Maybe you’ve watched one of BuzzFeed’s videos like “Women Try Manspreading For a Week” or listened to a couple of episodes of the podcast Call Her Daddy. It could be one of the episodes where the hosts attempt to convince you that men who prey on women for casual sex are just “masters of the dating game” or another one where they discuss a woman's "ranking" based on her physical features and attractiveness. Even if you haven’t consumed either of those media, you’ve probably seen some catchy “feminist” slogans on T–shirts and merch like “Feminist AF” or “Yes to Masks, No to Bras,” or some company’s pink branding which supposedly tells you that they care about women’s issues.

These articulations of feminism can be identified as “choice feminism,” or liberal feminism—the mainstream type of feminism in the United States—and it often gives the movement and ideology a bad name. How does eliminating manspreading liberate women from misogyny?

Choice feminism can be understood as the idea that any action or decision that a woman takes inherently becomes a feminist act. Essentially, the decision becomes a feminist one because a woman chose it for herself.

What could this look like? It could really be anything.

Wearing makeup is a feminist act. Not wearing it is also a feminist act. Shaving or not shaving. Watching one TV show over another. Choosing a certain job over another. Listening to one artist over another. Picking a STEM career. Choosing to dress modestly or not. The list goes on.

At first glance, there does not seem to be an apparent negative consequence of choice feminism. A woman’s power is within her choices, and those choices can line up with a feminist ideology. For example, a woman’s decision not to shave may be her response to Western beauty standards that are forced onto women. Not shaving may make her feel beautiful, comfortable, and powerful, and there is nothing wrong with that. Women making choices that make them feel good is not the issue. The issue lies in calling these decisions feminist ones.

Choice feminism accompanies an amalgamation of problems—the first being that this iteration of feminism operates on faulty assumptions about said choices. Liberal feminism neglects the different realities that exist for different women—especially the difference between white women and women of color, transgender women and cis women, etc. Not all women have the same circumstance and access to choices, not all choices made by women are treated equally, and not all choices are inherently feminist.

We can look at various examples where this rings true. Even in the shaving example, we can criticize the act of shaving or not shaving as being feminist. Women who shave for themselves are still placed under the male gaze, which implicates and influences their decisions. Why would you shave for yourself if men don’t?

Another case of the fallibility of choice feminism is that not all women have the same access to choice. This is evident when we take a look at a recent feminist movement: bimbofication. Bimbofication occurs when women present their personality, clothing, makeup, etc. to align with a traditionally understood “bimbo,” but with the intention to undermine the idea that women who are very beautiful are unintelligent. While there are criticisms of the bimbo movement, the point of contention lies in how the majority of new–age bimbos blowing up across media are white women.

If women of color, and in particular Black women, were to participate in this trend, there would be violent repercussions. Black women and Asian women are already in a state of hyper–sexualization. Because these women suffer from disproportionate rates of sexual violence, participating in Bimbofication would most definitely be implicated by these realities. Therefore, it would not be an accessible or safe choice for Black women or Asian women because they have to consider how their expressions of femininity would affect their safety.

One of the most insidious and dangerous narratives that choice feminism feeds women is that their choices are always their own; it argues women exist in a vacuum without the influence of society’s pervasive misogyny. A notably recent example of this disposition can be observed on TikTok and Twitter. Grown women make posts targeting girls—17 and younger—that proclaim the allure of seeking out sugar daddies. They upload lessons on making OnlyFans accounts and selling feet pictures when they turn 18. A large–scale grooming tactic is taking place on social media and being spun as a “feminist choice.”

A women’s decision to be a sex worker can be a feminist one, but this is not. Telling young girls that they can get rich quickly by selling their bodies, and telling them these choices make them feminist, is both extremely dangerous and wrong. Choice feminism tricks young girls into believing that their exploitation is justified because they made that decision, even though it is steeped in society’s desire to manipulate and exploit young women.

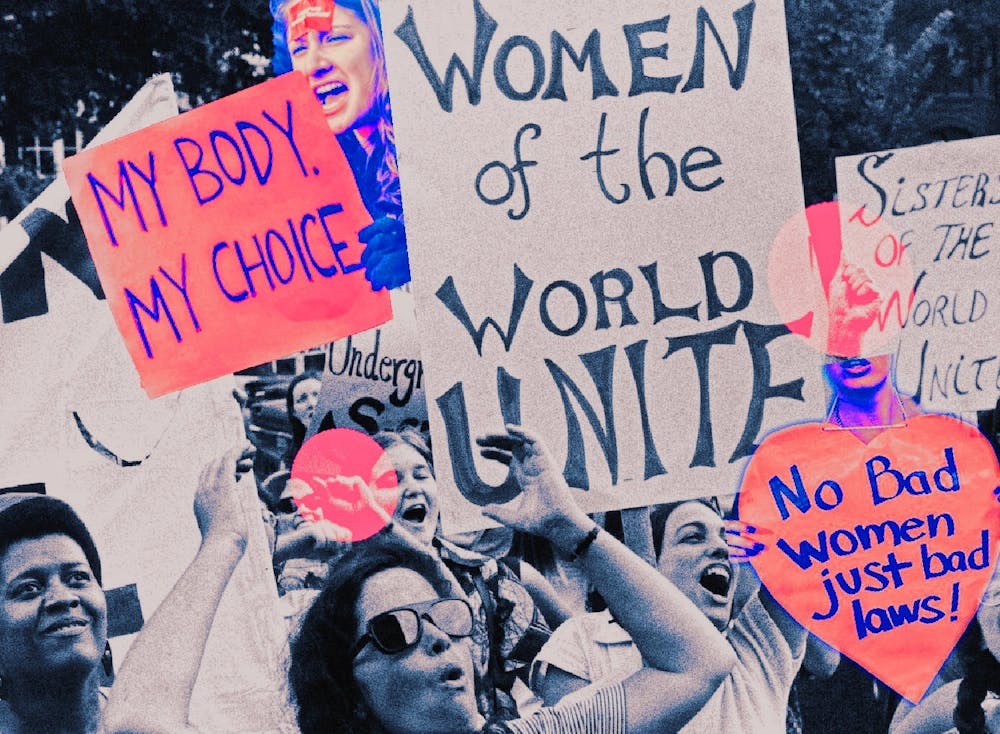

In addition to the previous problems, choice feminism also implies that the solution to gender oppression and misogyny lies in our personal choices—that we alone can make the changes we need to be lifted from the weight of oppression. This is not the case. Misogyny and the patriarchy are systemic issues that require movement organizing in order to make real changes and differences in the ways that women experience their lives everywhere. Getting caught up in the weeds of choices—is this album more or less “feminist” than another—will not be the decision that frees us. We should make these individual choices for ourselves—choices that make us happy and empowered—but we need to unite as women in order to form a movement that can liberate us from misogyny and the patriarchy.