Museums and art galleries are known as places that answer our existential questions. However, over the last two months, the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) has only posed said questions.

As I walk into the exhibit, questions covered the walls of the gallery. A black and pink screen on a wall near the entrance asks, “How would a new arts infrastructure value artworks and art makers?”, setting the exhibition’s tone. “How can art have real life consequences?” asks a half–pipe chalkboard, with a coffee cup full of chalk hooked to the surface of prompt responses. “What do you need in order to make art?” asks a piece of paper on a pink bulletin board, written in red Sharpie and held up by a pushpin—tacked to the wall almost as if its presence was an afterthought.

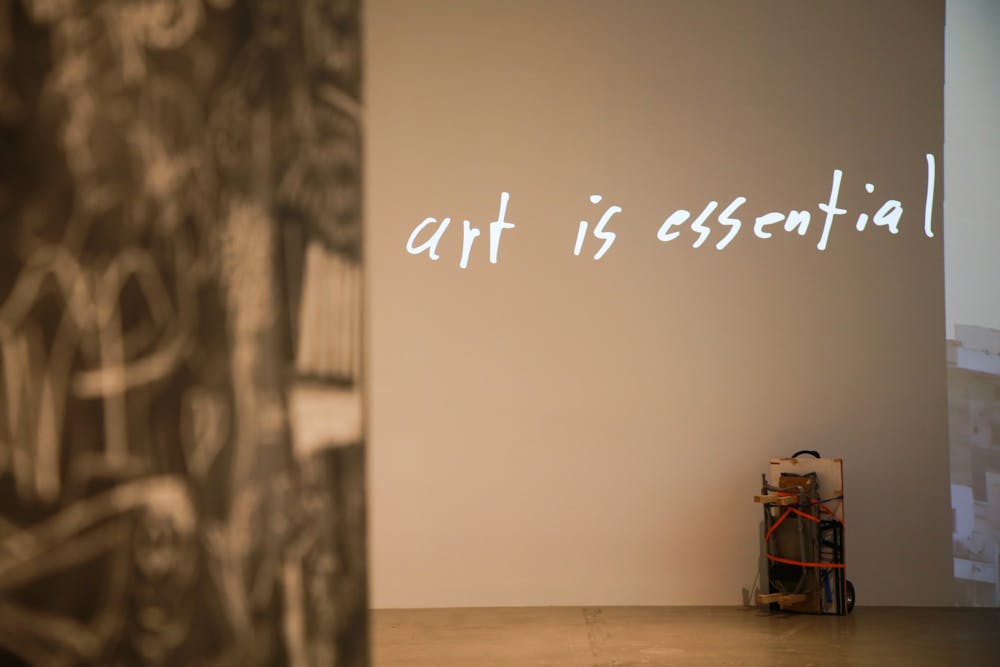

This interrogative landscape combines to create Infrastructure, an exhibition that devotes itself to challenging the titular infrastructure of the art world as a whole. It represents the mission of RAW Académie, a Senegal–based residency program devoted to, in its own words, “the research and study of artistic and curatorial practice and thought.” Headed by Linda Goode Bryant, Infrastructure is the result of RAW Académie’s ninth session, focusing on questioning art’s role within a capitalist society. It asks if art is a fundamental right, if art should ever be sold or profited upon, and whose work receives the title of “art.”

Infrastructure rarely claims to have the answers to the questions it asks, holding a uniquely humble artistic stance. It rejects the artistic norm of being (or pretending to be) the authority on its own subject material.

Instead, it expresses faith in the observer's ability to answer its questions. This faith is embedded in the collaborative, transparent architecture of the exhibition, which held public meetings with artists and scholars both involved and uninvolved with RAW Académie. Recordings of those meetings play within the exhibition for its future visitors. Infrastructure is also filled with documentation of its own creation, displaying photos of RAW Fellows’ loved ones and a bulletin board timeline of the emails and itineraries exchanged between Bryant, the Raw Material Company (which hosts RAW Académie), and the ICA ahead of Infrastructure's debut. This public documentation honors the personal context of each artist involved and enables them to help answer the exhibition’s questions. In the same way, it honors the viewer by entrusting this insider information with them, giving them the same resources it provides to its RAW Fellows.

One open–response prompt on a slim wall between larger blackboards is followed by a note reading, “Bad ideas are welcome,” encouraging visitors to share imperfect solutions in their pursuit of larger answers. Turning its back on the exclusionary art world, Infrastructure tells visitors that their opinions are recognized, welcomed, and respected, just as an artist’s might be.

Alongside its tough questions about art, the interactive environment of Infrastructure encourages less intellectual evidence of visitors’ presence. A three–year–old’s scribblings are labeled and attached to one bulletin board alongside a call for a communist art economy. A patron draws the logo of the band Rush next to a question about “art in the context of erasure.” One ICA security guard leaves simple origami hearts in various corners of the gallery room “to leave her mark on it,” she says. Every mark a visitor makes, large or small, remains displayed within the exhibition for its full duration. These little symbols don't offer answers to the exhibit’s big questions, but instead creates something just as important to its investigation: a platform where they can exist. Infrastructure wants people to be “human” within its space.

Similarly, Infrastructure seems aware and respectful of how humans consume and remember art—foggily, and as fragments. Despite its volume of content, it does not ask to be memorized. Instead, it throws all of its ideas at the wall—literally—and trusts that something useful will stick to each person who moves through the gallery.

The exhibition meets the observer halfway—within their own relationship to art. Classical art exhibitions often demand us to step up to their level and regard the art through their eyes. They authoritatively offer their answers to questions about the world, as if we have no choice but to accept them. It would be unfair to say, though, that Infrastructure steps down to the level of the viewer. Rather, it tosses out the idea of these “levels” entirely and poses its questions with the knowledge that no one individual can answer them.

We can only hope to resolve these questions as a society, Infrastructure says, by giving every voice the tools to help answer them.