In 1953, Samuel Taylor wrote the play Sabrina Fair. The play's title is in reference to John Milton’s masque Comus. In ’54 it was made into a film by director Billy Wilder, and then remade by Sydney Pollack in ’95. Looking at the original script of the play and watching the two movies, it is remarkable how the dialogue required only a few changes. Aside from minor pop culture references, much of the remake appears to be identical to the original film. Many films from the past don’t hold up against today’s scrutiny, but the plot of Sabrina is enduring and perennially impactful. Nonetheless, when looking deeper at the storylines, the unique setting of each remake allows for more refined storytelling.

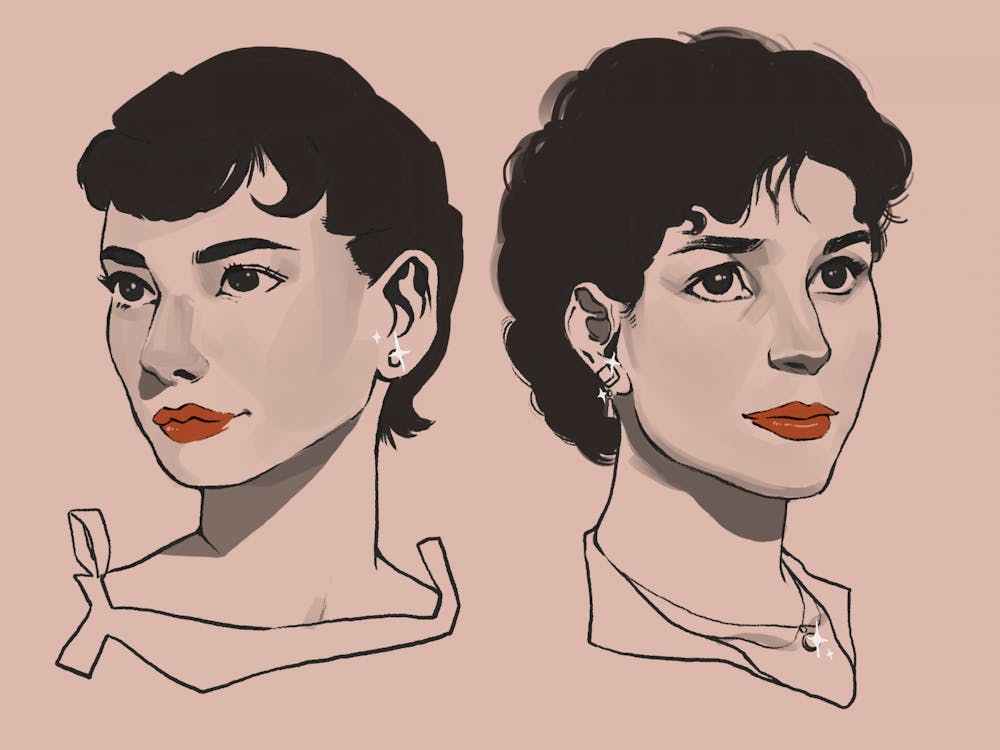

Sabrina tells the story of the titular young woman, the meek daughter of a chauffeur to the wealthy Larrabee family. The two Larrabee brothers Linus (Humphrey Bogart and Harrison Ford) and David (William Holden and Greg Kinnear) couldn’t be more different. While Linus is known for his cold demeanor and runs the family’s massive business, David is a playboy that's always flouncing around with a new girl. Sabrina, played by Audrey Hepburn in ’54 and Julia Ormond in ’95, grows up and travels to France in both versions. But in the former, she goes there to train as a cook, whereas in the latter, she goes there for an internship at Vogue—a reflection of changing times and career paths. Either way, she comes back not only as a changed woman, but an elegant and glamorous one at that.

Although he doesn’t recognize her at first, David quickly falls for Sabrina, disrupting Linus’ plan to have him strategically marry the daughter of an important business partner. In order to draw Sabrina away from David and obtain the deal, Linus attempts to seduce Sabrina himself, with the intention of dropping her as soon as the contracts are signed. His change of heart, however, overcomes these initial intentions and the two fall in love.

Much discussion of the two films centers around comparing them. Although most film buffs prefer the original in '54, and both films have impressive merits, I prefer the remake. The original is, of course, a classic. It features some of Hepburn’s most iconic outfits, including the first of her iconic Givenchy dresses, as well as Bogart's greatest acting elements—tragic, stoic, and powerful.

However, the cast of the remake is equally powerful. The less conservative ’90s allowed for a more romantic film to be produced, unleashing new layers of emotion. Paired with John Williams’ most underrated score, the film is a force to be reckoned with. The tone differences are ultimately insignificant—in this area, both movies excel. More intriguing are the discrepancies between the two scripts. For example, the first film contains a rather intense scene in which Linus unwittingly saves Sabrina from a suicide attempt, whereas the second chooses to flesh out Linus’ reputation as “the world’s only living heart donor.”

I speculate that the portrayal of one character as more woeful than another—Sabrina in the first, Linus in the second—is more reflective of shifting gender norms than anything else. In the original, much of the focus is on the emotional toll that Sabrina’s infatuation with David takes on her; she attempts suicide before leaving for France and returns just as fanatical. In fact, it’s implied that she transforms herself for him. However, in the remake, she returns after having a significant relationship in Paris, and transformed for herself. David is merely a bit of fun now that she’s back.

In modernizing Sabrina, Sabrina transformed into a character far from the stereotype of an overly sensitive woman. The opposite can be said for Linus, as his remade version shows a more sensitive man. Admittedly, as Bogart portrays him in the original, he wallows in his loneliness following exposure to Sabrina’s charms.

But in the remake, it's more clear the price he has had to pay for years of stoicism and detachment. Ford portrays a man who starts to believe rumors that he's robotic and less than human, only to finally have them disproved as he begins to experience love. The emotional journey that Linus goes on stretches far beyond the expectations for a man of the 1950s—this vulnerability is certainly an element permitted by our more modern era.

Towards the beginning of Sabrina and Linus' story arc in '95, she explains to him that the story of her namesake poem, Sabrina Fair, is about "a water–sprite that saves a virgin from a fate worse than death".

"Sabrina's the virgin?" Linus assumes.

"Sabrina's the savior." In this twelve–second vignette, the subtle change from the '50s to the '90s is at its most fully realized, and is accompanied by a powerful nuance.

Ultimately it's clear that one of the play's most prevalent themes is that "love conquers all." In either iteration, the films' ability to present both the power and miraculousness of love is artistically impressive and near unparalleled. Both films embody the timelessness of romance, which in turn keeps the story itself alive.