Most of women’s history is hidden in plain sight. From an unmarked painting in the background of your study session to the sidewalk you walk on to class, the souls of women linger throughout Penn. The art across campus tells a chronicle of women’s invention that has become invisible over the years. Explore these ten pieces from Woodland Walk to the Penn’s Women's Center – all either created by female artists and architects or honoring female figures in Philadelphia’s history.

125 Years, Jenny Holzer (Location: Hill Square, University of Pennsylvania, 34th and Walnut Street)

Crossing 34th and Walnut, notice a stone bench inscribed with a 1921 editorial from The Pennsylvanian: “We are absolutely opposed to co–education at the University of Pennsylvania.” Penn’s history of women on campus is illegible, literally—with historical quotes smothered under damp leaves and eroding underneath winter boots—but it's still the foundation we walk upon. On what looks like a live news ticker of rolling headlines, architect Jenny Holzer’s 125 Years is a physical timeline of women at Penn. When you are grabbing your next lunch at Hill, pause to read from the long stone path of voices along Woodland Walk from some of the first female students on campus.

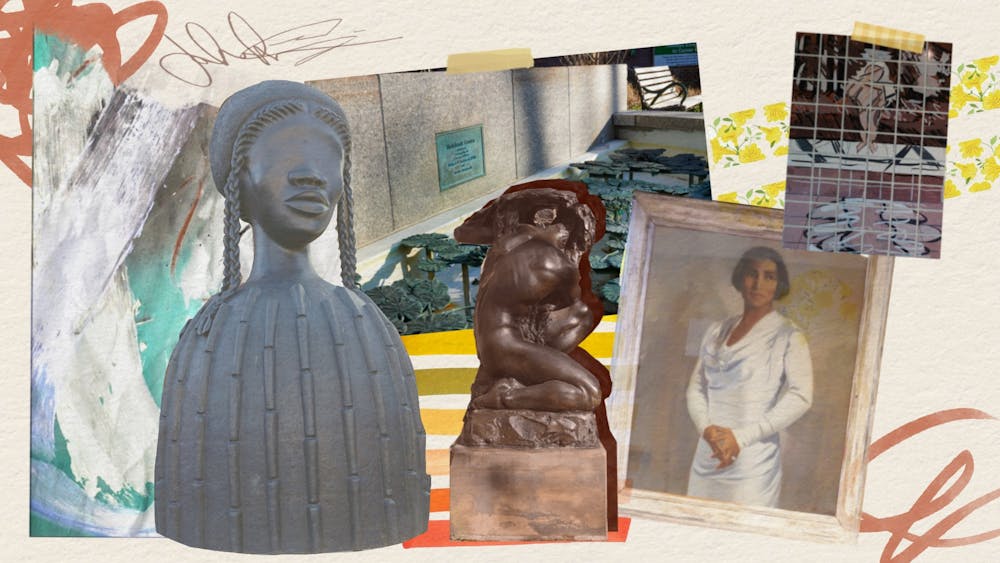

Brick House, Simone Leigh (Location: 34th and Walnut Street)

When Simone Leigh constructed Brick House, a towering bronze bust of an African woman, she intended it to be a timeless mirror for Black, female students. The sculpture, newly erected in 2020, reclaims the sexualized slur against women into a complexion of dignity and self–respect. Brick House is one piece in a series titled Anatomy of Architecture. This figure achieves that interchangeable effect between elements of humanity and architecture with four symmetrical braids held together by seashells that trickle down into a bead–like pattern. On your way to College Green, this work of art is a reminder of the spirit of Black femininity in West Philadelphia.

Lily Composition III, Anne Froehling (Location: Steinhart Plaza, Woodland Walk)

Passing Joe’s Cafe in the center of campus, Anne Froehling’s sculpted water lilies are suspended in a crescent pond. On a warm day, her lilies are glossy with sunlight, giving the illusion of real leaves and lotus blossoms. At Penn, Anne Froehling was an active architect and painter, whose art remains in the university's archives. Erected in 1993, this small oasis is one example of her underrated body of work that remains sadly unremarked to those who sit beside it everyday.

Pan with Sundial, Beatrice Fenton (Location: Van Pelt Library Ground Floor, Rosengarten Court)

One of the hidden spots in College Green is the courtyard outside of Van Pelt’s ground floor where Beatrice Fenton’s sculpture sits. On the square of cobblestone, Pan with Sundial depicts a crouching man balancing a sundial on his shoulder while whistling into a pipe. Fenton, who passed away in 1983, was a local artist who studied at PAFA and went on to teach at the Moore Institute of Art, just down the street from her personal studio located at 15th and Chestnut. Her most famous work, Seaweed Fountain, is on display in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, depicting a child playing atop a sea turtle’s shell outside of the Horticultural Center.

Fields of Transformation, Claudy Jongstra (Location: Moelis Family Grand Reading Room, Van Pelt Library First Floor)

If you make a sharp right at the entrance into Van Pelt's Moelis Family Grand Reading Room, you'll find a mural that makes up a pastel landscape. The piece, called Fields of Transformation, moves like ancient swirls of cloud slowly migrating into earthy stitches of wool. But as surreal and extraterrestrial as it appears, the piece is actually a science experiment. The artist, Claudy Jongstra, is known for using organic materials, going as far as growing her own plants for dyes and supplying her own fibers. She does so because natural materials are vulnerable to natural reactions; being wool, the mural itself can retain moisture, respond to sunlight, and even be a source of food to some insects. Since 2019, the intensity of the colors and texture has not faded, but become an entirely different piece just by taking away the barrier between art and nature.

In The Garden, Jennifer Bartlett (Location: Seng Tee Lee Lounge, Van Pelt Library First Floor)

When we think of mosaics, we think of shattered, unmatchable puzzle pieces—but Jennifer Bartlett’s In The Garden simply uses steel squares. On a trip to France, one backyard scene inspired what Bartlett would replicate for almost half a decade. Her series has been on display from the Philadelphia Museum of Art to The Met. This installation now spans and curves around the entire first floor of Van Pelt. On the wall of the Seng Tee Lee Lounge, through dripping paint and the narrow slits between boxes, you can make out a small pool surrounded by trees in fresh blues and greens. On another wall, the same shape is vaguely repeated, this time composed of pale, grayish pinks, and with new details specified, like a statue of a boy. Next time you need a break from studying, go and put together Barlett’s moving puzzle for yourself!

The Sea, Francine Tint (Location: David B. Weigle Information Commons, Van Pelt Library First Floor)

Just a little past the Seng Tee Lee Lounge, Francine Tint’s The Sea hangs beside a set of elevators. An abstract painting, the piece crashes with wide strokes swishing like ribbons of minty seafoam green and splatters of white. The ocean is a consistent motif in Tint’s work, which is often blurry and inexact in texture, like looking down on the water’s surface itself. Francine Tint’s style of lush colors combined in psychedelic patterns make her paintings feel like they test dimensions— and her deep dive is right on the first floor.

Tri–Colored Bird, Paper Jungle I, Paper Jungle II, Paula Barragán (Location: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Van Pelt Library Third Floor)

A few flights of stairs above, a similar trip through nature is on the wall: massive dragonflies, a looming crocodile, and a distant cheetah, all shrouded in layers of forest. In between two of these paintings is a much more solitary piece: a solo bird seemingly split into three parts: a feathered frame of yellow, a body of red, and an underbelly of white. Paula Barragán’s rotating display recalls Rousseau's wonderland—like jungle paintings from two centuries before. Inspired by her home in Ecuador, her paintings are all statements against oil exploitation and other threats against the country's parks and conservatories.

Portrait of Marian Anderson, Robert Savon Pious (Marian Anderson Study Center, Van Pelt Library Fourth Floor)

Although not painted by a female artist, the Portrait of Marian Anderson is an indispensable piece of women’s history in Philadelphia. One of the first nationally–recognized contraltos, Anderson grew up in Philadelphia, going to church in South Philly and working at Reading Terminal at 12 years old. She would go on to perform at The Lincoln Memorial Concert. Her presence made her a local Civil Rights hero, and her name appears throughout Philadelphia, from Van Pelt all the way to her house, which is now a museum. This portrait of her, in the prime of her career, wearing a white gown and a subtle smile, captures the poised humbleness she carried in her music that changed the horizon for future Black artists.

Flowers in the Sunshine, Françoise Gilot (Location: Penn Women's Center, 3643 Locust Walk)

Penn Women’s Center is one of the most important sanctuaries for women on campus—whether you need a safe space to consult someone or simply share a cup of tea over a game of Jenga. Surrounding you is art entirely completed by women—one of my favorites being Flowers in the Sunshine. Resembling a more experimental version of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, Françoise Gilot depicts a warm vase of a squiggly, exotic bouquet. As the painting’s caption explains, Gilot’s fame derived a lot from her relationship with Pablo Picasso—but what she produced as an artist was entirely individualistic and original from his style. She wanted her work to take place in two acts: the first being her creation, the second her audience’s interpretation. Gilot described her paintings as intentionally filled with “clues” for a “detective narrative”—making her works endlessly renewed every time they're seen.