Formula 1 will have its inaugural Qatar Grand Prix this coming Sunday, which means that the Twittersphere is abuzz with hot takes galore. Fans mock F1’s various attempts at social justice initiatives: “we race as one except if there’s money, in which case f**k you” or “#WeRaceForMoney,” and so on. Whenever F1 takes place in a nation such as Qatar (other examples include China, the UAE, Russia, etc.), there is a common rallying cry: what about human rights?

If someone wants to find a collated list of Qatar’s human rights violations, the United States Department of State provides a handy summary, and, seeing as the issue is not limited to Qatar, they also do this with almost every single nation not named the United States of America. Withholding sporting events from—or even not advertising in—certain countries as punishment for committing human rights violations is an almost universally agreed–upon plan of action, even among the “keep politics out of sports” crowd.

In the simplest terms, most people agree that human rights are good and violations of human rights are bad. That naturally leads to the conclusion that sporting institutions (such as the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile, which controls Formula 1) should not host events in ‘bad’ countries (such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, etc.) as a form of activism or protest. Sen. Ted Cruz and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez even agree on it!

That’s one hint that the whole issue might deserve a little bit more interrogation.

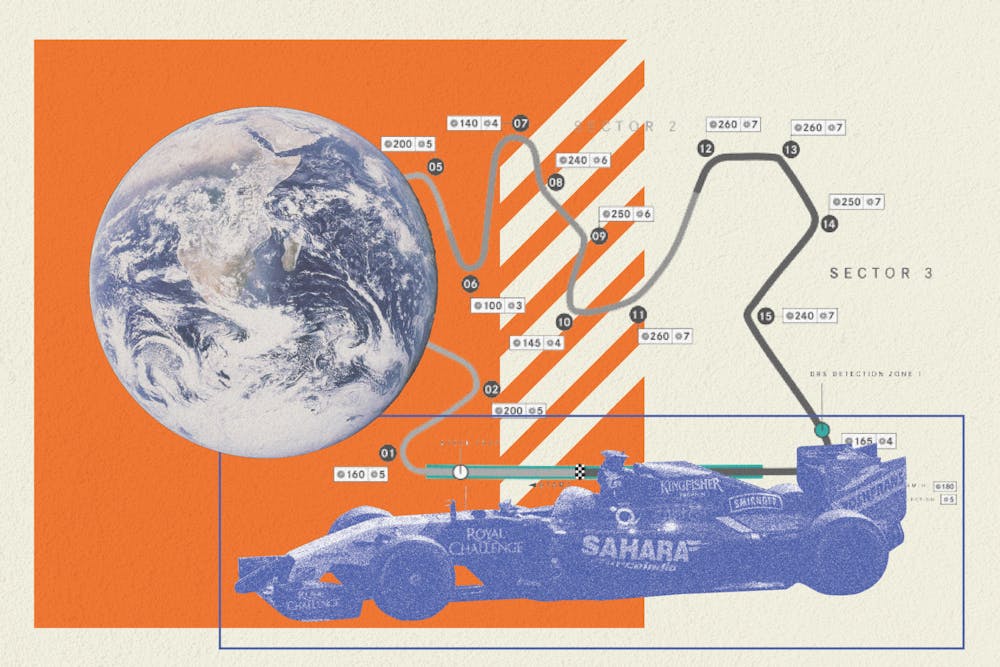

The Qatar Grand Prix’s existence is a product of an inflated calendar during a raging pandemic. Qatar wasn’t even on the provisional 23–race schedule for 2021, which would’ve marked the most races in a single season in F1 history. But in the midst of the COVID–19 pandemic, the schedule was constantly changing, with races in certain countries moved up by a few weeks while other races got postponed or canceled. Grands Prix fell like flies, until eventually, in order to at least put out a 22–race schedule (still the most races in F1 history), the Qatar Grand Prix was announced.

Schedule bloating, despite the detrimental effects on the environment and grueling travel and working conditions for teams and mechanics, follows the same motivations as hosting races in countries with Western reputations as human rights offenders, or going ahead with the 2020 Australian Grand Prix despite the spread of COVID–19—in the wise words of Sir Lewis Hamilton, who is heralded as one of the greatest F1 drivers of all time, “Cash is king.”

The notion that races should be a reward for countries’ moral sanctity is fundamentally broken, if just for the fact that it upholds the FIA (and any other governing corporations for sports, which are ultimately frivolous and built for profit) as an arbiter of justice. To go further, the very question of “human rights” and sports raises similar questions: who defines what a human right is, and who gets to punish violations of such human rights?

You have to take care in avoiding whataboutism when suggesting that human rights violations take place everywhere, not just in the laundry list of commonly agreed–upon, human–rights–violating countries such as Qatar. When fans discuss human rights violations, their lists are almost always limited to non–white, non–Western nations. While there may be an acknowledgment that practices such as the forced sterilizations of indigenous women still take place in Canada or the hoarding of COVID–19 vaccinations by wealthy countries are human rights violations, Western countries are often not labeled as human rights violators.

But a baseline for how many human rights violations are too many human rights violations just doesn’t exist. Any interrogation of holding sporting events in ‘bad’ countries requires diving into a deeply interlocked system of injustice perpetrated by every single nation. Doing this would drastically broaden the definition of what a ‘bad’ country is and put into question our consumption of sports and entertainment in general.

This is not a suggestion that fans shouldn’t care about human rights abuses in other nations, or that the impossibility of having a consistent ethic under capitalism means that fans shouldn’t try. It’s that fans and people at large should discuss these issues with nuance and consider how the ways through which we receive information influence what issues we care about and what issues we don’t. These things that require slightly more than a pithy play on words that would hit the right margin between joking and seriousness to get likes on Twitter.

In returning to the Department of State’s list of human rights violations in Qatar, you’d find that many of them could neatly be used to describe the United States: “restrictions on peaceful assembly and freedom of association, including prohibitions on political parties and labor unions” (state–sponsored actors tear–gassing Black Lives Matters protests; Amazon corporate union busting) or “restrictions on migrant workers’ freedom of movement” (deportations and treatment of undocumented immigrants) or “limits on the ability of citizens to choose their government in free and fair elections” (suppression of voters rights in the South) or “lack of investigation of and accountability for violence against women” (police violence against women; poor treatment of sexual assault cases; Texas abortion legislation) or “reports of forced labor” (prison labor as modern–day slavery).

It’s far easier to talk about other nations committing human rights abuses in large part because the language to do so is well–established. There’s a reason why people can believe that politics and sports don’t mix but still advocate for withholding sports from certain countries—because human rights are often treated as a separate entity.

If it takes place in Qatar, it’s a human rights violation. If it takes place in America, it’s politics. If an issue is big enough in America to be considered a human rights issue, such as Black Lives Matter, then the separation between human rights and politics allows for a simplistic way of unilaterally denouncing nations or oppressions, compiling a list of easily check–marked moral positions without engaging with the material ways through which injustice is formed or can be fixed. The simplest example is posting a black square and still voting for Trump.

Talking about human rights abuses in places other than the West is easy because the situation is reduced until the people involved are barely people anymore, instead viewed as a sea of foreign victims amidst foreign oppressors.

All the Western fan needs to forfeit is having F1 not participate in those nations, races that would likely be replaced by ones in other more palatable locations. Pulling F1 races out of Qatar for its human rights violations would do little to nothing to aid those harmed by such oppression, but it would make watching F1 races more guiltless.

The focus on sporting events in relation to human rights turns consumption into activism. At the end of the day, sports are frivolous, profit–making endeavors. Especially during COVID–19, they probably shouldn’t take place anywhere. Instead of tweeting, all those appalled by human rights abuses should interrogate why it is so much harder to denounce such issues when they take place domestically rather than abroad.