Editor's Note: This article contains spoilers for Season 3 of 'Ted Lasso'

When I came back home for the summer, the first thing I looked forward to was curling up with my family on our decades–old red couch for the final season of Ted Lasso, an Apple TV Original that follows an upbeat American football coach stuck managing AFC Richmond, an English soccer team. Over the last few years, the titular Ted Lasso (Jason Sudeikis) has become a part of my family. My mom leaves sticky notes with the quotes from the show around the house, and even my dad has adopted some of Ted's quips. While the only American soccer player I can name is Meg Rapinoe, my sister and I would have in–depth discussions over the starting positions of Coach Lasso’s players.

My family isn’t the only one rooting for Ted Lasso. Their first and second season racked up 40 total Emmy nominations and wins. The show has even been credited with sparking a new American interest in soccer. My high school U.S. government teacher used Ted Lasso to explain checks and balances.

Beyond the hilarious hijinks of AFC Richmond, part of Ted Lasso’s appeal is its willingness to address current issues on screen, displaying frank conversations about mental health and flipping the narrative on toxic masculinity in sports. However, in the final season, as the show attempted to tackle issues of queer identity, the writers seem to trip on their shoelaces.

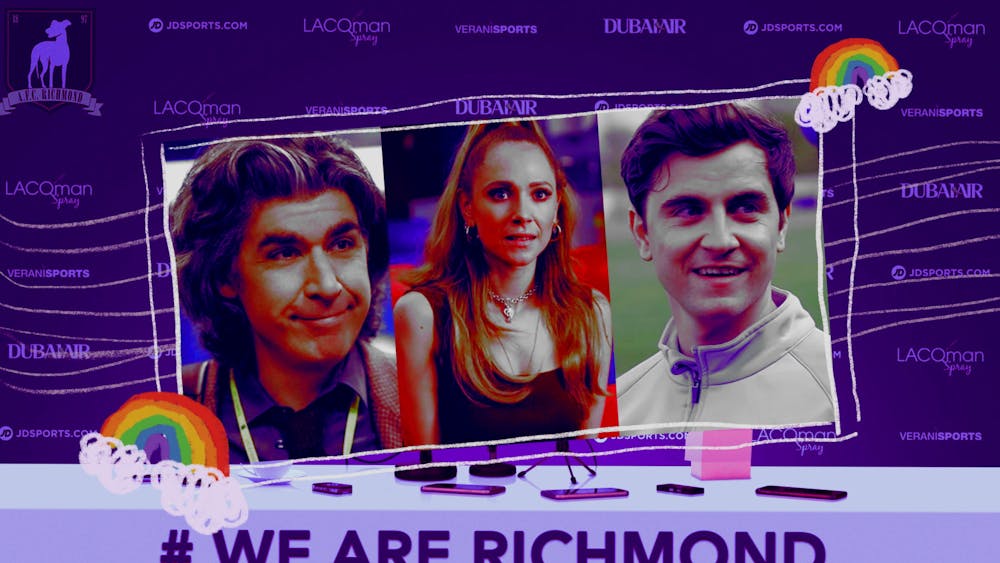

Two independent queer storylines emerge in season three. One is the more traditional—one may even say overused—trope of the coming–out story. In season two, one of the players on Ted’s team, Colin Hughes (Billy Harris), makes a reference to Grindr, and in season three, the once–minor character gets a chance to develop his own storyline as he is seen kissing his partner early on in the season, but struggles to come out to his team.

Only a handful of professional male athletes have come out. Male athletics is often considered “The Last Closet” for its lack of queer representation due to cultural stigma. But in Hollywood, the coming–out story is everywhere. It’s the plot of Love Simon, Happiest Season, and plenty of other Hollywood films that have received criticism for catering to straight audiences. Sure, it’s an overused plot line, but the Lasso way has aspects broaching the topic that are refreshing compared to its predecessors.

Colin recognizes early on that his team would likely accept him, and once he finally comes out, not only do they accept him, but they actively support him. Colin even gets that on–field kiss with his partner that he had long dreamed of. There’s a nuanced conversation in the locker room about what it means to be a good ally, and Colin even clarifies to his best friend that "top" and "bottom" are not, in fact, bunk beds.

Yet at the same time, Ted Lasso falls into the quintessential trap of a forced outing, a problem for Hollywood both on screen and off. Colin is forced to admit he was gay twice, once when journalist Trent Crimm (James Lance) follows him to a gay bar, and again when the team captain finds incriminating photos on his phone. Sure, in this case, these forced outings aren't necessarily malicious; Trent too admits he's gay, and his captain is only angry about the photos because he wishes his friend could have told him the truth. But the fact remains Colin had no agency in when he came out but rather was forced to by surrounding pressures. The issue here is not necessarily specific to Ted Lasso, but rather the larger treatment of coming–out stories in Hollywood. When Hollywood makes the fallacy of first centering queer identity on coming out, and then taking even that out of the queer character’s control, a certain empowerment is lost.

The other queer storyline follows Keeley Jones (Jude Temple), a bombshell model–turned–PR entrepreneur. After Keeley breaks up with her long–term boyfriend Roy Kent (Brett Goldstein), a coach for AFC Richmond, she begins a relationship with Jack Danvers (Jodi Balfour), an investor in her newly–formed PR firm. Jack oozes girlboss unironically, from her pantsuits to her private jet. “Epstein rich,” she calls herself.

Keeley’s relationship with Jack has none of the nuance nor build–up that the rest of the show's relationships exhibit. Instead, she enters into a serious relationship with Jack within an episode of the pair's first meeting and only a handful of conversations between them. While we're all familiar with the lesbian UHaul stereotype and the show even ventures to have conversations about love–bombing, the rushed plot line leaves the viewer with the icky feeling that this rushed storyline is simply an attempt to confirm Keeley’s bisexuality on screen (which had previously been only ambiguously referenced). If Jack had gotten the chance to become a more nuanced character beyond her role as a tool to represent queerness, maybe this speedy relationship could be forgiven. Instead, the show redeems nearly every other character on screen, even offering a humble backstory for the villainous Rupert, but leaves Jack as a two-dimensional character for the rest of her tenure on Ted Lasso (which, frankly, isn't very long). She never gets integrated into the larger plot line of the show and abruptly disappears five episodes after her first appearance.

In fact, the only notable consequence of Jack’s presence is the fact she pulls funding from Keeley’s company, leaving Keeley distraught and of course back in the arms of her ex–boyfriend Roy. By the end of the season, Keeley’s two ex–boyfriends Roy and Jamie Tartt are left fighting over her once again. While Jamie points out he was with her first, Roy points out he was with her last—Jack entirely forgotten in between.

You can’t help but feel like Keeley’s queerness is an afterthought. A minor chapter without much consequence. While her first season relationship with Jamie continues to be referenced years later into the third season, Jack isn’t mentioned once after she suddenly disappears to Argentina.

However, not every queer relationship on–screen needs to be significant—in fact, there is much to be said about casual relationships normalizing representation. The larger problem in Ted Lasso is the significant disparity between how Keeley’s relationships with men are treated compared to those with women. It’s part of a larger trend off–screen as well, where bisexual women’s relationships with men are consistently taken more seriously.

Representation is important. When our favorite stories show our stories, it's a reminder that we’re all part of the narrative. But when identities are reduced to a checkbox without fully including them in the story, that's not inclusion—it's pandering. Ted Lasso isn’t the only recent show that has taken shortcuts in attempts to include LGBTQ storylines. Shows like Never Have I Ever carry similar issues where they center queer identities on coming–out stories or distill the romantic nuance from queer relationships. It’s a larger issue in Hollywood that Ted Lasso is unable to outrun. For all the innovation it shows in reframing the conversation around masculinity, mental health, and even love (of the heteronormative strain), when it comes to queer storylines, Coach Lasso doesn’t introduce a new play.