Roberto Lugo’s Philadelphia is a “home of Cornbread tagging in the streets,” and of “football with no pads,” where you can get “baseball bats to the face for steppin’ in the wrong neighborhood.” This Philadelphia is not so familiar to the Penn community—our home is more appropriately described by tree–lined brick pathways, long walks to DRL, and consulting club rejections. Lugo’s Philadelphia and Penn’s Philadelphia may exist in the same geographical vicinity, but they often feel worlds apart.

God Complex: Different Philadelphia is Lugo’s juxtaposition of these spheres. His own experience as a North Philadelphian, Puerto Rican–American interested in history and the global arts pushes the boundaries of the exhibition’s institutional venue, Penn’s very own Arthur Ross Gallery.

By trade, Lugo is a renaissance man: an artist, activist, spoken word poet, educator, and ceramicist. In 2019, the Office of the Curator, with a grant from the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation, invited Lugo to curate an exhibition that drew from the University art collection—which holds over 8,000 pieces. Lugo decided to create an exhibition that placed his own work in dialogue with Penn’s. “I didn’t see a lot of representation in terms of the people that were painted or the concepts or ideas,” he says in a virtual gallery talk, “also, makers that are people of color or women or anybody other than a white man.”

Upon entering the gallery, the visitor observes Lugo’s intended dialogue right away. The gallery naturally progresses from portraits of early American politicians, hanging on walls the same color teal as Independence Hall, to Lugo’s own work, spread throughout a graffiti–covered space with a strong sense of racial justice.

“Bridges” occupies a poetic space between these two dichotomous sections. The installation features a large pot depicting Benjamin Franklin on one side and Lugo’s father on the other. Visual elements, including the chain–like design behind the faces, emulate the architectural qualities of the Ben Franklin Bridge. The pot tells the story of Lugo’s father, who rode his bike over the bridge to New Jersey each day for work. Through this work, Lugo expresses immense gratitude for his father and other people in his life who worked tirelessly to help him get to where he is today. He pays homage to them in kind with his own creativity. “Bridges” was generously donated to Penn and will become a permanent fixture in the University collection.

Once visitors have crossed the metaphorical bridge, they find themselves immersed in Lugo’s hand–painted pots, vases, and other work. The objects are decorated with ancient Greek motifs and feature the faces of influential Black individuals. Lugo's style utilizes techniques from around the world like the Japanese Imari style or African and South American textile patterns. From the exhibition, it is clear that Lugo is capable of skillfully manipulating porcelain, “illuminating its aristocratic surface with imagery of poverty, inequality, and social and racial injustice,” according to Arthur Ross Gallery Executive Director Lynn Marsden–Atlass.

Lugo’s “Street Pots” exemplify his trademark style. Each portrays two iconic Black figures like President Barack Obama and rapper Slick Rick or abolitionist Harriet Tubman and musician Jimi Hendrix. By creating unlikely pairs of influential people, Lugo makes a point about how no individual’s contribution is more valuable or worthy of celebration than another's—honoring them all for uplifting the Black community in their own way. His teapots achieve a similar effect, memorializing figures like Caroline LeCount, a teacher and Civil Rights Activist, and Crystal Bird Fauset, the first Black woman elected to state legislature in the United States. “These are my George Washingtons and Ben Franklins and my ancestry that created all these things for me to be able to go to college for something like pottery,” Lugo says.

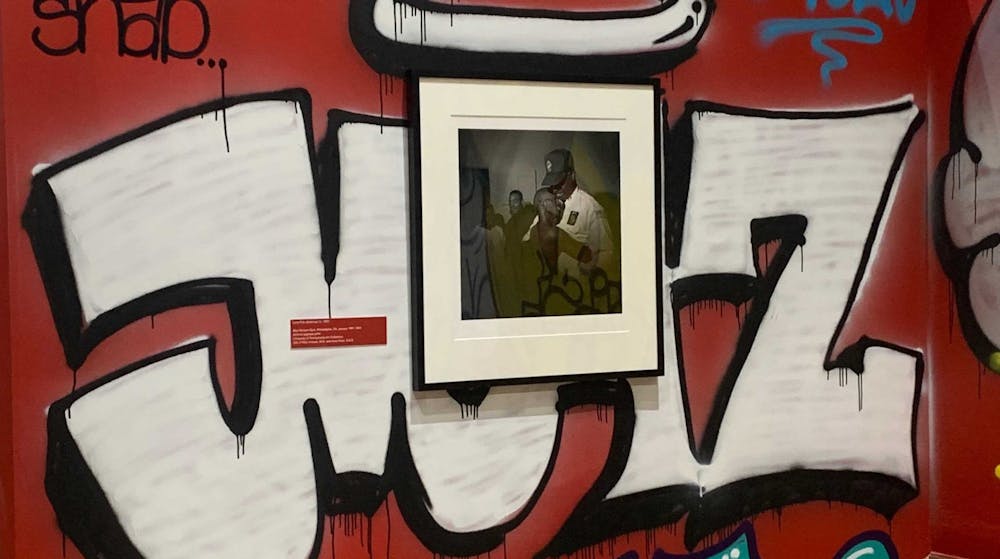

The graffiti that covers the walls of the gallery is just as engaging as the objects the space houses. Growing up in Kensington, Lugo’s primary exposure to art was through the Mural Arts Program, an initiative which is responsible for inspirational murals around the city. This in addition to graffiti, a skill passed on to him as a young man by formative community role models. Working with Chop, a fellow graffiti artist, Lugo spontaneously graffitied the gallery walls, trying to achieve a layering effect common on city walls that get covered, sprayed over, and covered again. To Lugo, graffiti is an “art movement of overcoming oppression” that allows those who don’t have an art class to express themselves, thus leaving a meaningful mark on the community.

As someone who has won a variety of awards and has displayed work in museums like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and The Brooklyn Museum, this exhibition at Penn may seem less impressive. Given both Lugo’s background and the school’s history, God Complex is actually incredibly personal and impactful. “My Philadelphia exists in the same Philadelphia that Penn exists in,” Lugo says. “I feel like it’s my responsibility to work with institutions like this in order to move the goal post in the right direction, which is us acknowledging these histories, doing away with celebrating just one narrative, and to be able to explore and support artists and thinkers with a lot of different experiences.”

God Complex: A Different Philadelphia is a step towards that goal post, and is a free, convenient, and engaging way for Penn students to start breaking out of their bubble. It is undeniable that the exhibition will influence the art community on campus, in Philadelphia, and writ large far beyond its close.