Terry McMillan achieved national attention with her third book, Waiting to Exhale, in 1992. It was a huge success, remaining on The New York Times bestseller list for several months. When crafting up her characters—four single Black women in Arizona in the '80s—McMillan couldn’t have foreseen social media or a global pandemic, let alone manifestation TikTok. Even so, McMillan’s novel reveals how social expectations placed on Black women prevent them from taking part in the relationships that they are taught to aspire to. Andin the 30 years since the novel's release, these societal expectations and aspirational relationships have only gotten harder to reach.

For Sarah Adeyinka–Skold (GR '20), her experience as a Black woman at looking for a romantic partner as an undergraduate at Princeton, then as a doctoral student in sociology at Penn, led her to write her dissertation: “Dating in the Digital Age: Sex, Love, and Inequality.” She found that when it comes to dating in the 21st century, place matters. She spoke to Omnia, Penn’s alumni magazine, and shared her discovery that residential segregation contributes to obstacles in dating for Black women. Professional women are increasingly going to up–and–coming “urban professional centers,” new places where finding love as a Black woman can prove difficult because of rampant gentrification and negative stereotypes against Black women. Here at Penn, a competitive preprofessional environment that pushes students to academic and professional extremes can lead Black female students to feel like romance and a career are mutually exclusive.

This issue is central to McMillan’s plot. Savannah, the central character, is moving from Denver to Arizona for the opportunity to get closer to her desired career, but she often stresses the hope that there are more romantic options for her there. Savannah, like Adeyinka–Skold, finds it difficult to secure a partner, and while other characters in the novel tell her that time is running out, she maintains her belief that with patience the right one will come. This waiting rhetoric is all over social media today, especially with the uptick in healing and self–care media since the COVID–19 pandemic. This media places a premium on confidence and mindset as it relates to attaining love.

This “when you focus on yourself first, love will come,” sentiment fails to consider that for Black women, stereotypes about masculinity, sexuality, and independence (think: the "strong Black woman," or the "sassy Black woman"), add systemic obstacles to their journey towards finding love. Like Savannah’s case, one trope, as seen in shows like Scandal, Being Mary Jane, and How to Get Away with Murder, is the high–achieving, lonely Black woman. Considering that Black women are enrolled in college at a higher percentage than any other demographic and that Black women are significantly less likely to be married than white women, this trope can feel like a prophecy or a cautionary tale for Black women at Penn. While a simple mindset change and some confidence can’t erase centuries of racism and sexism, Waiting to Exhale affirms Black women’s power to lead fulfilling, loving lives by decentering romance.

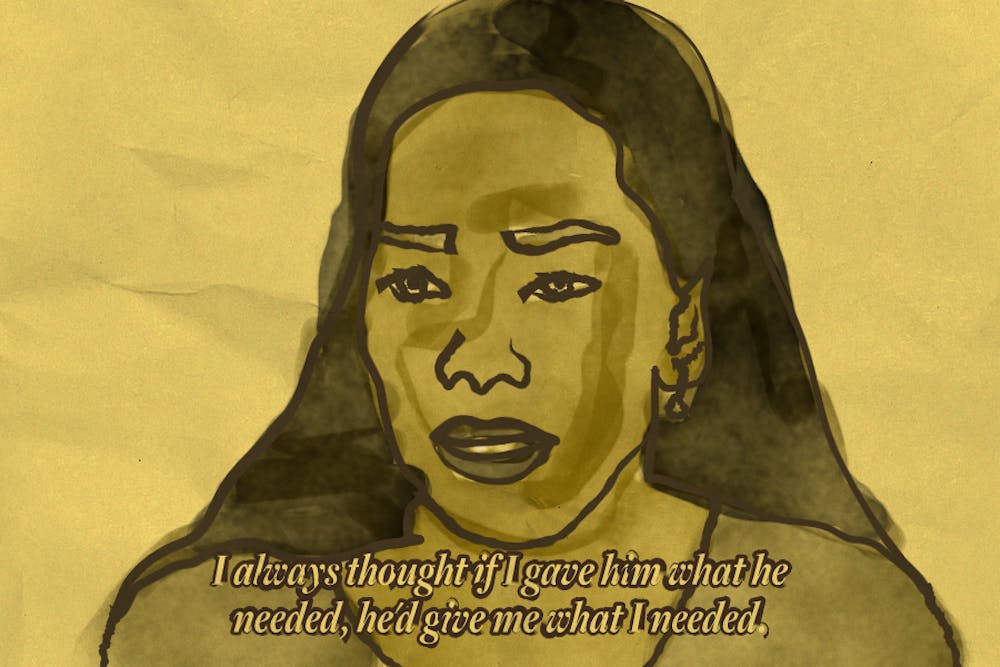

On Goodreads, the description for Waiting to Exhale reads, “The story of friendship between four African American women who lean on each other while 'waiting to exhale:' waiting for that man who will take their breath away.” But these characters aren’t waiting for a man to leave them breathless from excitement or butterflies—they're waiting for a man so that they can finally breathe. Savannah thinks, “I worry about if and when I’ll ever find the right man, if I’ll ever be able to exhale,” (17). Robin has financial problems a husband could solve, Bernadine is getting divorced from a man who acted as the breadwinner for their family. Savannah is just plain old lonely, while Gloria is raising a teenage Black boy alone in a white town. In many ways, they are waiting for someone to save them from their lives. What they really wanted, it turns out, was not a man, but the ability to exhale.

Exhaling, as I interpret it, is feeling safe enough to stop worrying. It’s feeling for a second like life might work out okay. Waiting to Exhale unveils the challenges of dating as a Black woman, the power of decentering romantic love in your life, and the importance of sisterhood. It's not that you shouldn’t want a partner or to fall in love, but that in holding your breath for “the one,” you miss breathing in love in all its forms along the way.