The poetics of hip hop have long been Benny the Butcher’s instrument of choice. As part of rap collective Griselda, Benny the Butcher is one of the few artists to represent the songwriting acumen and narrative grit at the intersection of lyrical and coke rap—a blend of skill and realism that has escaped his contemporaries across a number of genres. He first garnered critical acclaim on the hip hop scene with albums like Tana Talk 3, The Plugs I Met, and his previous project Tana Talk 4, which was released two years ago.

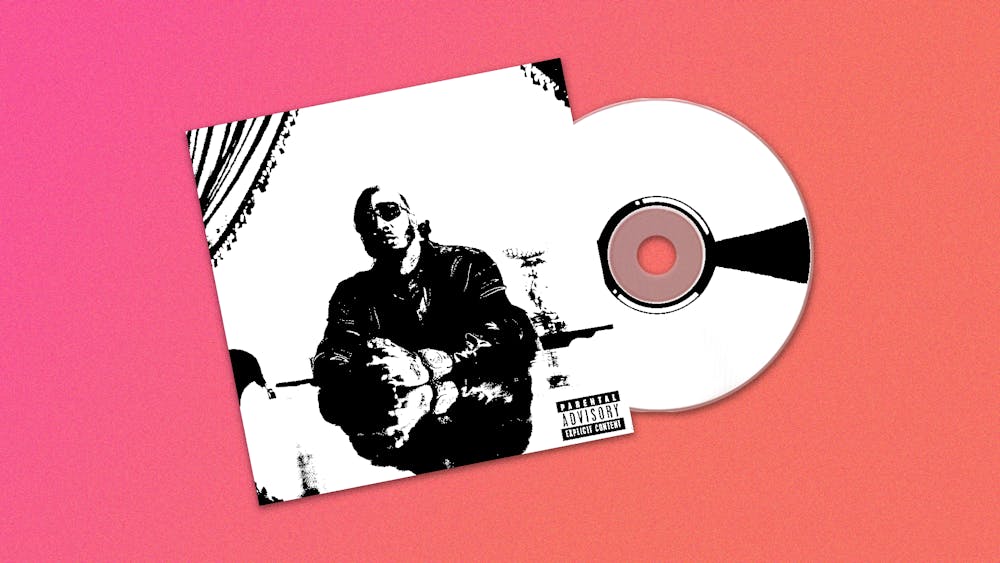

Benny the Butcher’s January 26th release Everybody Can’t Go only further establishes that the rapper is writing and performing at his prime, weaving intricate detail and narrative with persuasive cadence and flow. The twelve–track–long project stays tight like his previous works, but also sees thematic expansions within songs.

The track “TMVTL” is a prime example, as Benny takes on the role of a narrator careening through three distinct stories. The first begins with a former kingpin in jail for presumed gang or drug–related crimes, known as the Prince. Jasmine Dickens is the correctional officer who is assigned to the Prince’s dorm, and, through the Prince’s charm, the two start a secret relationship. Benny alludes to the fact that Prince is more than just enamored by the young lady—his sights are set higher: she is a ticket to the outside world. She is soon smuggling contraband into the prison for him. “He sent that money home, so he meet with Jasmine to re-up again,” Benny writes. When she tries to quit, he threatens to frame her for the illegal activity. He “stuck to his word” by testifying and framing Dickens, and is released from jail early.

The next story navigates similarly uneasy waters, as Benny first paints a rich image of two half–brothers from the same neighborhood, their differences, and the progression of their lives and careers. In adulthood both begin relationships, unaware that they are with the same woman. When she ends up pregnant, the older of the two finds out that the baby is not his, but instead is his brother’s. After the baby is born, he murders both the child and his half–brother.

In the final story, Benny hints that he is speaking about his own life and the time an attempt was made at his life in Houston in 2020. He reveals that his, or rather the unnamed rapper’s, sciatic nerve was “severed” from the ambush, leaving him on prescription painkillers. However, he stays patient. When the attacker is “finally sent to jail” (though the rapper himself never cooperated with police), he has the word BSF (a reference to Benny’s own Black Soprano Family) carved on the man’s face with a dirty nail. All three stories are relayed in four minutes and three seconds, demonstrating the rapper’s technical command of storytelling. In many ways, the track calls back to tracks such as Dave’s “Lesley (feat. Ruelle)” that intertwine reality and fiction to communicate greater themes.

Other high points on the album include “One Foot In (with Stove God Cooks),” a fun and upbeat song that finds its charm in high tempo beats and a catchy hook. The song also reveals Benny’s split obligations between his past life as a drug kingpin and his music career, as well as his decision to make music the dominant force in his life. “Buffalo Kitchen Club (with Armani Caesar)” is another strong performance, as Benny’s collaboration with Caesar comes off natural and well-written.

“How to Rap” is yet another top track, and a clear example of Benny’s willingness to deal with themes beyond dealing. It walks through the progression of the rapper’s career to his eventual commercial success. “Long I was in dark studios, that was the price of it,” he writes. The song is an ode to his dedication to his craft; he remarks on the labels who flew him out to propose deals, “low–balling” him. They “kinda still doubt if they can market you,” he explains. “Turn it down and show 'em that your number was inarguable/ And when they double back, charge 'em triple what they offered you.”

“Everybody Can’t Go” cements Benny the Butcher as one of the best in his lane. It begs the question—why are his talents seldom mentioned when music critics and the public discuss the best songwriters of today? If storytelling and songwriting are the skills in question, Benny has them close to mastered. Hip-hop or otherwise, Benny is outwriting much of his competition, and it is time he is properly appreciated through this lens.