to care. And it's connected to the great conversation we're having in America right now about the difference between not being racist and being an anti–racist. There are a lot of our students, faculty, and staff who aren't racist people, yet don't necessarily have skin in the game and aren't anti–racist. That's an aspect of privilege, where one doesn't have to be in this fight.

KU: Systemically, how Du Bois is becoming a whiter dorm is very interesting to me. I think it’s racist, honestly, to not honor the importance of a Black space. I was looking at other schools that have similar programs, or similar Black residential programs, and if there's a non–Black person living in this dorm they may be taking an African language or they are majoring in an Africana study: they have some sort of tie to Blackness at least, so it’s not random.

In addition, I would say even on Locust, Black students—this is a microaggression—are expected to move out of the way for their white peers. We’re expected to move, and because we do it subconsciously, we just get out of the way. But if we don't get out of the way, we tend to hit someone because they expect us to move, and by the time we’re not moving, it's too late and they hit us. It’s very subconscious, and some people don't even realize that. It's also conditioning for Black people as well, as if we’re expected to move out of the way.

Black students on campus hang around each other not even because we dislike white people but because we find solidarity and safety in our community. Parties are a part of the college experience that contributes to how you enjoy Penn, and if I can't go to parties because I don't know people, because I'm a Black student and I just didn't get to meet them, I'm missing out—the only opportunities we get are Black parties. It's also irritating as a Black woman to see white women get in so effortlessly when we have to beg to get into their party. It's an interesting feeling, like we can’t fit into certain clubs. Even though I'm on UA, me being in the Black Students League and the Penn African Students Association is, honestly, because those are the only clubs I felt like I actually had a chance of winning or being able to succeed in.

EI: I think a lot of non–Black people—and I include myself in this statement—are eager to be allies but are nervous about asking stupid questions or saying something unintentionally hurtful, and are aware that it isn’t nor should it be the job of the Black community to educate us. How can we go about asking questions and being allies in a way that is sensitive to this reality?

CLH: Just the way you phrased it right there: naming the tension. The emails and messages that we are appreciated the most are, “Dude, I can only imagine how heavy this moment is for you, and you’re busy and being pulled in a lot of different directions—yet if you're open to it, I’d love to have a conversation. [But] if it's not a good time, totally fine.” Or when people have said, “It's a lot to ask from you, my Black friend, to help participate in repairing brokenness in the world when a lot of Black people are experiencing brokenness themselves, and yet I want to offer the invitation to.” To me, I think that's the [best] way.

I've seen the range of reactions here, white colleagues, allies, asking, “How can I help? How can you teach me?” And there's something beautiful about the willingness to learn and willingness to serve, yet there's a deep exhaustion that I've felt, and I think other Black people have felt, around the call to be teachers to our white peers and colleagues—making us do the work of fixing the world when we didn’t break it.

KU: It’s honestly hard to navigate. I, as a straight woman trying to understand the queer community, found it helpful to just listen and hear the complaints and concerns of their community without inserting my voice. I try to, instead of asking questions, see if there’s an answer that already exists and then if it doesn't make sense or is contradictory, then I would ask someone I know—like a friend, because there's a standard that exists as a friend; it’s okay to ask them questions versus asking that random Black person a question, or a random queer person a question. I’m most likely going to be wrong, as a human being it's likely I have been wrong multiple times. It's important for me to acknowledge that, apologize to the people I've hurt, and move on.

EI: There are countless resources available for aspiring allies to turn to as means for education, but do you have any suggestions specifically for Penn students to help learn more about the Black community and become better allies?

CLH: I think your peers are the best resources, or at least as good a resource as reading White Fragility or How to Be an Antiracist or watching the movie The 13th or Just Mercy. To me, those are introductory spots. If one really wants to do the work, you dive in a little deeper into bell hooks, for example, or some sort of next–level critical assessment of history and what's going on in our country. Learn about critical race theory. Take a class in Africana, or minor in Africana, or major in Africana, for that matter. Visit Makuu. Visit Du Bois. Visit the African American Resource Center. Visit Africana Studies.

It's not a perfect parallel, these are different histories in different contexts, but in the last several years we've had a real uptick in anti–Semitism. If you replace the question around how can one be a better ally to our Jewish classmates and neighbors, [there is] a similar answer. You would read books, there are movies one could watch, one could visit Hillel, one could visit Chabad, one could talk to the friends that they feel close to and say, “Hey, I know this is a lot to ask, and if it's not a good time, I get it—can you tell me like what you think, and where you are on all this? And I recognize that you're not the spokesperson for Jewry around the world...but if you're willing to share, I'm willing to learn and listen.”

And I wonder if that's sort of a way to paint a picture of what it means to be an ally: whatever corner in the world one inhabits, there's a potential for [one] to experience hate, oppression and fear. What would you want? How would you want someone to be an ally to you? Whether it's any Asian person who felt some of the cruelty experienced during the [pandemic] that are still going through, whether it was after 9/11 and people who were Muslim, or presumed to be Muslim, experienced. Whether someone is queer [in the midst of the] perpetual homophobia that the world has.

What would you want in an ally? How would you invite someone to learn and journey with you? And I think to spin that around and say, "Maybe I could try and employ some of the same techniques in being an ally to the Black community right now." Again, different context, different history, different moment in the world, different administration here in the country, all that—but I think it could be a bit of a map toward where to go.

KU: Just learn—educate yourself. As a Penn student, it means taking a sociology class or an Africana studies class, emailing professors...I really appreciate it when people in privileged positions do a lot of the heavy lifting for you. There are white people that are also “woke”—use their labor, honestly. You may have a friend or a more knowledgeable person that understands this relatively well. There are white sociology professors. There are white Ph.D. students in Africana. Have a white Ph.D. student in Africana talk about their experience with privilege and how other white students can “decolonize” their minds. This is not the labor of Black people, you know? And I think a lot of the things that are being said right now have been said for a long time, they're just now reaching white ears. So to add more clarification is honestly just putting more work [on Black people]. The goal for non–Black students at Penn is to find ways to be allies and learn more about this cause without causing Black students to do more heavy lifting for you.

Optics of Allyship

EI: Social media has played a big role in advocacy these days, and has served as a platform for so many to speak out against injustice. A lot of non–Black people have turned to posting as a form of allyship. Can you talk a little bit about performative and optical allyship versus non–optical allyship? How can people be sure they’re not just being performative? And how should people go beyond social media?

BP: I think it's easy to give likes and shares, but did you read it? Did you think about it? Did you reflect? People may not want to go to a protest just out of fear of coronavirus. Or people may not even have a statement they feel comfortable sharing, so then they like a bunch of stuff, or people craft a statement so they can feel like they’re participating in the posting. I would say you definitely want to continue educating yourself, because there's so much that we haven't learned. I would push people to really read these pieces, think about them, talk to people and then think clearly about where they observe the things that are being written about in these pieces, and what is their action plan and then practice putting that in motion.

KU: I think performative activism is based on whether you're doing things for an audience and comparing yourself to other people and what they're doing, versus the impact you're making. I’d prefer if people were donating to causes—I know it’s hard for people to find legitimate causes to donate to sometimes—but as the phrase goes, I'd rather people “open their purses” and just donate or support Black students.

Let’s say you might not have as much money on you right now, but when we get back to campus, how are you gonna help Black organizations? We don't have the ability to throw parties the way white students do. My white peers have three formals a semester, you know? And it's not that that's bad—that’s the goal. Yet we don't have the resources to pay that, so they should be sharing resources.That’s the kind of activism I prefer [more] than black squares, because you didn't have to donate to anyone, you didn’t lose anything. If anything, you just lost followers if they didn't agree. I've often thought that the biggest changes with this have been monetary. I really appreciate institutes donating money to causes as opposed to just their sentiments and their feelings and their emails. I think that's the way I discern performative activism, like who did you do this for? What was the effect on Black people specifically?

CS: A lot of people are just posting for blackout. And I think it's very dangerous to get caught up in performative activism, because when people just start doing that, then its actually [dangerous] to the movement. In general, it's nice to take that extra step and not only just post to get the word out. Sign a couple petitions, you know? Keep your friends in check, like I said, [asking around] if you don't understand a certain topic or are confused. Knowledge and information just actually help so much more than just simply posting for self–satisfaction and then forgetting about it, because a lot of people are forgetting that this is not just a trend, it's a movement, because we’re trying to save an underrepresented group of people who are very oppressed in society.

EI: Do you think all allies should be vocal on a public platform of some sort—that they should all be posting on social media, like Instagram or Twitter?

CLH: Nah. It's not everybody's lane. I know a lot of people who just don't do social media for a range of reasons, and that's fine. But I do want you to do work where you are. It may be that when we get back to campus or when things sort of pick up, you're going to make sure your club is better, that your sorority is going to move the needle this year in a good way, that this a capella group or this college house is going to be better and we're going to look at ourselves and ask the question, "Why haven't there ever been Black officers in this club ever? Why are there no Black members?" To me, that is a form of allyship. A lot of people aren't about marching either—particularly in the age of COVID, but even before that. A lot of people aren't about going out and raising their fists and yelling and marching and taking over spaces. That's okay, but wherever you are, make your corner better.

KU: I love private activism. Honestly, I think that it's great as long as it's not small, you're still doing a lot of work in other ways. I can imagine potentially some people may not want to post because they are not a social media person. If Black students want to protest on campus, would you be willing to participate? Would you help us? That's private activism to me; you're not [posting on] social media, but you're willing to be at a protest. And you're willing to get arrested. That means a lot. If you're truly a private person, I get it, but do something. Please. Activism in the way that it counts.

CS: This goes back to your question about what is an ally—I personally think that you shouldn't feel pressure to post on social media; sometimes it's just not your thing. But you should at least spread the information about how you sign petitions. Not everyone has to post, it's a good way to get stuff out, but there's no single way to be an ally. As long as you're helping out.

Is This a Good Start?

EI: It feels like there’s so much change that needs to be done, and sometimes that can be overwhelming. Groups on campus seem to be doing a lot right now—petitioning, donating, et cetera—but do you feel like these smaller actions are enough?

KU: I just hope the activism continues on campus. It's honestly performative if white students care more about Black lives on social media than they do on campus. There are Black students here that are complaining about the grievances they experience not just at the hands of white administration and white professors, but even white students—what are you doing with those issues? It's not just about Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. There are Black students on your campus. How are you supporting them? That's where we’ll find out if our peers are doing enough.

CLH: It's a great question. We're not going to fix this this summer. I think to interpret what you said as, “Is this a good start?” And yeah, it’s not even such a good start—it’s a good continuation. You don't undo 400 years in 40 days. It's such a complicated web of oppression that needs to be undone, and a revision over so many different fronts. Rethinking racial concerns and racial needs on campus is a part of that, and sharing of our resources to different resources on and off campus is a part of that. Doing self–examination is a part of that.

But we have to look at the Philadelphia school system, policing in Philadelphia, elected officials, redlining, gerrymandering, health disparities, the way the history is taught...there's just so much of it. It's not enough, no. But it's a start. Our kids are going to continue this fight, too. It's going to be a lot better, but it's not going to be done by the time we close our eyes. So our challenge is to carry the baton for our leg of this race and to do a good job running—but we’re not finishing or fixing it, we’re just doing our best.