When it comes to dating decrees, all women know that there’s only one rule that matters: “The bigger the better”—bigger resumes, that is. If you thought dating apps could not get more brutally superficial then you haven’t heard of The League—a dating app catered to students and graduates of elite universities and high–powered professionals. What do all of these students, finance bros, and CEOs have in common? Their big, big … resumes. And the app’s tagline, you ask? “Have you been told that your standards are too high? Keep them that way.”

While Tinder, Hinge, and Bumble occupy the largest share of the online dating market, The League occupies a smaller, more exclusive, corner of the internet. However, despite its reputation, users of the app come from a broader background of schools and jobs rather than just Ivy League schools or Blackstone internships. Nevertheless, the app predictably gained an early reputation of elitism and exclusivity. Whether The League holds up to its own purported standards remains up for debate, but its branding prompts a larger inquiry into a trend of elitism on dating apps and its implications for class divides that shape the dating landscape both in college and beyond.

Since The League’s 2014 launch, the market for online dating platforms has expanded, for better or for worse, but the app’s increased traction from recent advertisements brings it to the center of ongoing cultural debates about institutions of exclusivity and meritocracies. In 2015, CEO and founder Amanda Bradford set out to dispel the platform’s reputation of elitism, describing their unique mission as “promot[ing] higher education, encourag[ing] career–ambition and, most importantly, cultivat[ing] the desire for an egalitarian relationship in both sexes.”

Fascinatingly, it is perhaps more often female–identifying users on dating apps who are more selective with their potential matches. Yet, are gender–based norms and imbalances truly subverted by this particular brand of selectivity? The app instead seems to select a largely monolithic crew of matches while other potential applicants choose to exclude themselves before even applying.

Let me set the scene for you: you are setting up a profile for The League. You are now faced with THE question: “What are your educational dating standards: ‘none,’ ‘selective,’ or ‘highly selective.’” You’re a Penn student, so obviously you pick “highly selective”—you only want the crème de la crème. Next thing you know the app is asking you to connect your LinkedIn profile to verify your academic and professional credentials. You cannot wait for your potential matches to see your very important Morgan Stanley internship listed on your profile—did I mention they list your recent and past jobs on your profile right under your photos—let’s all cross our fingers and hope we do not match with our old coworkers. Now that you have gone through the painstaking process of bragging about your achievements on your profile—an excruciatingly difficult task for Penn students, obviously—you expect your profile to be successfully complete. But wait, what is that? You are now prospect number 39,133 on a waitlist of 39,134 people in Philadelphia waiting for their profile to be approved—and now before you know it, you’re having traumatic flashbacks to Ivy Day.

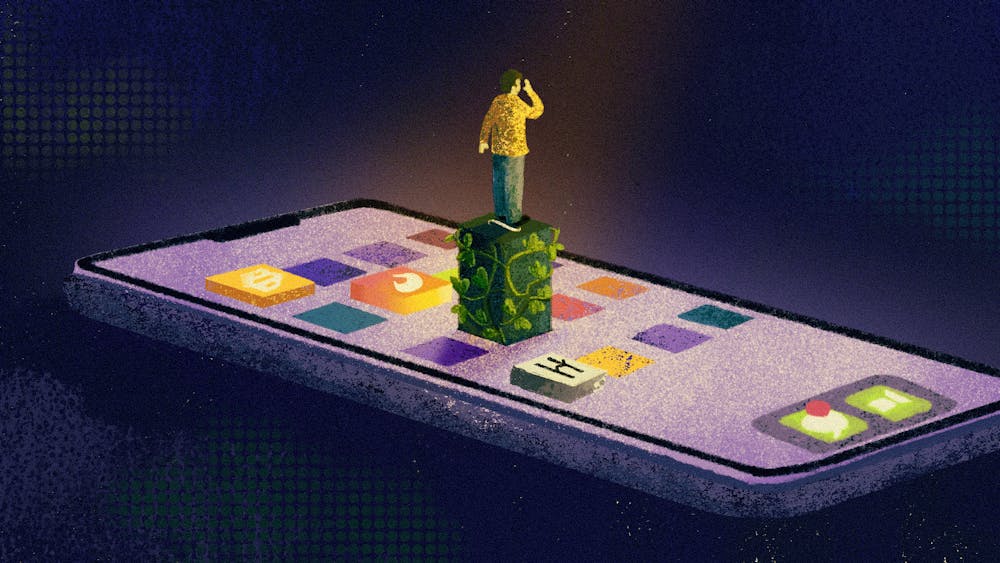

Now, we are all wondering the same thing. “Why does it seem harder to get into The League than it is to get into the actual Ivy League?!” However, unlike the actual Ivy League, the app experience of The League is not actually about what happens or what benefits you reap from being inside the “club”—it is about the delineation of the haves and have–nots—desire for acceptance accumulates exponentially for those who find themselves on the other side of the velvet rope.

If you are curious about how to actually get off the waitlist and have your profile approved, you can either wait out the other 39,134 applicants, or you can join by paying to be a member, effectively skipping the queue. Memberships range anywhere from $100 for a weeklong trial to a one–month VIP membership for a minty $2,499.99. Truly—the similarities between The League admissions and Ivy League admissions are becoming increasingly uncanny—either pay your way forward or wait among the masses.

It is this very fanaticism and desire for belonging that The League capitalizes on. Capturing an audience of students at “elite” schools, the app cultivates another space in which exclusivity is the name of the game. But that is all it is—a perceived, self–reinforcing, air of exclusivity. In reality, you do not actually need to pay $2.5k to participate in a curated cult of elitism—you can DIY it on Hinge, Tinder, or Bumble, swiping right on or liking exclusively “well–educated” or those with “high–power” jobs.

From its early years, Bradford fought back against the media’s framing of the app as a platform for cultivating and perpetuating elitism, decreeing “I’m Not An Elitist, I’m Just An Alpha Female” in a 2015 LinkedIn post. Bradford and her founders instead underscore the app’s intention to cater to women with high educational and professional attainment. Nevertheless, the founder’s intentions and the impact of the app itself seem to diverge from one another in practical application. Certainly, women face social and romantic rejection from partners who are intimidated by their power, influence, and accomplishments. However, it seems that in dating circumstances, particularly online dating, women are more stringent in their standards for their male counterpart’s educational and professional achievements. Perhaps in some way, Bradford desires for women like herself to participate in a selective community in which her options were limited to those men who were adequate prospects and matched her accomplishments—not just someone who wouldn’t be intimidated by her status.

The League isn’t the only dating and social networking platform overtly concerned with status and exclusivity. In the same year that The League was founded, Raya, a dating app culturally known as the celebrity dating app, was released. Formally, Raya is marketed as “a private, membership–based community for people all over the world to connect and collaborate.” Similarly to The League, the application process to Raya requires a stamp of approval. Where The League requires you to connect your LinkedIn to verify your school and job, Raya requires a referral from a current user in addition to a membership fee. Not only does the financial component of both apps impose a class hierarchy with regard to accessibility, the mystery surrounding the referral and acceptance processes generates a mechanism of social acceptance or rejection.

Given that these apps feel harder to get into than an actual Ivy League or Soho House, as a user you would hope that once you are on the other side of the velvet rope you would be met with the crème de la crème of dating prospects. Think again—because that assumption would be wrong. While we would hate to shatter the illusion—it is just that: an illusion. While the exclusivity projected is propped up by entirely arbitrary standards beyond labels and titles, the impact of their presence is entirely real. If as a society we do indeed date for status, these habits reinforce the notion of marriage as an economic proposition. Historically, given the wage gap and gendered relationship expectations, it is the experience of women to be concerned with the economic stability or lack thereof provided by potential male partners.

According to 2023 data from the Pew Research Center, 48% of Americans report that most men married to women would prefer to earn more than their wife. Alternatively, women report a split of opinions; between 26% want to earn the same as their husband, and 22% of women want a husband who earns more than they do. However, only 7% of American women report wanting to earn more than their spouse. These statistics coupled with dating app trends reveal that while men are less focused on the earning potential and accolades of women, specifically when those respective traits are fewer than their own, in contrast, women’s standards are rising. Women in opposite–sex relationships are increasingly stringent with their dating preferences with particular regard to status, education, and professional attainment.

The League’s Bradford continues to defend these so–called “alpha female” desires, arguing that a romantic prospect’s education or job reflects certain qualities of motivation, dedication, and ambition. In the past year, their recent advertisements promise to help you find your “goalmate” or aid you in achieving “goal digger” status, aiming to expand its audience and further deconstruct the app’s reputation for exclusivity. However, the very fact that we associate certain job titles, college degrees, or goal attainment as being entirely meritocratic reflections of one’s hard work and inherent talents is a reinforcing loop of elitism and exclusivity perpetuated by centuries–old institutionalized networks of privilege and access.

I mean, let’s be honest—nepotism might as well have been Merriam–Webster’s word of the year. Reputation by association wields incredible influence—think legacy admissions and Hollywood nepo–babies—you don’t always need to have the skills or ambition to get your foot in the door, you just need to have the name and the network. Ultimately, The League’s insistent denials of elitism allegations are in vain—their reputation has been firmly cemented as that of exclusivity and any denials or efforts to combat this perception will effectively alienate their existing users or degrade the “quality” of their match pool.

Amidst our interrogations of meritocracy and elitism, one quandary remains, why do we collectively feel beholden to the allure of exclusivity and the elusive stamp of approval associated with these “elite” spaces—whether it be The League, Raya, or even the Ivy League itself? The pursuit of prestige consumes our academic lives, our social lives, and now our dating lives. We are beholden to the illusion that there is something better out there for us—some new title or accolade to call our own, a hotter partner, or a bigger salary. The finish line is ever–changing, and these platforms and institutions thrive off our addiction to participating in or achieving the next best thing. Knowing this, when those feelings of inadequacy creep up in the classroom or —find solace in this sentiment—it’s not you, it’s the system.