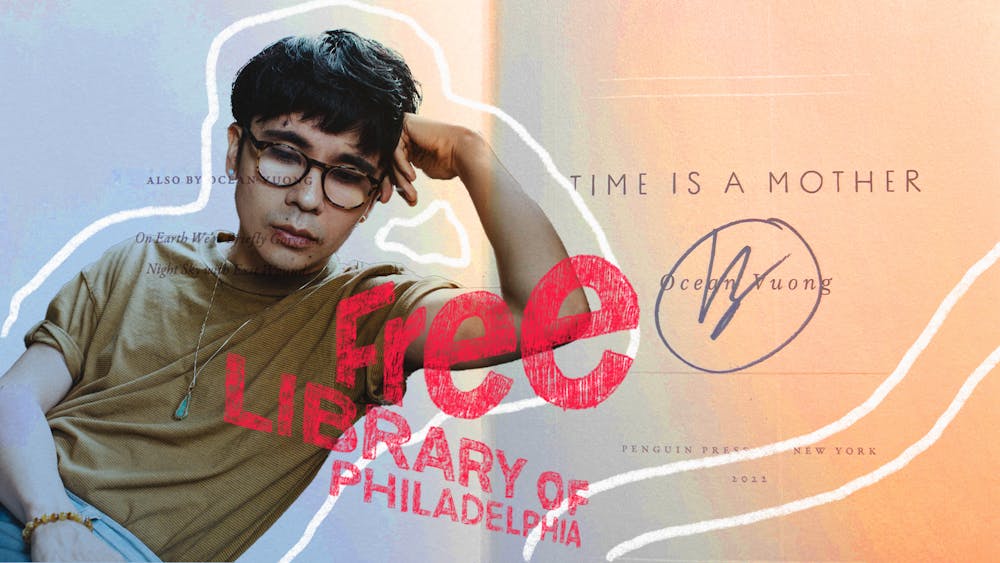

“To me, grief is the last translation of love,” Ocean Vuong says, referring to his new poetry collection, Time Is a Mother. “My life now is: Today when my mother is not here, and then whatever big yesterday where she was. It’s just two days.” In his new book, Vuong articulates his unbroken experience of grief as a queer, Vietnamese American artist. To promote its publication, Vuong read and spoke with Philadelphia Poet Laureate Airea D. Matthews at Parkway Central Library about topics ranging from wasting time watching straight boys play video games to the capitalistic limits on professional writing.

Wearing black jeans and a pop–art T–shirt of James Baldwin (and giving a quick “shoutout to Giovanni’s Room,” before reading), Vuong says, “Thank you for being a home to one of the most robust Vietnamese American communities … Thank you for holding space for us.” Then, his humble, charmingly clumsy voice takes on a melodic tone. Matthews describes it as “a jazz artist,” where the time and rhythm of his articulation feel detached from gravity. For this homespun style of delivery, Vuong looks to his ancestors.

“When I was hearing their stories, I was at the seat of masters. Because coming from refugees, you realize that when they leave everything behind, they are making a creative act. Nobody survives by accident.” Vuong explains how his family subconsciously “trained” him to be a writer. “They would edit it down: My grandmother knew when to pause, what to embellish, exposition, she had us hooked. The permission is instilled in my upbringing. Every time my grandmother told a story, she told it differently.”

Vuong is intentional when it comes to both honoring his family and assigning his writing a genre. For example, his last work, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, is technically a fictional novel, but mostly inspired by real–life events. However, he says he could never write a memoir because he believes memory interacts almost chemically with the incident of creativity. He says that the imagination is an essential filter when converting experience into art.

“I do not own my mother or her stories; I own my understanding and reception of them. It's important for me to know that my grandmother is gone, my mother is gone, and they left with their complete lives intact, and I never touched them,” he says.

Vuong discusses the industry’s expectations of varied subject matter from the same artist versus his personal process. Vuong says that “obsession” is intrinsic to how he processes his emotions when translating them into a poem. This is clear not only in his choice to return to his mother’s death, but also with his own grammar and format. To him, the manipulation of language is a revolution against the classicist, colonial institution of standard English.

When you read Vuong’s poetry, punctuation is rare. Instead, he spaces words as if the paper lacks corners, chipping a poem into fragments. He asks the audience, “Why should the arbitrary front and back cover be an ultimate continuum of our questions? There is a capitalistic anxiety that the book should finish the thought.”

He explains that the “cohesion” of syntax and linear time are impossible mediums for the surrealism of trauma. Stories of immigration and the endurance of being the child of refugees crafted Vuong’s childhood. He believes that the dimensions of Western storytelling inherently do not provide the space to define this cultural experience—especially when it is chaos brought on by those who exist in order. Vuong uses the analogy of an artifact, questioning, “Why is the impulse of the museum to restore the artifact? When we find the broken pot, the inclination is that we restore it to its origin.” He continues, “The West has an obsession of the origin as the truth, but when you restore it, you erase the violence that made it fragmented in the first place.” To him, the need for a beginning and end is an act that covers up the truth.

According to Vuong, this conquest of language still exists in the same “room” as love. He says, “When your mother dies, you become like a child again; I lost my North Star.” But, as Matthews responds, “When we read the text, we recognize the speaker to still be grieving.”